Banking on the LIC lifeline

IDBI Bank joins the likes of PNB and Canara Bank, among other PSBs, in the insurance behemoth's portfolio. Will this collective stress hurt policyholders?

LIC may infuse nearly ₹13,000 crore into IDBI Bank for a 40 percent stake

LIC may infuse nearly ₹13,000 crore into IDBI Bank for a 40 percent stake

Image: Shreyas Mohite

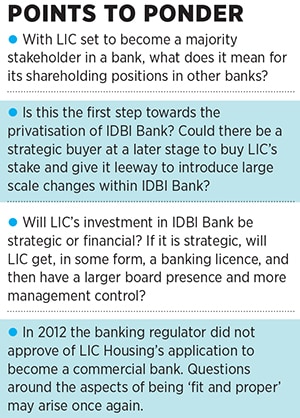

When the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (Irdai) met on June 30 at its headquarters in Hyderabad to discuss a possible move by the Life Insurance of India (LIC) to raise its stake in one of the country’s weakest banks, IDBI Bank, the contours of the meeting and its decisions, were quite evident from beforehand. Under its recently appointed chairman Subhash Chandra Khuntia, Irdai allowed LIC to hold more than 15 percent stake in a particular company, granting an exemption in the regulatory rules for insurance companies. (An approval from the LIC and IDBI Bank boards is awaited.)

This paved the way for LIC to bail out yet another public sector company, adding to a long list of disinvestments that include Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd, General Insurance Company, New India Assurance and Indian Oil Corporation in 2017 and 2018, besides buying stakes in Bhel, ONGC and NTPC earlier. Although these investments have been officially announced, LIC has not disclosed their rationale or impact.

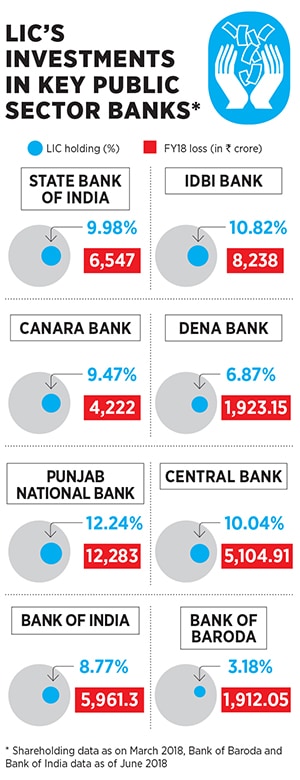

LIC may now decide to infuse capital of nearly ₹13,000 crore into IDBI Bank for a 40 percent stake, with the government’s stake decreasing proportionately. Currently, LIC holds 10.82 percent stake in the bank, while the government holds 80.96 percent; other institutions and the public hold the rest. LIC’s total assets are ₹25 lakh crore (about $385 billion), with a life fund of about ₹23 lakh crore, as of FY17.

Just nine days before the June 30 meeting, the government, through officials in the ministry of finance, had suggested that a decision from LIC to pick up additional stake in IDBI Bank would lie “with independent boards” of both organisations. So, what then was the tearing hurry for LIC to hike its stake in a loss-making bank?

In a family of capital-guzzling public sector banks (PSBs), IDBI Bank received the highest recapitalisation from the government, of ₹12,471 crore, in FY18. What is worrying are its gross non-performing assets (NPAs) of ₹55,588 crore, which form 28 percent of its total advances as on FY18. The bank has reported a net loss for the last three years—widening with each year—to touch ₹8,238 crore on March 31, 2018. LIC’s increased stake in it could mean the government will not need to provide additional recapitalisation, at least for this year.

Appealing against the move that might make LIC the promoter of IDBI Bank, the All India LIC Employees Federation has written to its chairman VK Sharma. “It [IDBI Bank] will need significant amount of capital to clean up its books and maintain minimum levels of regulatory capital. Given the precarious situation of NPA in IDBI Bank and the intention of LIC to substantially raise its stake in the said bank, there is contagion risk on the policyholders’ precious savings, which will grossly impact the capability of LIC to serve its policyholders,” the letter says.

“Dumping IDBI Bank on LIC will not be of help to anyone. It is just going to postpone a problem. LIC will have to pay for this in the long term,” says Rajesh Kumar, general secretary of the federation. He argues that investment decisions gone wrong will finally impact the books of the corporation and, in this case, the valuation surplus for LIC. The insurer’s valuation surplus—the money available for distribution to policyholders (as a bonus) after paying expenses and taxes—has fallen by 11.87 percent to ₹44,006.67 crore in FY17, compared to the previous year.

To ensure proper governance, if a bank or an investor is keen to buy another company, it is usual practice to draw up a proposal and present it to the company’s board, regulators and shareholders. However, it did not happen in this case. “A proposal could have been made to the policyholders. They provide the funds, and the investments are made out of life funds managed by LIC,” says a financial advisor on condition of anonymity. “We have a peculiar situation, where the shareholder has only subscribed ₹200 crore by way of capital, and all the reserves that are a part of net worth belong to the policyholders.”

Insurance companies make investments to generate returns and increase its actuarial surplus every year. This ensures that their liabilities—claims made by policyholders—are always met. However, in the case of LIC, which was formed in 1956 by nationalising around 245 companies and consolidated into a single entity by an Act of Parliament, its policies are sovereign guaranteed.

Following the collapse of state-run mutual fund US-64 in 2001, policyholders were worried that LIC would go the same way. “Concerns regarding the solvency of LIC were being raised since it focussed largely on selling products that guaranteed [assured] returns,” the financial advisor says. In 2003, the LIC board appointed Deloitte India to conduct a management audit, focusing on assessing financial viability, investment management and capital requirement for the organisation. While solvency fears of the LIC were dispelled, it was found to be needing capital.

It remains imperative for LIC to invest prudently and manage returns well. But “the benchmark performance of its investment portfolio is not publicly available and therefore there is no basis available to examine the robustness of its investment decisions. Very often LIC has made its funds available for federal and state government projects and public-sector entities,” the advisor adds.

IDBI Bank’s genesis was in 1964 as a development financial institution called IDBI, whose ownership was transferred from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to the government in 1976. In 1992, when new banks were created, IDBI applied to diversify into commercial banking, and, between 2003 and 2008, became a corporate entity operating under the Companies Act.

What has hurt IDBI Bank the most in recent years is its institutional book, which was largely focussed on infrastructure. “If it was a bank in the first place, the proportion of lending towards infrastructure would have been smaller. The other benefits of becoming a bank—building deposits, a branch network, a retail franchise or becoming a diversified lender—came later,” says Udit Kariwala, associate director (financial institutions), India Ratings & Research, part of the Fitch Group. He believes that in the new set-up, IDBI Bank’s management may not be from LIC; the insurer could, instead, place a nominee on the bank’s board and not directly manage daily operations.

The first step would be to start cleaning up the bank’s books, which, analysts say, could take more than six to seven quarters. “The bank will need to clean up its balance sheet further by writing off a few more large bad loans accounts,” says Asutosh Mishra, senior research analyst, Reliance Securities. “One option could be to transfer these loans into an asset reconstruction company or alternate investment funds.”

However, LIC’s concerns go well beyond IDBI Bank: It owns stakes in 21 PSBs, most of which are listed under prompt corrective action, which is a monitoring and control mechanism introduced by the RBI to take remedial action against weak banks. Some of these banks have shown a sharp drop in their stock prices in the past four years, thereby affecting LIC’s profitability in these investments.

The bad news is that for PSBs, slippages towards bad loans are nowhere close to an end. Kariwala of India Ratings says the total expected corporate slippages over the next four quarters (July 2018 onwards) could be in the range of ₹1.2 to 1.4 lakh crore, that too only relating to the corporate book. Some more slippages could come from the small and medium enterprises and retail books.

An independent Fitch study shows that nearly half of India’s PSBs are at a risk of breaching their minimum capital triggers, indicating the need for further recapitalisation.

LIC has a 12.24 percent stake in Punjab National Bank (PNB), which is reeling from a ₹14,357-crore fraud. Analysts say that a sharp rise in stressed assets and impending provisions (on gratuity, investment depreciation) will be concerns going ahead in FY19. “PNB could take some more time to come out of its troubles. The government will attempt to do its best to turn things around,” says Mishra of Reliance Securities.

In the case of Canara Bank, where LIC has a 9.47 percent stake, it will need to make changes in their business strategies. In FY18, it reported a loss of ₹4,222 crore, against a profit of ₹1,122 crore in FY17, hurt by higher provisions for bad loans. The bank’s gross NPAs were not too far behind IDBI Bank’s, at ₹47,468 crore by March-end. Canara Bank has now approved a fund raising plan for ₹7,000 crore for the current financial year, to fund credit growth.

According to a Motilal Oswal post-Q4FY14 earnings report, the net stress on the books remains high, and the bank will face high credit costs that would keep returns subdued. “Given weak operating profitability, we would wait and watch developments in asset quality,” wrote Anirvan Sarkar of Motilal Oswal, in a note to clients in May.

But even while other banks struggle, the attention for now will be on IDBI Bank. Ashvin Parekh, managing partner of Ashvin Parekh Advisory Services, says, “Time will tell whether the investment made by LIC is a good one. The answer lies in the price that LIC will be required to pay for the equity.”

As of now, LIC has not disclosed the valuations, or the assumptions made, towards the price. The requirement is for an independent body or a judicial system, like the Comptroller and Auditor General, to examine the investments made by LIC, or where blatant exceptions have been provided. This would make the LIC board and, in turn, the government, more accountable for their decisions. Till then, one can only hope that LIC takes on the role of an active fund manager for its investments.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)