Cricketer Harmanpreet Kaur tears down the boundaries

With her destructive game, Harmanpreet Kaur has broken down gender divides and has given women's cricket the visibility it never had

Harmanpreet Kaur

Harmanpreet KaurImage: Amit Verma

Their worlds might be poles apart, but in Nobel Laureate Abhijit Banerjee, Harmanpreet Kaur, arguably the biggest game changer for women’s cricket in India, has an unlikely ally. Sometime this October, when word reached Banerjee that he has won the award for his experimental approach to alleviating poverty, the economist, admittedly not a morning person, is said to have gone back to bed. “I figured it would be a fault to the system if I don’t continue my sleep,” Banerjee told the Nobelprize.org of his reaction to the pre-dawn call from Stockholm.

It’s a sentiment that Harmanpreet deeply appreciates. “If I don’t get my sleep, I feel restless,” says the captain of the Indian T20 team, who’s also the first Indian cricketer to play a hundred T20 internationals. “Main kabhi bhi, kahin bhi so sakti hoon [I can sleep anywhere, anytime].” Her love for sleep extends even to the cricket field—a sleep-inducing match isn’t a mere figure of speech for the 30-year-old. “Agar game thodi si bhi boring hoti hai, mujhe neend aati hai [if the game is even slightly boring, I feel sleepy].”

It’s another matter though that when Harmanpreet is at the crease, one can kiss sleep goodbye. Standing barely five-and-a-half-feet tall, and her hair neatly tied in a ponytail like a schoolgirl, she doesn’t look the part. But once at the crease, this wiry girl from the Punjab small-town of Moga can send the crowd into delirium with her six-hitting abilities, just like her idol Virender Sehwag.

A glimpse of Harmanpreet’s Goliath-like avatar was evident back in 2009 when, playing her first tournament with the national team at the World Cup in Australia, she was asked to undergo a dope test for a six that she hoicked onto the roof of the stadium.

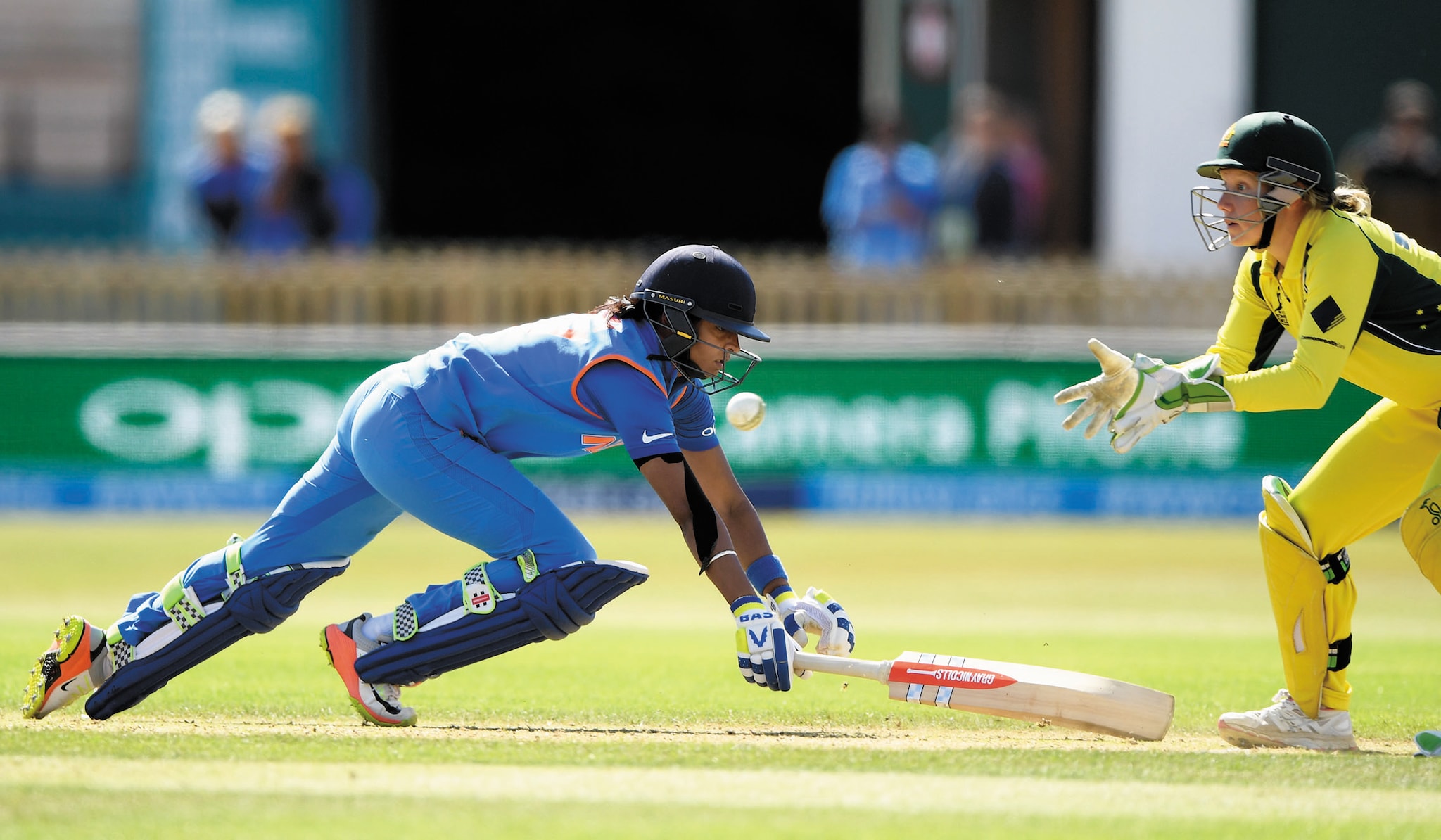

But what defines Harmanpreet is her innings of 171 not out in 115 balls against Australia, in the semis of the 2017 one-day internationals (ODI) World Cup that, even two years on, is referenced as among the most disruptive ever for women’s cricket. “That is the best innings I have witnessed in an ODI. We had no answers to her,” says Alex Blackwell, who top-scored for the Aussies that day. Its parallel in the Indian cricketing universe is sought in Kapil Dev’s innings of 175 not out against Zimbabwe during the 1983 World Cup that catapulted the team from being the invisibles to the invincibles: Like Dev, Harmanpreet extricated the game out of relative obscurity and embedded it in popular imagination. In the Diana Eduljees, Anjum Chopras and Mithali Rajs, women’s cricket has had its shining stars through the preceding decades, but Harmanpreet has changed the syntax of the game, giving it the ballast and sinew like never before.

Harmanpreet continues to plunder bowling attacks in similar fashion even now: She hit 11 sixes, one short of South Africa’s Lizelle Lee who hit the most, during the 2017 World Cup; in November 2018 during the T20 World Cup in the Caribbean, she totalled 13, eight of which came in a blitzkrieg of 103 in the opening match against New Zealand. It was also the first T20 international century by an Indian woman, heroics that earned Harmanpreet the captain’s spot in the International Cricket Council’s (ICC) world T20 team of the year. As her teammate Poonam Yadav, the pint-sized spinner and Arjuna awardee, puts it pithily, “Harmanpreet can change the game any moment. She has immense power, chhakke maarna toh uske baaye haath ka khel hai [she can hit sixes with her left hand].”

Harmanpreet Kaur’s 171 not out against Australia in the semis of the 2017 World Cup is regarded as among the most disruptive innings

Harmanpreet Kaur’s 171 not out against Australia in the semis of the 2017 World Cup is regarded as among the most disruptive innings“She had a lot of raw power. She wasn’t really girly. She was born to be an athlete. You put her in any sport and she would have done well,” says Yadwinder Singh Sodhi, Harmanpreet’s first coach. Yadwinder’s father Kamaldheesh Sodhi, the principal of Gian Jyoti School in Moga’s Darapur village, took a young Harmanpreet under his wing and brought her to study in the school in 2006 after watching her take the local bowlers to the cleaners. Says Yadwinder, “My brother would play cricket too, so whatever equipment he got, Harman would get too. But she was far more hardworking. If kids were asked to run around the ground during warm-ups, my brother would run two laps and Harman six. Mere bhai ko cricket khelne ka shauk tha, Harman ko India khelne ka [my brother wanted to play cricket, Harman wanted to play for India].”

WINDS OF CHANGE

While India were runners-up in the 2017 women’s World Cup (the second time since 2005), over 180 million people were estimated to have watched the tournament around the world that summer, a near-300 percent increase in viewing hours compared to the 2013 edition. According to the ICC, about 156 million viewers were in India, of which 126 million watched the final alone. “India’s fine performances contributed to a 500 percent increase in viewing hours,” mentions the ICC website, and Harmanpreet’s blinder in the semis, which she played on an empty stomach and while carrying a shoulder niggle, would have contributed significantly to that spike.

“The 2017 performance brought many changes to the game, most importantly, spectators. We get them in every match now. It’s so boring to play in empty stadiums, when we have to motivate each other and tell each other ‘come on yaar’,” says Harmanpreet. “Each player enjoyed the series against South Africa in Surat and Vadodara in September and October because we played in front of a full stadium with the spectators shouting out our names. That has never happened before.”

The 10,000-plus fans that turned up at the Lalbhai Contractor stadium in Surat for the series and the vuvuzelas that blared with the gusto of an Indian Premier League game were a stirring indication of the visibility women’s cricket has been amassing of late. As are the videos she receives of young girls playing, and calls her manager receives with kids pleading, “Harman didi se baat karni hai [we want to talk to Harman].”

Her extraordinary agility on the field, manifested through a flying one-handed catch on the boundary in the recent series against West Indies, has spawned hashtags and Twitter threads. And her exploits have earned her enough recognition for the souvenir store at Manchester United, her favourite football club, to offer her a 20 percent membership discount. “She spent all her money there,” jokes Kate Cross, her teammate at Lancashire Thunder, the side for which Harmanpreet chose to play at the Kia Super League just because it was home to the Red Devils.

India’s 2017 World Cup campaign also brought money to the game. The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) awarded ₹50 lakh to each cricketer for making it to the final and revised their pay grades, while Harmanpreet became the first Indian woman cricketer to bag a bat endorsement deal with Ceat. “Back then, we had Rohit [Sharma] and Ajinkya [Rahane], but we thought it’s also important to promote women’s cricket. Who better than Harmanpreet to go with our philosophy of bringing on board prolific cricketers,” says Amit Tolani, chief marketing officer of Ceat.

Harmanpreet now has five brand endorsement deals, the highest for a woman cricketer in the country, along with Smriti Mandhana, and has made her debut on the Forbes India Celebrity 100 List at No 91. But her success isn’t contained in these specifics, and instead lies in prising open a much-elusive chest that women cricketers were not privy to, which allows young prodigies—like Mandhana and Jemimah Rodrigues—to command a brand value that’s unheard of. “If you look at her story, she has excelled in a game that is seen as the bastion of male dominance, and has come from a region that is known for male chauvinism. You can imagine how difficult it must have been for Harmanpreet to rise above these forces and become an inspirational figure,” says Sanjay Singal, COO, dairy and beverages, foods division, ITC, which has signed Harmanpreet as an ambassador for juice brand B Natural.

It’s still a long way off before women cricketers can catch up with the Virat Kohlis and Mahendra Singh Dhonis—not just in endorsements, but also in central contracts that pay ₹7 crore to top-grade male cricketers against ₹50 lakh to women—but Harmanpreet has given her tribe a fighting start to the race.

JOURNEY TO THE TOP

Rising fame, though, brings in sleep deficit. Harmanpreet can no longer indulge her favourite pastime as well as she could during her growing-up years, waking up around noon and heading for practice. Two days after the series against South Africa concluded, Harmanpreet was in Chandigarh via Delhi for media and commercial commitments, where Forbes India caught up with her. Once done, she would drive down to Patiala to spend a few days with friends and family before flying off to the West Indies for a month-long tour.

That her sleep schedule would have to be reworked emerged during a phone call in 2009 to a friend in Mumbai, who, in turn, asked for a party. “‘What for?’ I asked her. And she said, ‘Because of your selection in the national team’. The team for the 2009 World Cup was declared a month ago and here I was getting to know only two days before the national camp,” recalls Harmanpreet.

When her father Harmandar and coach Yadwinder went to drop her at the Delhi airport for the World Cup in Australia, a nervous Harmanpreet asked them for a primer on how to use an ATM card. Her apprehensions played out in the dressing room, too, as, at 20, she was fast-tracked into the senior team within a year of playing in the school nationals and was fraught with self-doubt. “For those times, I have Anjum Chopra and Jhulan Goswami to thank for helping me keep my jangled nerves together,” she says.

Says Chopra of the wet-behind-the-ears Harmanpreet, “Young players who make it to the team are talented already. What they need are some encouraging words. When Harman came in, my job was to do that unconditionally. In the match against Australia in the 2009 World Cup, I got her promoted in the batting order. I wasn’t the captain then but I managed to convince the coach. And she played a cameo of 19 from eight deliveries.”

It gave her enough confidence, for Harmanpreet now returns the favour to the game by making her juniors feel at home. As is evident from the testimony of Ramesh Powar, the coach of the Indian team for the T20 World Cup last year: “Harmanpreet has evolved from a listener to a communicator and ticks all the right boxes that a captain should—spending time with her juniors, taking them out for dinners, staying accessible.”

Mumbai landed the next jolt to Harmanpreet’s system in 2014, when she moved to the city with a job with Western Railway. “I stayed in Mumbai for nearly four years but never enjoyed it,” says Harmanpreet. I had to wake up early, train, go to work for a few hours and then return to training. It was hectic, shuttling between Bandra, where I lived, Mumbai Central, where I worked, and Bandra-Kurla Complex or Lower Parel, where I trained. But Mumbai taught a lazy person like me the value of time management. If you slack off, you’ll lose out,” she says.

Cricket became a vehicle of personal growth later in life as well, when, in 2016, Harmanpreet became the first Indian cricketer to be signed on to play T20 leagues abroad: She joined Sydney Thunder in the Women’s Big Bash League (WBBL)in Australia. In his autobiography 281 And Beyond, former India batsman VVS Laxman recalls his time in the exacting Bradford League in England in 1995—where, besides playing and running a household on his own, he also worked part-time at a petrol pump—as a learning curve that pushed him out of his comfort zone and helped him grow.

So it has been for Harmanpreet, whose cocooned life was shattered when she first boarded the flight to Australia to play in the WBBL. From her mother preparing her food, ironing her clothes and packing her kitbag, to being “looked after” by team managers during international tours, Harmanpreet was now responsible for every granular detail of her day-to-day life—from doing the dishes to planning her way to the stadium in time for matches. “When I went to Australia to play in the WBBL for the first time, I wondered, life mein kapda dhona, khaana banana, yeh sab bhi karna padta hai [life was about cooking and cleaning too]? Yeh sab toh pata hi nahi tha [I wasn’t aware of this],” she says.

But when the going gets tough, Harmanpreet gets going. For her debut match for the Lancashire Thunder in 2018, she landed in the UK early in the morning, and then got onto the bus for London, having barely slept at all, to play a match at the Kia Oval.

Sleep-deprived and jetlagged, she hit a six off the penultimate ball to bring home a win for her team. “Harman has an infectious calmness about her. She doesn’t go out and play her big shots from ball one, but allows herself the chance to get in and then is able to control the tempo of her innings,” says Cross, her teammate and current captain at Lancashire Thunder.

Concurs Powar. “Her clarity is an advantage for her. When I had a chat with her after I joined, I figured she had a lot of ideas and had ownership of the team. She told me we don’t have much depth in our batting and that we should build a longer batting lineup. I wasn’t expecting such clarity straightaway. She was leading the team from the front and that was making my job easier. Captains, and not managers, run the team, and I was surprised at how well she was doing that.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

Ten years into her international career, Harmanpreet has now made the dressing room her own, having assumed the mantle of a senior. She’s now as much at home doing a bhangra jig, or rustling up a sketch of her teammates—“She’d drawn one of mine, par bahut hi bakwaas tha (it was horrible),” jokes Poonam Yadav—as she is broaching subjects considered pariahs in the past, like the need for psychologists. “Women cricketers, unlike the men, aren’t used to playing in front of the camera. While it brings out the best in some, it piles pressure on some others. It would be good if there is someone to talk to when pressure situations overwhelm us,” says Harmanpreet.

She’s herself been under scrutiny a few times in her career, most recently during the T20 World Cup, where Raj was left out during the team’s semifinal loss to England. Raj shot off an angry letter to the BCCI, accusing Powar of bias and Harmanpreet of supporting his decision. Reams have been written about the clash, and the recent visibility of women’s cricket has meant that even a layperson has spared an opinion on the issue. Harmanpreet explains it as “one bad day in office” that cost them a lot. But she’s moved on. “Criticism doesn’t affect me because I don’t keep track of what is being said about me. Not the good things, neither the bad.”

The positivity has rubbed off from her father, a star in Moga’s cricket circle back in the day who lived and played like a king. “When we were young, if we told him that we’d like to take candies to our school on our birthday, he would say, “Sirf kal kyun, har din leke jaana [take them every day, not just on birthdays]. Diwali, for him, could be celebrated on any given day.” On the field too, he would hit sixes with such magnanimity that a young Harmanpreet assumed that was the way to play the game.

In fact, she still gleans cricketing wisdom from her family, now from her brother Gurjinder ‘Gary’ Bhullar, a champion in Moga’s tennis ball-cricket circuit that features short-format games with complete tournaments in a day. In pressure-cooker situations, her brother has taught her to break down chases not in terms of singles but sixes and fours that are aplenty in T20s, Harmanpreet’s fiefdom. “He taught me 25 runs off eight balls should be considered as a mere matter of hitting four sixes; it helps reduce pressure.”

What after cricket? A thought that really hasn’t crossed her mind. “I don’t know. Can’t think of life without cricket,” she smiles sheepishly. “Maybe I can slather my food with the home-churned butter that my mother makes once the diet restrictions are off. Or papa will finally let me buy a Harley-Davidson, since I am not allowed to ride a bike right now.”

The World Cup, of course, is a tangible dream, but any player worth her salt knows not to judge one’s career by that singular benchmark. Anjum Chopra certainly doesn’t. “Sure it would be a milestone, but I wouldn’t measure her success with that. She still has a lot to offer to the sport globally and deliver more than what she has already done. No one, least of all her, should be thinking about Harmanpreet’s retirement now,” she says.

Harmanpreet Kaur might have turned over a new leaf for women’s cricket in India, but the game would still want her to go miles before she can sleep.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)