Reimagining Indian IT

To maintain its share in the economy, the sector will have to reinvent its revenue model and technological capabilities

Image: Whitemocca / Shutterstock

Image: Whitemocca / Shutterstock

Last November, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), the $19-billion IT company that is larger than its next two Indian rivals combined, announced an expansion of its seven-year-old relationship with Rolls-Royce: The British jet engine-maker was taking a larger bet on its Indian IT supplier, giving TCS not only much more work, but also much higher-value work. “This would include innovation and collaboration,” TCS CEO Rajesh Gopinathan said at a November press conference in Bengaluru.

The aim was, he added, “to build a collaborative, open platform-based ecosystem where Rolls-Royce significantly amplifies the value it delivers to its customers”. Rolls-Royce, following its ‘digital first’ strategy, would be using a TCS platform called ‘Connected Universe’, which had been four years in the making at the Mumbai-headquartered company’s innovation labs. The platform, as TCS describes it, is an orchestra of multiple technologies that work in tandem to help businesses easily develop, deploy, and administer Internet-of-Things software applications such as web apps, real-time analytics, and batch analytics.

This stronger association was an exercise in tapping “the most extraordinary ecosystem”, said Ben Story, Rolls-Royce’s strategy and marketing director. “We work with TCS today on perfecting the digital twin.” TCS would help build virtual models—digital twins—of Rolls-Royce products, which could then be used for everything, from predicting problems with products under development, to preventive fixes and overhauls of mature products, such as aircraft turbines.

For Gopinathan, it was a testament to the company’s Business 4.0 strategy that he had championed and announced only a few months earlier. Business 4.0 is TCS’s formal framework for solving large business problems for customers by bringing together multiple tech capabilities and combining them with its deep business consulting abilities.

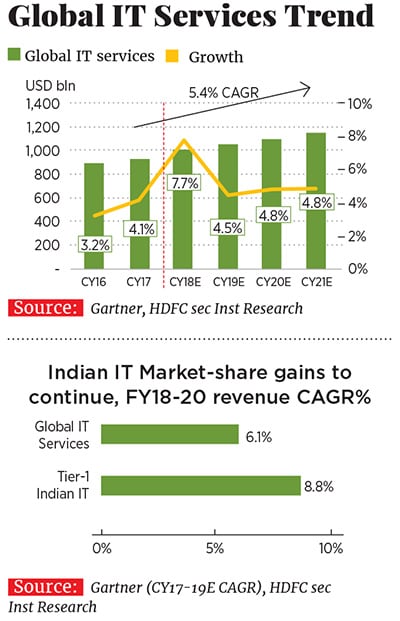

This development offers a glimpse into the future of Indian IT services providers at a time when their traditional outsourcing model is moribund. The IT and ITES sectors' contribution to GDP has dipped from a peak of 9.5 percent in 2014-15 to about 6.35 percent three years later. The Indian IT sector ended the financial year with exports of $126 billion, contributing 24 percent to the country’s total exports, according to industry lobby Nasscom. IT exports are projected to grow as much as by 9 percent in the current fiscal year. The IT company of the future will be one that harnesses expertise, builds multiple platforms of digital technologies, and delivers outcomes. It will rely less and less on providing cheap labour, and charging for time and material used.

"How do I invent my future, while delivering my present?" asks Rostow Ravanan, CEO, Mindtree

"How do I invent my future, while delivering my present?" asks Rostow Ravanan, CEO, MindtreeImage: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Therein lies the challenge, says Rostow Ravanan, CEO of Mindtree, Bengaluru. “How do I invent my future, while still delivering my present?” he asks. And for listed companies, there is the added compunction of delivering on each quarter’s numbers if they have to avoid shareholder ire. “Merely maintaining the present is a non-viable option,” says Ravanan.

This means, in a few years, some of the IT companies will no longer be pure-play services companies. Ravanan points to the successful transformation at Microsoft, which isn’t any longer a pure-play product company that develops software and sells licences. Microsoft is already building large software platforms—such as its Azure cloud platform—and winning significant subscription revenue with products such as its cloud-based Office 365 suite.

Just as companies such as Microsoft have moved a step closer to the centre of the spectrum—with pure-play product companies at one end, and pure-play services companies at the other—the Indian IT services companies too will have to shift towards the centre, thus changing their business models, contracts and revenue recognition. “Today my revenue is a fairly simple equation: The number of people I have, multiplied by the utilisation, multiplied by the charge-out rate,” Ravanan says. “That model is probably going to die in the next three to five years.”

IT companies will need to come up with ‘co-creation’ models that will provide customers with solutions to real business problems, he adds. Some of the skillsets and areas in which Indian IT companies need to ramp up are high-level design, architecture, user experience and product management.

For instance, a manufacturing company might still need business management software such as SAP, but the IT company won’t be asking for a fee for deploying the software package. Instead, it may have to look for a per-transaction fee—for invoices raised or payrolls processed and so on—like a usage-based utility. This will make factors like the number of people deployed by the IT company irrelevant.

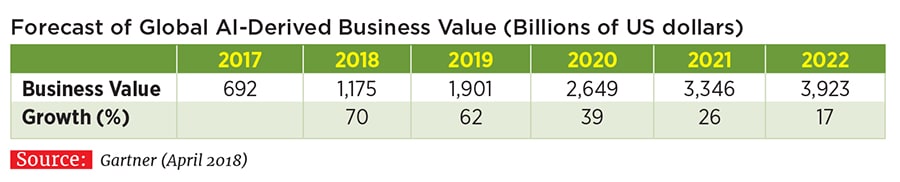

Underpinning everything will be the increased adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning and related technologies, said Michael Chui, a partner with consultancy McKinsey & Co in a recent podcast by the McKinsey Global Institute, along with institute chairman James Manyika. They said that although it is still early days for the adoption of AI technology, it has widespread potential, from sales and marketing, operations, risks, talent management, performance analysis and recruitment. “We see the potential for trillions of dollars of value to be created across the entire economy,” Chui added.

Being in a position to program things, and simplifying programming for others will happen soon

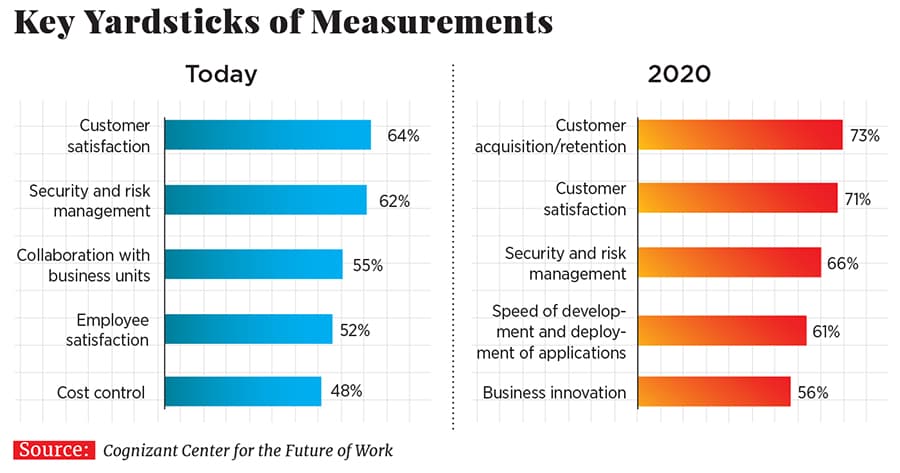

Being in a position to program things, and simplifying programming for others will happen soon To understand what is happening to IT services, one must first understand how IT itself is changing, and how the IT procurement departments of large corporations—typically embodied by the chief information officer—are changing, says Manish Bahl, senior director at Center for the Future of Work, at Cognizant Technology Solutions. “The days of the IT department being responsible for only IT infrastructure, with a relentless focus on cost reduction are gone.” Over the next two to three years, they will have to help business executives seal customer relationships, assist the organisation respond rapidly to market changes, and ensure security. “AI will fundamentally change the IT infrastructure procurement and consumption model over the next few years,” he adds.

What this means for IT services companies, says Anand Deshpande, founder and CEO of Pune’s Persistent Systems, is that the whole concept of IT being done by a certain set of people as distinct from the rest of the business is changing. “IT has become all-pervasive and is part of pretty much everything,” he says. “Everyone needs to be a programmer. But, on the other hand, programming itself is changing.”

Being in a position to program things, and simplifying programming for everyone’s ease are going to happen in the next few years. For instance, to ensure that self-driving cars drive themselves safely, and without glitches, is going to need sophisticated technology; however, it will need only the input of a destination and a few other pieces of information from the user. This will happen in every aspect of multiple businesses.

Deshpande reckons that businesses and society are probably at the beginning of an AI boom, with civilisation having reached the tipping point of data availability, and the requisite computing power to crunch that data. He explains how every business is going to become a software-driven business, and every activity will have software in some way. There is a large opportunity in building the next generation of AI systems, collecting data, and building infrastructure.

“There will be three layers to this opportunity,” he says. The first is the infrastructure: People will be required to collect data, and build algorithms and computing power. The second layer is of integration, meaning the building of applications useful for individuals. The third or the experience layer is where the end-user interacts with the product and what it does. This is also the layer in which the product—say a wearable medical device—collects and sends back data, which can be analysed, and the user alerted to future health scenarios.

This is only possible now because of the confluence of cloud computing and related technologies. To be able to do all this, IT companies will have to bring in domain expertise needed in each industry and marry it to software development.

Deshpande elaborates upon these possibilities with the example of the health care sector in the US, Indian IT industry’s biggest market. Traditionally, health care is incident-based, meaning, people go to a doctor when they fall sick. However, with health care costs going up dramatically, focus is shifting to wellness, where data can be used to help people maintain various health parameters within prescribed limits, rather than wait for a problem to manifest to a level that needs medical intervention.

This is a far cry from the current people factories that code billing software for telecom companies or energy utility firms. Software companies will have to evolve beyond rote effort-based models, because there won’t be much effort any more. This evolution will be discontinuous, says Mindtree’s Ravanan.

Ravanan believes that the IT industry will go through a period of discontinuous change over the next three to five years. In its first 20 to 25 years, the Indian IT industry helped its customers run their businesses more efficiently by reducing various transaction costs, such as the cost of issuing an airline ticket. These were back-office functions. In the last two to three years, technology has equally become a front-office function by influencing interactions with end-customers, and thus increasing revenues. Moving ahead, there is a discontinuous change happening with customer expectations.

In the previous waves of technology implementations—from Y2k or enterprise resource planning—the service providers understood technology better than customers. Today, broadly, “at least a third of our customers know more about technology than at least half the providers” put together, says Ravanan. Therefore, “we are having to scramble to catch up to the expectations of our customers”.

This also means traditional sales functions are being upended. Up until two or three years ago, IT sales people were comfortable selling capacity—say, 10 Java programmers or 50 SAP application developers. But “that model is already dead”, says Ravanan. Now, one has to sit with the customer and say, “What is the problem you’re trying to solve and how can we help?” Then the sales person will have to go back to the internal experts and figure out an acceptable solution for the customer.

Five years ago, hardcore coding would have constituted 70 to 80 percent of the software development done to fulfil an order; today that might be as little as 5 percent. “Large parts of what we do have become significantly different,” he says, adding that given the political and regulatory changes taking place, the current model will clearly be out in another three years.

This was perhaps aptly highlighted on April 19, at a press conference to announce TCS’s earnings as of March 31, when Gopinathan told reporters that he saw the previous year’s performance—which included a $50 million contract in its digital services business, its biggest yet—as representing a “turnaround” for the company, and he anticipated “double-digit growth” soon. Of its $19 billion revenue, TCS earns $4 billion from digital services.

Pointing to the future prospects of the industry, he added, “The largest deals can be structured if one has the breadth of offerings and the ability to integrate them with the aim of helping clients transform their businesses to bring exponential value to their end customers.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)