Can Indian carmakers kickstart the EV revolution?

The future's electric. And Indian auto makers are launching newer models and building an ecosystem as the government offers favourable policies and financial incentives

The Ora RI from China’s Great Wall Motors is touted as the world’s cheapest electric car

The Ora RI from China’s Great Wall Motors is touted as the world’s cheapest electric carImage: Ramesh Pathania / Mint Via Getty Images

The Indian automobile sector has endured some challenging years. Floundering sales on the back of an economic slowdown coupled with a transition to the more efficient BS VI engines with lower emission hit auto makers hard. Over the past year, sales of vehicles across categories fell by nearly 16 percent in the world’s fourth-largest automobile industry. Now, with the Covid-19 pandemic causing the global economy to go into a tailspin, the sector could take over a year to recover.

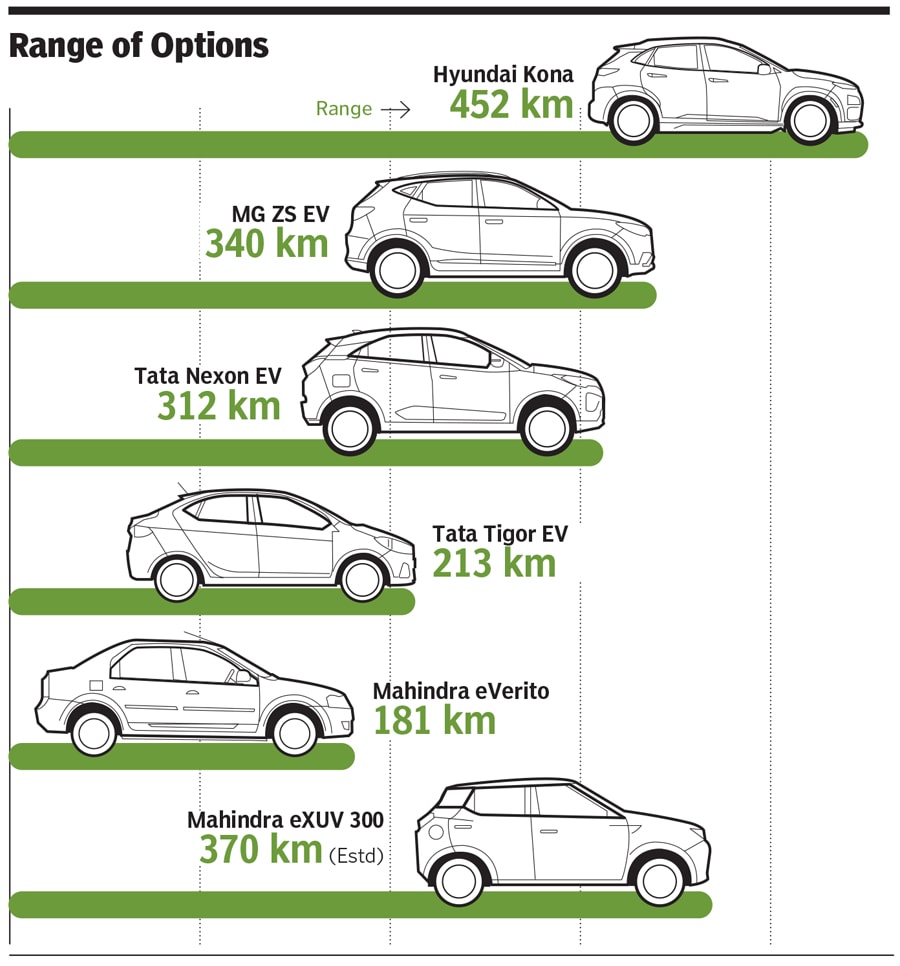

Amid the despondency, however, there appears to be a silver lining for the industry. Since January 2019, India’s top car manufacturers have been making a beeline to launch electric vehicles (EV). Last July, Hyundai, India’s second-largest car maker, launched the Kona—its first electric offering in India—with a range of 425 km. In October 2019, Tata Motors announced the launch of its first EV, the Tigor, followed by the electric version of its popular SUV, Nexon. In January, Mumbai-headquartered Mahindra followed suit with its electric SUV, e-KUV, which has a range between 130 km and 150 km.

At the Auto Expo in New Delhi earlier this year, much of the attention was on EVs with Maruti Suzuki’s Futuro-e, Tata Motors’ Altroz EV and the Ora R1 from China’s Great Wall Motors. Pune-headquartered domestic manufacturer Force Motors also announced its next-generation mobility platform featuring an electric powertrain while MG Motor India launched its electric SUV, its only second vehicle offering in India.

“Over the past two years, there has been a growing awareness in this space and the growth has been on the right path,” says Shailesh Chandra, president of electric mobility business at Tata Motors. “If you look at Q1FY20, sales were around 300 vehicles… the number rose to 500 in Q2, 800 in Q3 and is expected to hit 1,400 in Q4. While the Q3 sales were on the back of the fleet segment, the Q4 numbers will be on the back of personal purchases.”

The Futuro-e from Maruti Suzuki will pave the way for more EVs from the company

The Futuro-e from Maruti Suzuki will pave the way for more EVs from the company The sudden spurt in launches by Indian car makers comes at a time when Chinese companies—with their deep expertise in the EV industry—are making plans to foray into the Indian market. In 2018, China sold over 1.2 million EVs and is currently the world’s biggest EV market.

“With the Chinese auto makers getting ready to enter India, we will certainly see a huge shift in the landscape by 2022,” says Puneet Gupta, associate director for automotive sales forecasting at market researcher, IHS Markit.

For long, India’s EV industry found itself stuck in a quagmire, largely due to high prices of vehicles, fewer choices, unsteady policies and lack of a robust charging infrastructure. The last is essential to alleviate concerns of range anxiety, a fear that the vehicle will not have sufficient fuel to cover the distance it has set out to. “Now, there’s a ‘wow’ quotient if you drive electric vehicles, particularly in metros,” adds Gupta. “On an average, people who live in metros travel around 50 km a day… and with companies often providing charging stations, users have very few reasons to worry as the range anxiety concerns have been addressed.”

Mahindra charging station on display at Auto Expo 2020

Mahindra charging station on display at Auto Expo 2020

Gaining Momentum

Much of India’s EV journey began with the government’s FAME scheme, launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2015 to incentivise the production and promotion of EVs. It is currently in its second phase—which runs until March 2022 with an outlay of ₹10,000 crore. The scheme is only for the shared mobility segment, but it has played a crucial role in improving the overall EV landscape.

Around the same time, the government roped in Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL), a public sector company formed in collaboration with four public sector entities to procure 10,000 EVs for government organisations. “Although the incentives were put in place by 2015, it was by 2017 that affirmative steps were taken… things moved fast with the tender from EESL,” says Chandra of Tata Motors. “The EESL programme created the seed demand for commercialisation and activated the supply chain. The focus then was on keeping the total cost of ownership low.”

The decision to offer supportive government policies and financial incentives was based on models adopted in countries such as China and Norway, which had seen a large adoption of EVs. “From 2013 to 2017, total subsidies on EVs amounted to about RMB 50 billion ($7 billion) in China,” says Vinay Piparsania, consulting director—automotive, Counterpoint Technology Market Research. He explains that growth of EVs in China can be attributed to public procurement programmes, financial incentives reducing the purchase price of EVs, tighter fuel-economy standards and stringent emission regulations.

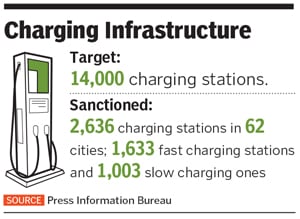

India is currently looking at having at least 15 percent of the total vehicles on its roads as electric by 2023. However, the country is grappling with charging infrastructure, forcing many players to turn their attention towards building their own ecosystem for EVs.

“The current charging infrastructure is almost nothing,” SS Kim, Hyundai Motors India’s managing director and CEO, told Forbes India in an earlier interview. “Even 1,000 charging stations will only cover a small pie. I expect the government to play a substantial role in extending the charging infrastructure. But we are developing more low-cost cars and vehicles with more range.”

Others are following suit in building cheaper cars and providing the necessary infrastructure. “Globally, the trend is about moving towards new energy,” says Rajeev Chaba, president and managing director of MG Motor India. “While we are still at a nascent stage, we are taking initiatives, including providing chargers for free to the buyers. MG is looking at launching another electric vehicle soon.” The company has partnered with Fortum, Delta Electronics and eChargeBays, offering fast, normal and house charging infrastructure.

Tata Motors, meanwhile, is working on an elaborate EV ecosystem where Tata Power will step in with the necessary charging infrastructure while Tata Chemicals has begun work on batteries for cars. Tata Power, which has already set up 100 charging stations, will add another 650 in more than 20 major cities over the next year. “Our new platforms are all designed in such a way that we can electrify with them,” says Chandra.

Smooth Ride

Indian auto makers are enthused with the initial response to EVs despite the teething problems. “So far bookings have been encouraging,” says Chandra about the demand for Tata Motors’ electric variant of its popular compact SUV, Nexon. “While the range continues to be the focus, we have our eyes on the price too.” The Nexon is priced at ₹13.99 lakh and goes up to ₹15.99 lakh depending on features. “We are constantly working towards improving the range. As emission norms become stricter for internal combustion engines and the price of EVs comes down, it makes more sense for buyers to tilt towards EVs,” says Chandra.

Tata Altroz EV unveiled at the Auto Expo 2020

Tata Altroz EV unveiled at the Auto Expo 2020

MG, too, is “overwhelmed” with the 3,000 bookings for its new EV. “In fact, the response has been better than what we had for the Hector,” says Chaba. Ahead of the EV launch, MG had set up 50 kW DC fast chargers at 11 of its dealerships across the country. They help charge the vehicle up to 80 percent in 50 minutes; it takes up to 8 hours to fully charge the car using home-based AC chargers.

Much of the reduction in EV prices could be a result of a decline in battery costs. “About 60 percent of the EV cost is batteries,” says Kanv Garg, director, renewables and electric mobility at consultancy firm, EY. “The EVs have very little moving parts, ride better and have lower operational maintenance. With supply chains becoming smoother and scales improving, the future is clearly electric.”

Indian auto makers have already invested a combined $6 billion to transition to BS-VI engines and many are expected to reap rich returns on them before focussing more on EVs. “That’s where the startups are stepping up the game because they don’t have investments on BS-VI. So, it becomes easier in the two-wheeler segment,” says Garg of EY. Already, companies like Hero MotoCorp and Bajaj, apart from a host of new-age tech companies like Revolt Intellicorp, Tork Motors and Ather Energy, have started to focus on electric two-wheelers.

“One of our strategic priorities is to enhance our participation in the EV space by pursuing our internal EV programme in addition to partnering with the external ecosystem, including startups, in a meaningful way,” says Bharatendu Kabi, spokesperson for Hero MotoCorp. “We see this as an important step in building the necessary ecosystem needed to support mass commercialisation of EVs in the country. It is with this objective that we have invested in Ather.”

Hero MotoCorp has set up a separate vertical that is entirely focussed on developing alternative mobility solutions. “This EV programme is working towards introducing mass-market products and solutions in a phased manner,” adds Kabi.

Kona is Hyundai’s first electric offering in India

Kona is Hyundai’s first electric offering in India

Not everyone is blindly jumping onto the EV bandwagon. Some prefer a staggered approach instead. Take, for instance, Maruti Suzuki, which sells one out of every two cars sold in India. “We are not only looking at EVs… our focus is on electrification of the fleet, from mild hybrid to fully electric vehicles, which will not only make vehicles more fuel-efficient and hence better for customers, but also reduce oil demand, thereby reducing oil imports for India,” says CV Raman, senior executive director and a member of the executive board at Maruti Suzuki.

Maruti Suzuki reckons that almost 90 percent of the sales in India in the passenger car segment is for models below ₹10 lakh, indicating the price-sensitive nature of the market. “At current prices, natural adoption of EVs without significant fiscal incentives will be a big challenge,” adds Raman. “Natural adoption of EVs with significant range will happen only when acquisition price comes below ₹10 lakh. The primary focus at present should be on targeting specific mobility segments that have high utilisation and minimum charging infra requirements. It should be to target public transport comprising buses, three-wheelers, four-wheeler taxis and two-wheelers followed by personal segment cars.”

Last year, the government reduced GST on EVs from 12 percent to 5 percent, in addition to providing income tax deduction of ₹1.5 lakh on interest paid on loans taken to buy EVs. Earlier this year, the government approved setting up 2,636 EV charging stations across 62 cities under the FAME scheme. Of these, 1,633 will be fast charging stations and 1,003 slow charging ones. The government aims to install around 14,000 charging stations across the selected cities.

“As of now, while we have removed range anxiety, the concern is on charging anxiety,” says Garg, who has also advised the government and companies on the EV shift. “The government removed taxes, delicenced the charging infrastructure, allowing anybody to set up charging infrastructure and making it mandatory for residential and commercial complexes to allot 20 percent of their parking space for EV charging facilities. Now, private auto makers and power companies have to come together to ensure that the ecosystem is developed.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)