Titan: The Golden Cage

Bhaskar Bhat spent eight years cleaning up the legacy of the 1990s at Titan Industries. Now his new growth plan will need to convince a sceptical board

July-August is a time for special discounts on Usman Road, the main jewelry market in Chennai. Winding queues stretch outside the dozens of shops — some as small as 100 sq. ft. and some as big as 12,000 sq.ft — as women from all over South India converge to buy gold and diamond jewelry well in advance for the marriage season several months later. A flyover keeps the shoppers free from traffic these days.

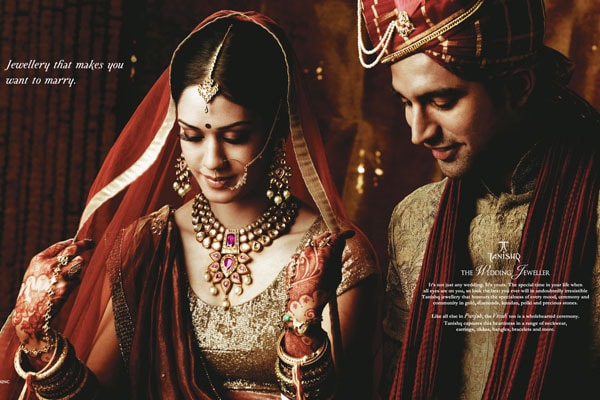

Store space on this road is coveted as new jewelers crop up each year and home-grown stores such as GRT, Prince and Lalitha keep expanding in all directions. This year, there is a new addition to this buzz: A brand new 20,000 square feet showroom from Tanishq which ushered in the branded jewelry culture 15 years ago in a country long used to family goldsmiths.

As one of the biggest jewelry shops on this famous road, the new Tanishq outlet may well mark a shifting preference in the conservative Chennai market towards big format stores.

It is also a take-off point for the new game plan of 55-year-old Bhaskar Bhat, managing director of watches and jewelry maker, Titan Industries. Tanishq has evolved into the Bangalore-based company’s premier business but is now under threat from new competitors with deep pockets. It needs to scale up quickly and gain a substantial market share to avoid being dislodged by them. The mega shop in Chennai, five times the size of a typical Tanishq outlet, will give important clues as to how Bhat can achieve that.

But even to come to this point, Bhat and his team have had to work hard for nearly a decade. Tanishq had once come dangerously close to being nixed as a brand by Titan’s board and the company itself was battling a debt-ridden balance sheet after a failed international expansion. Low profit margins denied him the cash to invest in growth and convincing the board of new plans wasn’t easy.

From there to 2009-10, when Titan Industries crossed a billion dollars in sales with a 23 percent revenue increase and a 39 percent net profit increase, Bhat has come a long way.