American Chop Suey

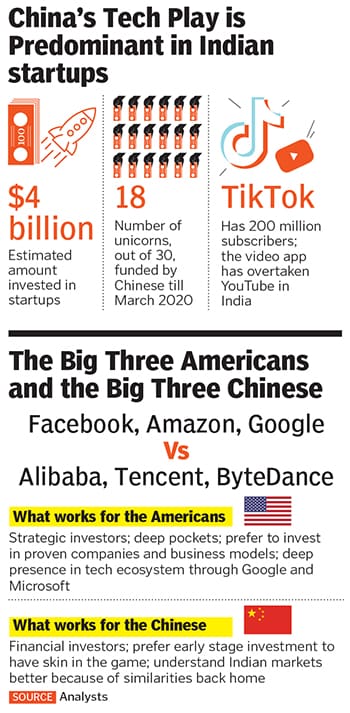

Though American Big Tech will have deeper strategic investments over the next few years, Chinese money is the fuel for the Indian startup ecosystem. Can Covid-19 roll that back?

Image: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Image: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

September 19, 1994. The day Alibaba Group went public on the New York Stock Exchange—a $21.8 billion IPO was bigger than Facebook’s $16 billion in 2012, making it the biggest opening offer in US stock market history—founder Jack Ma made a gushing confession about his American hero Forrest Gump. “Well, I got my story, my dream from America,” Ma told CNBC. The hero, the maverick entrepreneur continued, I had is Forrest Gump. The Academy Award-winning classic was released a few months earlier, with Tom Hanks in the lead role. “I really like that guy. Every time I’m frustrated, I watch the movie,” Ma professed. “I watched the movie again, telling me that no matter whatever changed, you are you.”

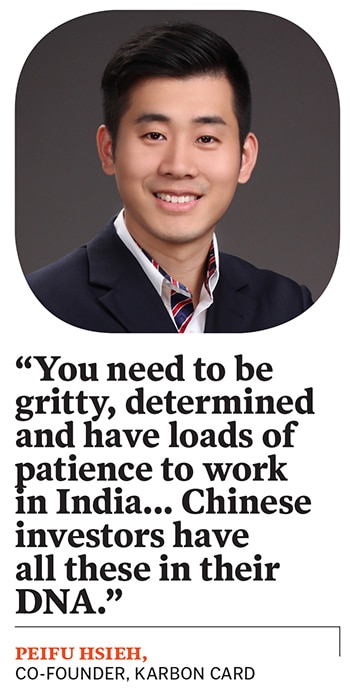

April, 2020. Back in India, Peifu Hsieh, a Chinese venture capitalist (VC)-turned-entrepreneur who co-founded fintech startup Karbon Card, based out of Bengaluru and Shanghai last November, had his share of American dream. Peifu worked with American VC fund Kleiner Perkins for a few years before returning to India in 2017.

Ma’s American hero is also Peifu’s. Rating Forrest Gump as one of his favourite movies, Peifu parrots Gump’s famous one-liner: Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get. The 40-year-old smiles, takes a swig of filter coffee and digs into a dosa. “Dosa is the most value-for-money for breakfast,” he effuses on a WhatsApp video call, explaining his venture. Karbon Card issues credit cards to startup founders; the fledgling venture raised $2 million in seed funding from a clutch of angel investors, including Kunal Shah, founder of fintech firm Cred, and Pine Labs CEO Amrish Rau, in March. “India has fundamentally changed over the last few years,” he says, commenting on the recent Facebook-Jio deal. “US investors will now find India more appealing.”

In April, India unveiled what might turn out to be a box of bitter chocolates for Chinese investors. The new FDI (foreign direct investment) rule makes prior approval of government mandatory for foreign investments from countries that share a border with India. That China is responsible for letting loose the coronavirus has resulted in several countries, India included, seeing justification in attempting to exclude it from global trade dynamics. There’s also the ostensible threat of opportunistic takeovers of Indian companies whose valuations might have taken a beating due to Covid-19.

The fear is widespread. Europe had already pressed the alarm button after seeing what happened in 2008 when Chinese buyers took advantage of the global financial crisis to take controlling stakes in strategic infrastructure and mining companies. Peifu, though, contends such fear are misplaced. India will continue to be a hunting ground for anybody looking for the next big bet.

The big bet from American Big Tech—Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon—on India comes at a time when a new geopolitical and financial landscape is taking shape in a post-Covid world. “The American big boys can give a tough fight to Chinese heavyweights in India,” reckons Vikram Gupta, founder of IvyCap Ventures. The reasons are not too hard to fathom. India is likely to be relatively better placed once the world comes out of the battering of the pandemic. Though the initial big bets from the US and Japanese investors are going to be placed on established companies and startups with proven business models, over the next few years, they will trickle down to deals closed at the level of early startups.

For Chinese funds, the new FDI rule adds an extra hurdle. “It might be frustrating for them and prolong the process of deal closure,” adds Gupta. In all, it looks like its advantage America as it looks to place more bets outside China, Gupta contends.

Yet, the new law on paper may do little to alter the ground reality of Chinese money fuelling the Indian startup ecosystem. Reason: The fundamental difference in the nature and mindset of Chinese and American investors. Mahendra Swarup, founder of Venture Gurukool, explains. Americans, he underlines, are strategic investors. They will invest in companies and ventures that are either established or have a sizeable market share. The Chinese, on the other hand, are financial investors, who spot early opportunities and build the entire ecosystem.

Out of 30 unicorns—ones with a valuation of $1 billion and above—18 are heavily backed by Chinese funds (see box). Though America has an upper hand when it comes to FDI in India—$28.3 billion versus $6.2 billion by Chinese by the end of last year—the game shifts heavily in favour of the investors from dragon land when it comes to startups. The Chinese, Swarup underscores, have a better understanding of Indian conditions. As for takeover concerns and apprehensions about the Chinese intention, Swarup wants critics to look at the track record of how investors across the Great Wall have behaved in India. “Alibaba could have stopped Paytm from getting SoftBank (from Japan) on board. But it never happened,” he says. Though the government might be justified in coming up with the new rules, there is no reason to be apprehensive about Chinese investors. “They have built the startup ecosystem in the country. The Chinese handsets players, unlike Apple, have invested heavily in India,” he adds.

Back in Shanghai, Edward Tse contends that Chinese investors stand a better chance of making it big in India. “India is a major potential market,” says the founder of Gao Feng Advisory Company, a global strategy and management consulting firm. Expressing concern about the global negative sentiments against China, and attributing it to largely due to political posturing in the US and Western media, Edward finds the backlash unjustified. “China is not a bad guy,” he says. Though the perception might have percolated down to India, Edward is optimistic that the sentiments will improve in the country, which is likely to recover quicker than others from the pandemic. Stressing that there is a need to separate government posturing from corporate behaviour, Edward contends that American investors would still be actively looking for investment. What makes Chinese better placed in India, he lets on, is a high risk-taking appetite. “They bet on 10 early stage ventures in India, and look for one jackpot,” he says. The Indian startup ecosystem, he underlines, is where China was 13 or 15 years back. The Chinese have seen the transformation in their home country and they just are just replicating that success in India. “India will remain a good destination.”

Back in India, Amit Bhandari reckons that new FDI rules won’t choke investments into the startup world. “Mainland Chinese companies are just one of the many pools of capital investing in Indian startups,” says Bhandari, Fellow (Energy and Environment Studies Programme) at Gateway House, a Mumbai-based think tank. There are funds from the US, Europe and Japan as well. Closely scrutinising one pool of capital, he lets on, is not going to destroy Indian startups. The recent $5.7 billion investment from Facebook in these trying times will send the right signal to the investing community that Covid-19 has had little or no impact on India’s digital economy.

In a recent report on Chinese investment in India, Gateway House underlined the inherent threat. “Chinese FDI into India is small at $6.2 billion, but its impact is already outsized, given the increasing penetration of tech in India,” the report points out. The report outlines three reasons for China’s tech dominance in India. First, there are no major Indian venture investors for Indian startups. “China has taken early advantage of this gap,” it highlights, underscoring the point by highlighting how Alibaba’s investment in Paytm in 2015 paid off barely a year later after demonetisation. Paytm, the report stresses, benefited from Alibaba’s superior fintech experience, which it applied to India seamlessly, making it a dominant player.

Second, China provides the patient capital needed to support the Indian startups, which like any other, are loss-making. “The trade-off for market share is worthwhile,” the note points out. Third, for China, the huge Indian market has both retail and strategic value. Therefore, companies like Alibaba and Tencent have different considerations and horizons for their investments. In contrast, Western venture money is mostly through funds like Sequoia and SoftBank.

There’s another segment where China has seen early opportunity in India: Electric mobility. India is the world’s fifth-largest auto market. China’s BYD, the Gateway House report asserts, has been pushing its electric buses in India, with limited success. In traditional autos, which is 99 percent of the market, China is using recognisable, but distressed, global auto brands like Volvo and MG, which it acquired to enter the Indian market. “So far, Chinese automakers have invested $575 million in India,” the research paper highlights, adding that the competition in India is fierce with Indian and Asian automakers like Suzuki, Hyundai and Toyota, even as US automakers withdraw.

The fear of Chinese hostile takeovers in India, and across the world, might be exaggerated. According to a recent report by US-based research firm Rhodium Group, the virus outbreak brought China’s outbound investment to a halt earlier this year. Since 2016, China’s outbound investment has been on a downward trajectory. Outflows dropped precipitously in 2017 and 2018 after Beijing restricted irrational outflows, the report points out. In addition to domestic regulators, Chinese investors also were confronted with greater regulatory and political scrutiny abroad, as economies tightened investment screening regimes due to concerns about China’s compatibility with their democratic market economies. “This slowdown is visible across all available data sources and has changed the narrative of the inevitable rise of China as a global investor,” a Rhodium Group report outlines.

Meanwhile in Gurugram, Haryana, a top Chinese VC explains why India would need more Chinese money over the next few years. “America and Japan,” he says requesting not to be identified, “will become more insular.” Both these countries will look at investing more in their respective homelands to reduce their dependence on China. Add to it the fact that they have been badly battered by the pandemic from which China has started to recover, and India has been doing better than other countries in its fight. “So where is the money going to come from? It’s China,” he says. “They always look for quick money, and would thus bet on known names.”

Peifu, for his part, reckons that stakes are high for both American and Chinese investors, as none can afford to lose the Indian market. Will then life for the Chinese investor and entrepreneur be like a box of chocolates? “Am looking forward to the future,” he signs off, much like the hero in Forrest Gump who used to swear by his mother’s advice: My Mama always said you’ve got to put the past behind you before you can move on.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)