What happened to disinvestment?

PSU mergers and buybacks make way for strategic sales

.jpg)

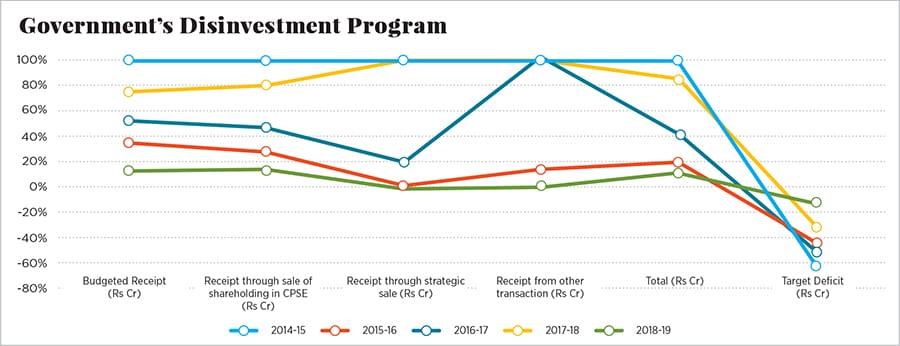

With just a few hours to go for the Union Budget, the government is far from achieving its disinvestment targets for the current financial year. In fact, the only time the Narendra Modi-led NDA government has met and exceeded its target in its tenure was in the previous year (2017-18), when it managed to raise Rs 1 lakh crore as against the budgeted expectation of Rs 72,500 crore. This was achieved by listing insurance companies, mergers of public sector companies, CPSE exchange traded funds (ETFs) and numerous buybacks.

Previous governments hadn’t done much better, overshooting targets just four time since 1991. And in at least four other instances, the UPA government shied away from fixing a target.

During the current year, the government has managed to raise only Rs 35,532.66 crore. The money has been raised mainly through Bharat 22- ETF and CPSE-ETF buy and a few buybacks. The government offers a pool of shares of PSU companies, which are open for buyers to trade in. It recently announced that it would sell its stake in Rural Electrification Corp Ltd to Power Finance Corp, although the transaction is yet to be officially recorded. Even after accounting for that deal, the government still needs a big shot in the arm to reach closer to its target of Rs 80,000 crore.

The way the NDA government has been raising capital through the disinvestment process puts a question mark on whether their strategy truly aligns with the spirit of disinvestment; is it merely a way to shore up capital by forcing PSUs to buy back shares?

Over the last three years, the government has heavily depended on buybacks to fill its coffers and meet fiscal deficit targets. It has found it difficult to raise capital through the strategic sale of assets. Over the years, the government has pinned its hopes on the sale of debt-laden Air India Ltd, helicopter business Pawan Hans Ltd among others, which have not yielded positive results yet. To add to their woes, the government was unable to launch any big-bang initial public share sale program during the year. It had to make do with the likes of RITES Ltd, IRCON Ltd, GRSE Ltd, which collectively managed to raise Rs 1,269.4 crore.

A higher receipt from the disinvestment department is crucial, as the goods and services tax (GST) revenue collections have been below expectations. Between April to November 2018, the government has managed to raise the central GST of Rs 2,97,295 crore against a target of Rs 6,03,900 crore. According to PIB data, gross GST for April to date stands at Rs 8.71 lakh crore as against the full year budgeted target of Rs 12.9 lakh crore.

Consequently, the government is expected to miss the fiscal deficit target of 3.3 percent. Allowing the private sector to pump capital into ailing PSUs will, of course, go some way in turning around these entities even as it provides the government with funds to bankroll welfare programs.

“Disinvestment in India is not happening in the form of privatisation of companies, but as a transfer of resources to the government to raise capital in various ways. Most of the money has been raised by either buybacks or merger of PSUs, or a sale to Life Insurance Corporation (LIC),” says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings Ltd.

Sabnavis adds that the government has no earnestness to give up control in most PSUs and hence they are resorting to transferring shares. “Also, they have been unable to raise capital through strategic sales because most of these entities that are on sale are loss-making units,” adds Sabnavis.

X