Luxe pop: Luxury goes to small towns

How the aspiration for luxury has travelled well beyond the metros and their cityslickers

Image: Amit Verma

Image: Amit Verma

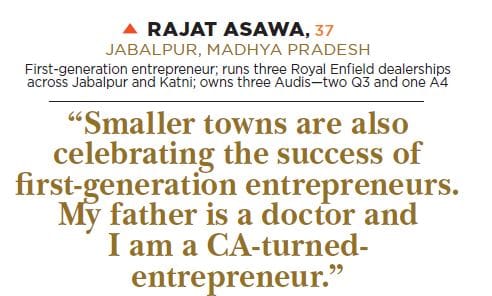

Type JLR on Google and it will direct you to the website of luxury carmaker Jaguar Land Rover. But, as Rajat Asawa would tell you, flashing his air ticket with the acronym on it, JLR is also the abbreviation of choice for airlines flying out of Jabalpur, a tier II city in Madhya Pradesh with a population of roughly 14 lakh. “There is a connect between JLR and Jabalpur,” grins the 37-year-old chartered accountant.

Waiting at the domestic airport in Mumbai for his direct SpiceJet flight to Jabalpur, Asawa rues the lack of more flying options to his hometown, historically overshadowed by the political capital Bhopal and largest city Indore. “There is either SpiceJet or Air India,” he laments, intermittently checking the time on his Rolex Submariner Date. The daily SpiceJet flight departs at 2 pm from Mumbai. Asawa’s crisp white Express shirt, an American brand, and blue Levi’s denims add to his casual look. He’s also sporting a Louis Vuitton belt he’s just picked up in Mumbai.

During the two-hour flight, Asawa lets on how his decision to quit his job at Deloitte in the US eight years back took his doctor-father by surprise. “But he stood by me and encouraged me to live my dream,” recalls the first-generation entrepreneur, who now runs three Royal Enfield showrooms in Jabalpur. “The bestseller in Jabalpur and nearby towns is the Enfield Classic, priced at ₹1.5 lakh,” he offers.

On arrival at Jabalpur, an Audi Q3 is at hand to pick up Asawa. “Welcome to Jabalpur,” he smiles. “JLR will also happen soon.”

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Image: Madhu Kapparath

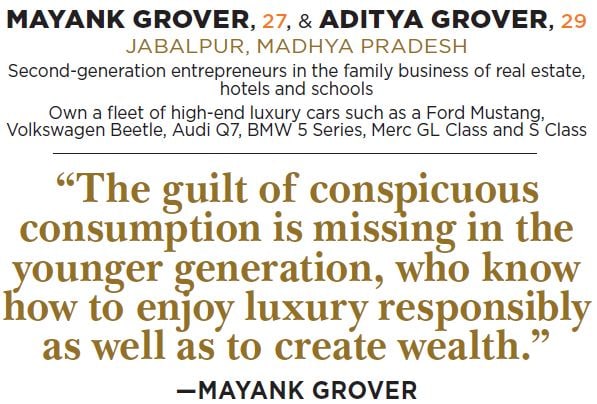

Roughly 15 km from Jabalpur airport towards the heart of the town—a journey punctuated by dilapidated roads, slow traffic and neatly lined up fruit and vegetable stalls on either side of the road—Mayank Grover and his elder brother Aditya are getting ready to visit an under-construction hotel site. The structure is being built by their family-owned real estate firm.

Mayank, 27, wants to take his Ford Mustang while Aditya insists on driving his Audi Q7. The brothers settle for their third luxury car, a Beetle. “We have the biggest fleet of luxury cars in Jabalpur,” says Mayank, “but they have not run even 2,000 km.” While it’s a luxury to have such cars, chips in Aditya, it’s a shame if you can’t drive them regularly.

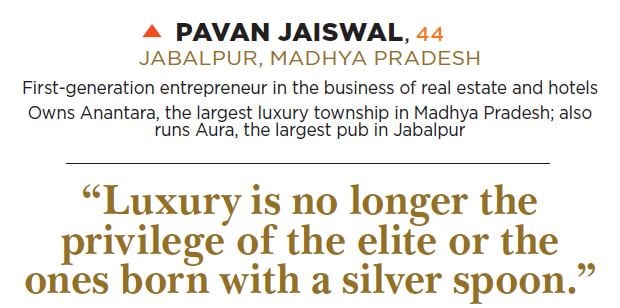

Asawa and the Grovers are not aberrations in Jabalpur, which is fast emerging as the luxury capital of Madhya Pradesh. The sleepy city, which exhibits all traits of a small town, is dreaming big. Anantara, a 72-acre luxurious township where villas are priced between ₹1.75 crore and ₹2.25 crore, is the city’s crowning glory. “All the 110 villas have been sold out,” claims Pavan Jaiswal, owner of the township, who also runs the biggest pub in the city. “The size of the pub would put counterparts in Delhi and Mumbai to shame.”

Luxury, as one finds out, is in full bloom in non-metropolitan India. High-end luxury cars, upscale villas and opulent lifestyle brands are finding ample takers.

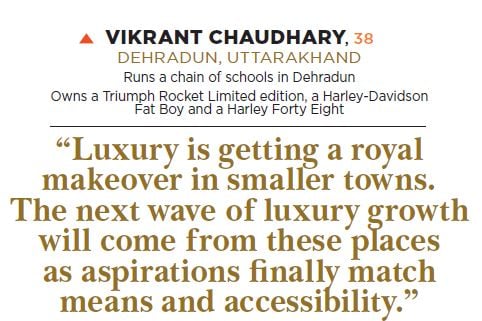

From Jabalpur, let’s move northward to Dehradun in the hill state of Uttarakhand, famous for its residential schools. Vikrant Chaudhary, 38, who runs a chain of schools, is one its new-found luxury champions. He owns a Triumph Rocket Limited edition, a Harley-Davidson Fat Boy and a Harley Forty Eight. The combined value: Over ₹50 lakh. The second generation entrepreneur also boasts a Jaguar, a Porsche and an Audi Q7. “Luxury is getting a royal makeover in smaller towns,” says Chaudhary, who got inspired by Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator to buy a Harley. The next wave of luxury growth, Chaudhary lets on, will come from outside the big cities, as aspirations finally match means and accessibility.

Chaudhary completed his schooling from Dehradun, college from Ramjas College in Delhi, and his MBA from Delhi University. Though there were job offers from private companies, opting for the family business was a logical conclusion for Chaudhary, who was convinced with the potential of Dehradun in terms of growth and prosperity due to infrastructure growth and a real estate boom.

“Wealth has not only been created, it has also passed onto new hands, a new generation, a new mindset,” he avers. Unlike older generations and families with ancestral wealth, the new generation is more liberated in their outlook. “Enjoying the present has gained prominence over saving for the future. A slice of luxury is yearned by all,” he adds.

Young consumers are the ones behind the luxury push in smaller towns and cities. The demographic in luxury, reckons Manoj Adlakha, CEO of American Express Banking (India), is shifting towards a younger population. More people in India are becoming wealthy at an earlier stage and are used to spending money on luxury goods compared to traditionally wealthy groups. This young and dynamic affluent population has increasing awareness of and access to goods and services from around the globe, accelerating their desire for exclusivity. “At American Express, we have seen card acquisition in the next 10 cities grow at 3x the rate of the metros,” he says.

Luxury analysts spot a larger wave sweeping across India: ‘Democratisation’ of luxury. Rapid urbanisation, well-travelled consumers, high disposable incomes, brand consciousness, an emerging class of young, successful entrepreneurs, digital and social media have propelled the growth of luxury brands beyond the big cities.

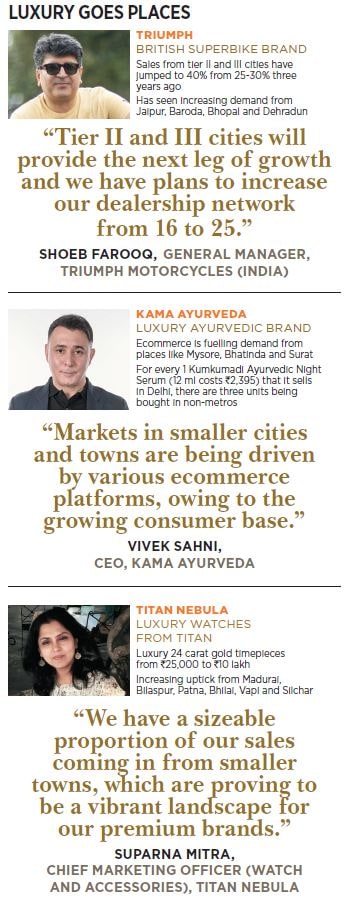

Luxury brands are taking note of the big changes in small towns. Titan Nebula, luxury watches from Titan, has seen an increasing demand for its high-end products—24 carat gold timepieces start from ₹25,000 and go up to ₹10 lakh—from places like Madurai, Bilaspur (Chhattisgarh), Patna, Bhilai, Vapi and Silchar.

“We have a sizeable proportion of our sales from smaller towns,” says Suparna Mitra, chief marketing officer (watch and accessories) at Titan Nebula. These markets have tremendous purchasing power and growth potential, as the aspirations are largely mirroring those of bigger cities. The convergence of tastes, preferences and aspirations between smaller towns and big cities will be an important dictator of future trends for the company. “Smaller cities are proving to be a vibrant landscape for our premium brands,” Mitra adds.

Triumph, the British superbike brand, has seen sales from tier II and III cities jump to 40 percent from 25-30 percent three years back. Over the last five years, it has established its footprint in over 400 towns. “Tier II and III cities will provide the next leg of growth and we have plans to increase our dealership network from 16 to 25,” says Shoeb Farooq, general manager at Triumph Motorcycles (India).

Even luxury ayurvedic brand Kama has seen a steady uptick from smaller towns, thanks largely to the ecommerce boom. “The market in smaller cities is being driven by various ecommerce platforms, owing to the growing consumer base,” says Vivek Sahni, CEO of Kama Ayurveda. For every 1 Kumkumadi Ayurvedic Night Serum (12 ml costs ₹2,395) that Kama sells in Delhi, there are three units being bought at non-metros like Bhatinda.

Online shopping, reckon marketing experts, has opened the floodgates for luxury brands to smaller cities and towns. While a boom in ‘pre-owned’ luxury has made it affordable for millions of aspirational users, online shopping has made it accessible, says Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor, SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. “Luxury brands don’t need to be physically present across the nook and corner of the country.”

Ecommerce major Amazon has seen over 55 percent demand for precious jewellery coming in from tier II and III cities. “In fact, orders from tier III cities such as Belagavi, Mandya, Raigarh, Jamnagar, Thrissur and Eluru have been overwhelming,” says an Amazon India spokesperson. Some of the premium and luxury brands working with Amazon in India are BMW Mini Cooper, Dyson, Leica Camera, Kama Ayurveda, Forrest Essentials, Parcos and UnderArmour.

German luxury major Montblanc, whose writing instruments run up to a few lakh per piece, too realised the power of the online medium early this year. When the Indian arm—a 59:41 joint venture between the Hamburg-headquartered company and Titan—decided to offer its products through ecommerce platform Tata CLiQ Luxury in April, the response was an eye-opener. The first sale came from Kanpur, followed by more orders from Bilaspur (Chhattisgarh), Raipur, Coimbatore, among other non-metros. “The majority of the online sales were coming from cities and towns where we do not have a boutique,” Nicolas Baretzki, CEO of Montblanc International GmbH said. |

Image: Amit Verma

Image: Amit Verma

The buyers, Montblanc observed, were not necessarily young professionals or entrepreneurs. Middle-aged consumers, and connoisseurs of luxury, too joined the party.

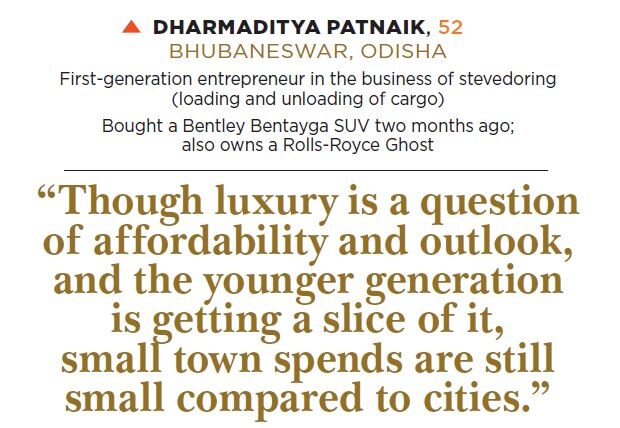

Take, for instance, Dharmaditya Patnaik in Bhubaneswar, Odisha. The 52-year-old first generation entrepreneur bought a Bentley Bentayga SUV, costing a couple of crores, two months ago. Patnaik, who is into the business of stevedoring (loading and unloading of cargo), also owns a Rolls-Royce Ghost. For him, luxury is all about affordability and outlook. “I first bought a pre-owned Rolls-Royce in 2001,” he recalls. Then he graduated to a Merc SL500, a two-door convertible (also pre-owned), in 2003, and finally a ‘fresh’ Rolls-Royce Ghost five years back. “Though the younger generation in smaller towns is more aware and getting hooked to luxury, cities still take the lead,” he reckons.

The next wave of growth is likely to get pronounced by 2025. Thanks to the nature of urbanisation taking place in India.

Image: Amit Verma

Image: Amit Verma

In a report published last year called ‘The new Indian: The many facets of a changing consumer’, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) pointed out the uniqueness of Indian urbanisation. The migration to urban centres, the report said, is not concentrated in a few cities as it is in countries such as Indonesia or Thailand. “In India, the population is booming in scores of small cities,” it noted. About 40 percent of India’s population will be living in urban areas by 2025, and these city dwellers will account for more than 60 percent of consumption. “Much of this growth will take place in small towns,” the report maintained.

In terms of consumption expenditures, too, emerging cities (those with populations of less than 1 million) are pegged to be the fastest growing. Fuelled by rising affluence, expenditures in these cities are rising by nearly 14 percent a year, while consumer spending in India’s biggest cities is increasing at about 12 percent a year, BCG noted. “We expect emerging cities to see the highest growth in the number of elite and affluent households through 2025,” the report highlights, adding that a small set of micro-markets are areas of big opportunity. “Twenty-two of the top 50 micro-markets in India (measured by the number of elite and affluent households), including 5 of the top 10, are in small cities,” BCG noted.

Amit Damani agrees. An increasing number of consumers from Bhilai, Varanasi, Mangaluru, Belagavi and Amravati are taking luxury villas on rent for holidaying, claims the co-founder of Vista Rooms, which deals with luxury villas in Maharashtra and Goa. “We are surprised. Demand from smaller towns has doubled over the last one year,” says Damani.

Back in Jabalpur, the Grover brothers don’t find the luxury boom in smaller towns surprising. “Gold is always at the bottom of the pyramid,” says Mayank. And for luxury, he continues, the bottom of the pyramid is not the lower economic section of the population but the lower strata of towns and cities. Big cities may be flashy and luxury brands need to be there, but the money in the long run will come from smaller places. “Jabalpur just has a Nexa showroom. No BMW, Audi or Merc. But there are scores of luxury cars,” he grins. “That tells you the story about small towns with big pockets and aspirations.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X