How Etihad will Digest Jet

Abu Dhabi-based Etihad has a unique airline-cum-airport strategy that is likely to change the way Jet operates. It promises to be an interesting partnership

Etihad Airways’s Australian CEO James Hogan doesn’t have to think too hard about what to say. This week, he said: “Etihad will discuss ways to further integrate the two networks and help the airline achieve efficiency, build revenue and reduce costs.”

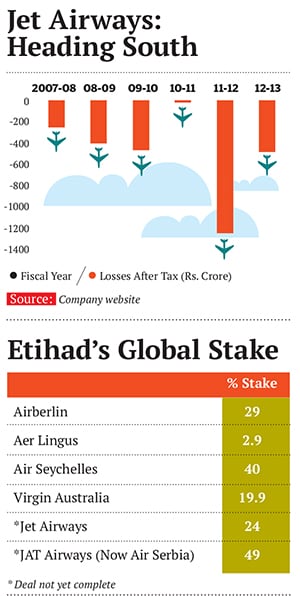

He wasn’t talking about Jet Airways, his most high-profile investment which is likely to be given permission for take-off any time now. He was speaking in Belgrade, where he signed an agreement with the Serbian deputy prime minister to pick up a majority stake in Air Serbia, the latest carrier to come into Etihad’s embrace. When the formalities are complete over the next few months, Etihad will own 49 percent in the loss-making Serbian national carrier.

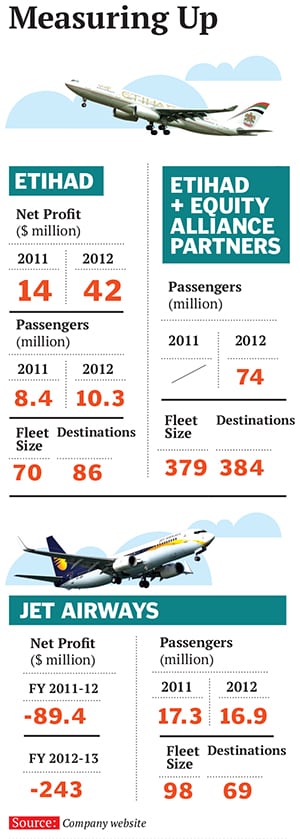

At different times in the past two years, Hogan has made very similar statements about Air Berlin, Aer Lingus, Air Seychelles, Virgin Australia and Jet Airways. Just a decade old, the mid-sized Etihad (70 planes, mostly wide-bodies) has been executing its own version of the ‘string-of-pearls’ strategy around the world, and Jet is only one of them. At the core is not just an equity holding, but a well-crafted airline-cum-airport strategy where Abu Dhabi becomes a crucial hub in this part of the world. Etihad’s expansive web of bilateral agreements with many airlines is built on the reality that airline hubs bring economic prosperity. In many ways, Hogan is thus not only shaping the future of Etihad, but even the future of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi.

In financial terms, Etihad’s investments have just begun to pay off. In 2012, revenue from codeshares with partner airlines was about 19 percent of total revenues. Codeshare and equity partnerships delivered close to $629 million. In terms of scale, though, Etihad is still far behind its older and possibly more glamorous rivals Emirates and Qatar Airways. Yet it is gradually making a mark through its unique model. It already boasts of the largest network for any Middle East carrier, even if less than a third of it is operated with its own metal birds.

Rebuilding Jet

Hogan’s strategy for Jet Airways and India is unlikely to be very different from what he has done around the world. Though the Foreign Investment Promotion Board cleared Etihad’s proposal to pick up a 24 percent stake in Jet, the deal drew much flak for being a sellout. Reality is that Naresh Goyal’s business model was broken and would not have been able to last very long (see: Jet Airways: Heading South). Old Jet soldier Saroj Datta, who has been part of the airline since its inception, minces no words on the situation. “Raising funds was proving to be extremely difficult, and survival would have been tough if not impossible,” he says. Datta had been part of Jet’s senior management for 18 years and has been reading the writing on the wall for years now.

Jet Airways lost its lead position in the Indian market over the past five years after low-cost carriers (LCCs) hit their stride. Goyal was unable to adapt to this shift in market preference for LCCs, but not for want of trying. In fact, he tried too hard and fell flat. From acquiring Air Sahara to fend off Vijay Mallya and Kingfisher, to lobbying fiercely against foreign airline investment, to trying to make his own low-cost airline Jet Konnect click, he tried everything in the book and outside it. Nothing worked. Jet’s debt mounted to $2.1 billion and needed rescuing by a white knight.

Will Etihad save Jet? Addisson Schonland, president of Innovation Analysis Group, an aviation-focussed market research company based in the US, says: “We have seen airlines tied into the Etihad network; [they] all show big improvements once they come under the umbrella. So I would expect to see the same at Jet.” According to Schonland, the challenge will be how the people at Jet deal with this change. Change is coming, he warns, no doubt about it.

Schonland says the folks at Jet will have to realise that their focus is not on Indian competition, but global competition. Etihad and its partners compete against global alliances. Jet will have to “up its game” and that would mean a change of pace for its people. Every alliance is only as good as its weakest partner, and Jet wouldn’t want to be the weak link, he says.

Looking ahead on the changes in Jet’s network, Amber Dubey, partner and head of aviation at KPMG, says Etihad will now have access to 26 Indian cities. A lot of the key decisions will obviously be taken jointly. The new deal will change the nature of international routes for Jet. Most European services are likely to be dropped and the focus will be on connecting to Etihad’s hub in Abu Dhabi. Jet will become more regional, with a heavy focus on providing passenger feeds to Etihad. Ernie Arvai of aviation consulting firm AirInsight says the two airlines will try to provide a more seamless experience for passengers. Aircraft acquisition, seat configurations, and cabin service will be much more integrated.

Arvai says the only question mark is on how deep the alliance will be in operational as well as marketing activities. Given the strong management team at Etihad, they are likely to establish a plan that will slowly integrate the aspects that could result in savings, and aggressively move forward with those. The first focus could be on ground handling at jointly used airports, in which one airline will handle the other’s passengers and baggage without duplication of efforts.

Yet, to really understand what Jet is likely to go through, it might help to look at what Etihad has done with other airlines globally.

The Etihad Way

In some ways, Hogan and his backers in Abu Dhabi are like the Lakshmi Mittals of the airline industry. Just as the steel billionaire fashioned an empire by buying up key, mostly-distressed, steel projects and turning them around to form a larger empire, a big part of Etihad’s ‘multilateral’ strategy is to identify loss-making airlines with access to key source markets. For example, the deal with Air Berlin provided access to the German domestic market—one of the largest in Europe—in the face of bilateral restrictions. Like Dubai and Qatar, Abu Dhabi too has little to boast about in terms of a home market. The latest deal with Air Serbia allows access to the Balkans.

The second feature of all of Etihad’s tie-ups is the careful nurturing of loyal customers. Hogan has developed a collection of frequent flier programmes (FFPs) from airlines that it has a stake in and plans to weld them into his own. In India, an early step was to pick up half of Jet’s FFP Jet Privilege flyers for $150 million. The ability to earn and burn miles is critical to the creamy layer of airline customers. Etihad also owns 70 percent in Air Berlin’s FFP Topbonus.

The third is increasing efficiency. Though Etihad’s equity tie-ups are still in the early stages, Hogan says they have led to costs going down by over 5 percent last year. This can work in not so conventional ways. For example, Air Berlin was cutting jobs last year, mostly pilots and crew. Half the pilots were transferred to Etihad even as the German carrier cut its fleet and its majority shareholder prepared for international expansion. The Etihad group has been able to renegotiate deals with suppliers. The first meeting of all the CEOs in the group was held in May this year.

The airline industry is notorious for losing money hand over fist. Alliances, tie-ups and sharing of resources have been standard practice around the world for decades. Code-sharing is a tool used in dozens of variations by airlines to fill their seats. In many ways, Etihad is likely to succeed because unlike open-ended alliances, it has equity and control. The large alliances (like Star or Oneworld) are co-operative. The Etihad version comes with a lot more power because equity means enforcing rather than persuading traffic to board Etihad, says Schonland. He is convinced the model is scalable as long as it continues to be financially strong and can afford investing in each deal.

Speaking on the sidelines of the IATA annual general meeting in Cape Town earlier this year, Hogan had shared his global plans with the media. He is convinced that Etihad will grow organically. Real acceleration for the airline begins in 2015-16, when it starts taking deliveries of big birds like the A380 and Boeing 787. In his mind, the day is not far when Air Berlin could fly directly to India. This seems to be wishful thinking, considering the opposition there was to the Jet-Etihad tie-up. Amber Dubey, who has been advising both the Ministry of Civil Aviation and airlines, is among the few opinion leaders bullish on the deal. He says it will help the Indian civil aviation industry by enhancing capacity, increasing competition and bringing down airfares. He is all for freeing the airline business from FDI restrictions. “Let there be as many foreign airlines operating in India through their 100 percent subsidiaries or by buying into Indian carriers. India will only gain,” he says.

So will Etihad.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)