Shree Maruti Courier never aspired to be number 1. It became its secret sauce to success

With its focus on high speed delivery and steady growth, Shree Maruti Courier has survived competition from biggies, startups and countless clones to emerge as one of the top logistics players in India

(Left) Ajay Mokariya, Managing director, Shree Maruti Courier and Ram Mokariya, Founder, Shree Maruti Courier

Image: Mayur D Bhatt for Forbes India

(Left) Ajay Mokariya, Managing director, Shree Maruti Courier and Ram Mokariya, Founder, Shree Maruti Courier

Image: Mayur D Bhatt for Forbes India

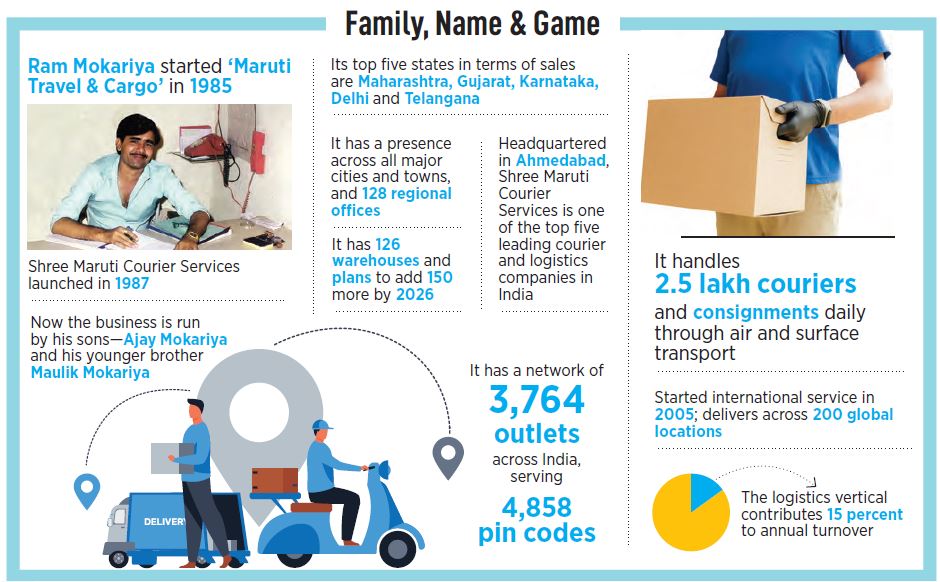

2022, Ahmedabad. Papa, isko unicorn bolte hain [father, this is known as a unicorn],” the seven-year-old said gleefully to his inquisitive father. After a quick low-down on the mesmerising creature—it’s a one-horned, white horse with magical powers—the kid got immersed in his favourite cartoon show on TV. “I was familiar with this word, but didn’t know what it meant,” confesses Ajay Mokariya, managing director of Ahmedabad-based Shree Maruti Courier, which was started by his father Ram Mokariya in 1985 in Porbandar, Gujarat. “Mujhe bas itna pata hai ki sabko unicorn banna hai [all I know is that everybody wants to become a unicorn],” the second-generation entrepreneur says laughing, alluding to the $1-billion or more valuation of a privately owned company which gives it a ‘unicorn’ tag.

Back in the beginning of 2016, Ajay heard a lot of unicorn noise. A bunch of intra and inter-city logistics startups—TheKarrier, TruckMandi, TruckSumo, LoadKhoj, Zaicus and SastaBhada—had snapped up loads of venture capital to fuel their hyper-ambitious goals. All had unicorn aspirations, all were in a tearing hurry to gallop, and all bought scores of trucks to add muscle to their fledgling operations. Later, many opted for an asset-light model of aggregating trucks to run the business. The plan was to have a vast network of suppliers raring to fulfil the demand.

Meanwhile Ajay, who joined the family business as a 20-year-old and started his stint as a delivery boy in 2003, was getting ready to roll out operations to a new city. He contacted a bunch of local vendors who offered trucks on rent, picked up the one offering the best price and started delivering couriers and packages on the new route. “For the first few months, taking vehicles on rent made sense,” he recounts, explaining the logic.

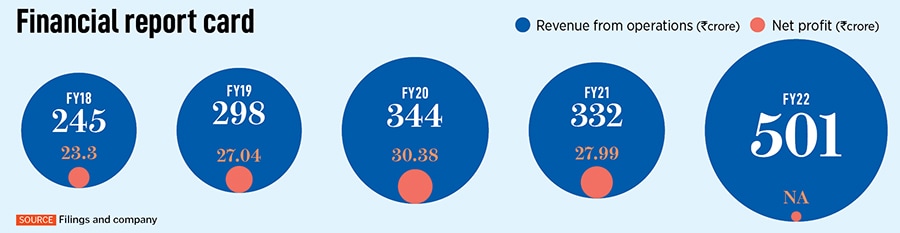

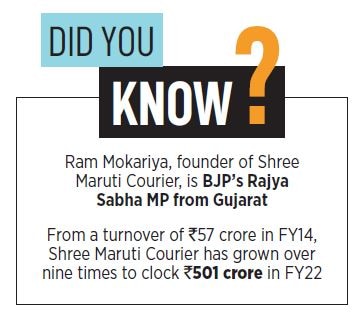

The idea was to gauge the reliability of demand and ascertain the sustainability. If demand persisted and exceeded targets, then the company would buy a vehicle, underlines Ajay. Shree Maruti Courier bought its first truck in 2004, had an operational revenue of ₹121 crore in FY16, and had 60 owned vehicles by the end of the calendar year. The three-decade-old business, with no external funding or borrowing, was clearly trotting now.

The idea was to gauge the reliability of demand and ascertain the sustainability. If demand persisted and exceeded targets, then the company would buy a vehicle, underlines Ajay. Shree Maruti Courier bought its first truck in 2004, had an operational revenue of ₹121 crore in FY16, and had 60 owned vehicles by the end of the calendar year. The three-decade-old business, with no external funding or borrowing, was clearly trotting now.

But 60 trucks in a dozen years? Is the pace of growth not too slow? Did Ajay trade-off speed for stability? The second-gen entrepreneur, who now runs the show with his brother Maulik, begs to differ.