Is PM Modi's Ayushman Bharat too ambitious to succeed?

Inside India's health care fix: Fifteen months after Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Ayushman Bharat health scheme, stakeholders have mixed views

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer PawarOn a humid afternoon last summer, Tasneem Sayed made her way to a student’s shanty in Kishanganj in northern Bihar, bordering West Bengal. The 26-year-old taught English and mathematics to Class 5 students while pursuing her BA alongside. “I returned home after tuitions that day and suddenly got high fever. I was totally fine until then,” she says, shrugging her slender shoulders.

When the fever didn’t subside, her father, a farmer, took her to the local hospital where she was diagnosed with jaundice. A sonography further revealed that she had a tumour, the size of two tennis balls, in her liver. “We were devastated when the doctors told us it was cancerous,” says Tasneem, whose identity has been changed on request.

On the doctor’s suggestion, Tasneem travelled to Mumbai for treatment at the Tata Memorial Hospital. Sitting on her bed in the female ward, arms wrapped around her bent legs, Tasneem wears a bubble-gum pink dupatta over her white hospital overalls. Her face is hollow-eyed and pale, but her high cheek bones and sharp nose cut a striking figure. Her surgery was successfully completed a few days ago, says her brother, Amir, who sits by her side.

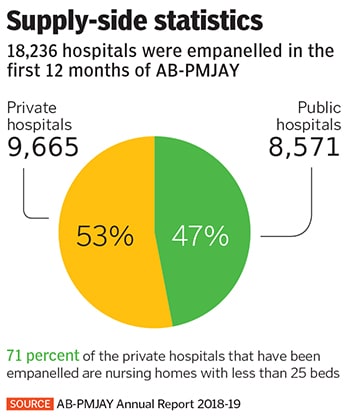

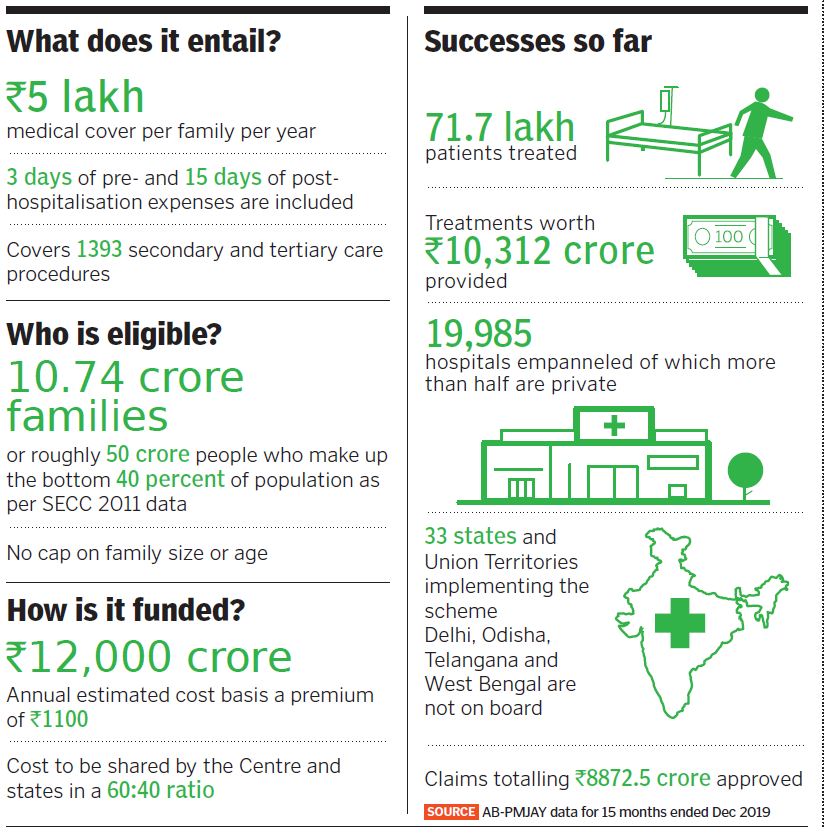

“We received help through Ayushman,” he says measuredly, referring to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s massive government-funded programme that promises health insurance to half a billion people. Dubbed ‘Modicare’, the scheme is built on two pillars: Establishing 150,000 primary health care centres to focus on prevention and early detection of diseases; and providing a cashless cover of ₹5 lakh per family per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation through the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana or PMJAY. Around 10 crore families or 50 crore people who make up the bottom 40 percent of India’s population as per the socioeconomic caste census data (SECC 2011) are eligible.

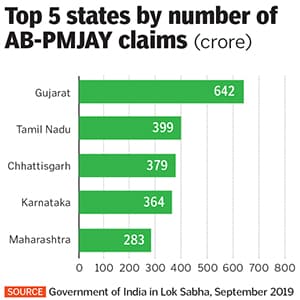

Since its launch in September 2018, six months ahead of the general elections, 71.69 lakh people have benefited from Ayushman Bharat-PMJAY, resulting in cost savings of ₹10,312 crore for them. Claims totalling ₹8,872.5 crore have been approved as of December 2019. “We have gained tremendous momentum in the first year,” says Dr Indu Bhushan, CEO of AB–PMJAY, in an interview at his New Delhi office.

*****

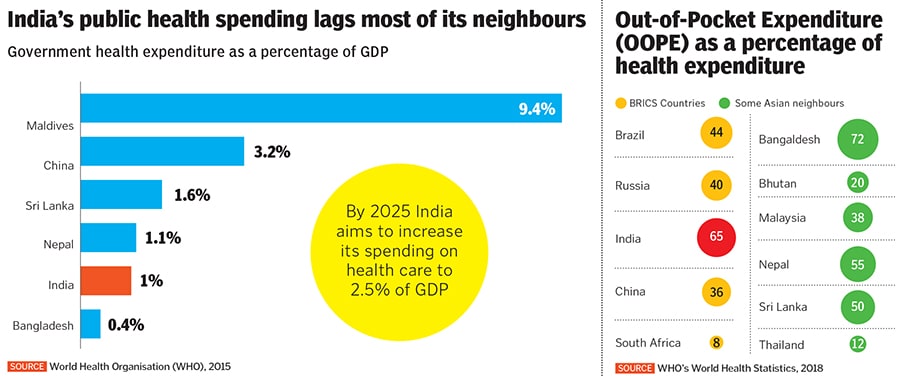

India’s public health record is abysmal. The government spends just about 1 percent of GDP on health care—one of the lowest levels in the world. The US, UK and China spend 8.5 percent, 7.9 percent and 3.2 percent respectively. Neighbouring countries Bhutan and Sri Lanka also score better, spending 2.5 percent and 1.6 percent, according to the World Health Organization.

Poor public spending on health has meant that access to free, quality health care at government-run hospitals is sparse. In search of better care, poor people wager their life’s savings, borrow money from informal lenders and sell assets to pay the bills. Out-of-pocket spending, which accounts for 65 percent of an individual’s health care expenditure in India, pushes 3 to 5 percent of the population into poverty, says the Public Health Foundation of India.

So to provide publicly funded health care to India’s poorest is a “game changer”, says Dr Devi Shetty, founder and chairman, Narayana Hrudayalaya Hospitals.

The premium for providing a ₹5 lakh annual medical cover to each family comes to around ₹1,100 and will cost around ₹12,000 crore in central and state government funds; costs are to be borne by the Centre and states in a 60:40 ratio. When the late Arun Jaitley, as finance minister, had announced the scheme in his 2018 Budget speech, he called it the “world’s largest government-funded health care programme”.

But the challenge lies in its implementation.

AB-PMJAY is an expansion of the central government’s Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) which has an annual medical coverage of ₹30,000, and numerous other state government-funded health insurance schemes that have been running for several years. But these have had a patchy record. Several studies have reported no reduction in out-of-pocket expenses of those insured. One such study looking at hospitalisation cases based on National Sample Survey Office data found that for every 100 cases under various state government-funded health insurance schemes, only three got cashless treatment. This could be due to poor monitoring and improper regulatory regimes, write the authors.

“The government, health care providers and patients will have to go through teething troubles for the next year or so before things start running smoothly,” predicts Shetty, who has allocated 5 to 10 percent of beds at some Narayana Hrudayalaya hospitals for Ayushman Bharat patients.

*****

The Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai charges 30-40 percent less for medical treatments compared to for-profit private hospitals

The Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai charges 30-40 percent less for medical treatments compared to for-profit private hospitalsImage: Mexy xavier

At Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Hospital, Amir pulls out a laminated, pink card from his shirt pocket. It’s Tasneem’s AB-PMJAY card, complete with a photo and fine print on the reverse detailing the services that can be availed of. “The government authorities came home to give this to us…. just months before I fell ill,” says Tasneem, smiling feebly.

“I didn’t know what it was at the time, but when we decided to come to Mumbai, I remembered I had read something about free medical treatment at the back of the card, so I got it along,” she says. The card entitles Tasneem to care at any private or public sector hospital empanelled under the scheme. Pre-admission tests as well as all expenses during the hospital stay, including tests, drugs, consumables, post-operative care, and even transportation and food for the patient, are supposed to be covered under AB-PMJAY. So far, the government claims to have issued 11.78 crore cards.

Unlike RSBY, which required individuals to enrol themselves into the scheme at a particular time of the year, AB-PMJAY is an entitlement-based scheme. Cards have either been sent to eligible individuals based on the SECC 2011 data or they can approach an ‘Arogya mitra’ stationed at every empanelled hospital to get a card made on the spot. “This is a considerable difference between the two schemes and one that is less exclusionary for a patient seeking care,” says Dr Indranil Mukhopadhyay, health economist and associate professor at OP Jindal University, in Haryana.

Another difference between the two schemes is that states are given the flexibility to implement AB-PMJAY in the way they like. They can opt for an insurance-based model, deploying an insurance company to handle the claims or they can go with a trust model where the state government handles the claims. Of the 33 states and Union Territories that have taken up the scheme—Delhi, Telangana, Odisha and West Bengal are not yet on board—a handful have opted for a mixed model, combining the best of the insurance and trust models. Some states like Karnataka and Kerala, which had seven and three state health insurance schemes in place respectively, are in the process of subsuming them under AB-PMJAY, says Bhushan. Others like Maharashtra, which runs the Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Jan Arogya Yojana (MPJAY) health insurance scheme (previously known as the Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Arogya Yojana), is implementing AB-PMJAY as a parallel scheme. The former has a medical cover of ₹1.5 lakh. Once that amount is used, then only can patients dip into the additional ₹5 lakh offered under AB-PMJAY.

In Bihar, Tasneem and Amir’s home state, no state health insurance scheme existed prior to AB-PMJAY. “We are lucky,” says 30-year-old Amir. He left Kishanganj a few years ago to settle in Mumbai where he teaches Arabic at a madrassa. It pays him ₹6,000 a month. He rents a room in a chawl in Malad and gives tuitions to supplement his income. “I end up earning a total of ₹10,000 to ₹15,000 a month. Without this,” he says, holding up the pink card, “we would not have come so far.” Tasneem, still hunched over her bed, nods in agreement.

*****

In 2018, the government allocated ₹1,200 crore to the primary health care pillar of Ayushman Bharat and ₹2,000 crore to insurance pillar, PMJAY. The following year, the latter was ramped up to ₹6,400 crore.

“This is far below what is needed to deliver what the government claims,” says Mukhopadhyay. If, he reasons, you have 2.7 crore hospitalisation cases every year (5.4 hospitalisations per 100 people enrolled, assuming 50 crore people are covered)—in the first 12 months, 46.5 lakh patients received treatment under AB-PMJAY, but as awareness picks up, more patients will follow—and ₹20,000 is the average package rate, it works out to a total of ₹54,000 crore, at current prices. If 40 percent of the cost is borne by the states, that leaves ₹32,000 crore for the Centre to foot. “The entire budget of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is ₹62,000 crore. So you’re talking about half of that just for PMJAY,” he says. “And mind you, ₹20,000 is far below the average package rate, so this is a base level estimate.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)