The World According To Carlos Slim - World's Richest Man

The planet’s richest person has technically retired to focus on his foundation. But he’s keeping a sharp eye on his gigantic businesses—and on global affairs

Amid the threat of a Greek debt default and a recession in Europe, Carlos Slim Helú has some words of advice for political leaders: You’re doing it wrong. Slim, a Mexican entrepreneur who built a $69 billion fortune over nearly five decades, thinks governments should stop trying to shrink budget deficits by shortchanging education. “I am very concerned about the world in general. I think the solutions that [political leaders] are looking at are not the right solutions,” he says. “They are not looking for a different way to solve the problem.”

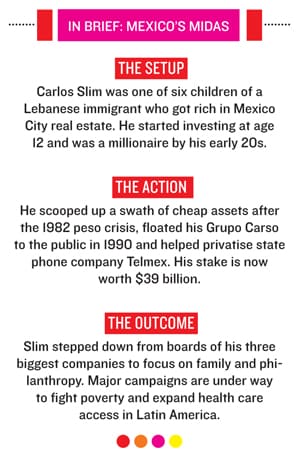

The world’s richest person, it turns out, has time these days to ponder weightier issues than where he should invest next. Since 2004 Slim, who recently turned 72, has stepped down from the boards of three of his largest companies. He wants nothing more than to tell me, when we meet at his Mexico City office in late January, how he would solve the challenges facing Europe, the US and Mexico. He likes to talk and likes to revisit his roots.

We are sitting in heavy wooden chairs against the wall of books in his office when he gets up to grab a notebook he kept when he was 17. In it he had recorded his pay, 200 pesos a week, for working at his family’s company. Another entry noted that his mother had lent him 5,000 pesos to buy stocks.

Slim’s business empire is dominated by telecommunications but also includes finance, mining, real estate, infrastructure, retailing and heavy industry. His biggest success by far began with the $1.76 billion privatisation of state-owned phone company Telmex in late 1990, led by his industrial conglomerate, Grupo Carso, alongside France Telecom and Southwestern Bell (now AT&T). Last year Telmex became part of América Móvil, a much expanded version of Telmex’s onetime cellular arm. Slim’s 43 percent stake in the pan-Latin American company clocks in at nearly $39 billion—more than half of his current net worth.

Given this history, it’s not surprising that privatisation of state-owned assets is Slim’s first suggestion for struggling European economies. “Let’s talk about Spain. It has a lot of highways, and they are all free,” he says. “They should charge users and sell [the highways] to the private sector.” The government can use the money from selling the highways to avoid making big cuts in social programmes, Slim advises.

Unemployment must also be addressed, he says. “The problem is that people have no jobs and no hope.” When I suggest that creating jobs takes time, he disagrees. “Some investments create a lot of jobs and other investments don’t.” His counsel: Invest in small and medium-size businesses, the engines of job creation, in labour-intensive industries such as tourism, health care, education and entertainment.

Turning to the US, Slim sees a pressing need for better regulation of the banking system, including the requirement that risky derivatives be carried on financial institutions’ books. He reminds me that he founded his financial group, Inbursa, as a brokerage in 1965. It has since expanded to include a bank and an insurance company, and sports a market capitalisation of $14 billion. “We’ve had growth for 47 years. We have never lost money, even in the worst times of our country,” he boasts, noting that Inbursa never needed the government’s help. “We don’t look for size. We look for quality.” Take that, Citigroup.

Slim has put his sons, Carlos, Marco Antonio and Patrick, in charge of the industrial, finance and telecom companies he acquired or started. But he’s clearly still engaged. His son-in-law Arturo Elías Ayub, who directs strategic alliances, communications and institutional relations at Telmex but essentially serves as one of Slim’s right-hand men, tells me: “He decides what companies to buy, and I go and buy them.”

What’s next for the Slim conglomerate? For starters, more investment in his mining business, Minera Frisco, a company created in early 2011 when Slim spun off mining assets owned by Grupo Carso into its own Mexican-stock-exchange-traded entity. The decision was a smart one. Buoyed by high prices for precious metals, the market capitalisation of Minera Frisco has soared to a recent $11.7 billion, 25 percent greater than that of its former parent, Grupo Carso.

“This company used to be medium-size, but it has the opportunity to grow and become a great mining company,” says Slim. Some would argue that Frisco is still medium-size—revenue for 2011 was $665 million. Investors are clearly expecting enormous growth.

As for telecom, América Móvil will invest around $9 billion annually over the next four years, improving its mobile and fixed-line networks throughout Latin America so it can transmit data more quickly. “We are going for faster speed,” says Slim. One area of focus, he adds, is connecting small and medium-size businesses to the internet.

In Mexico many consider Slim a telecom monopolist because his companies have roughly 70 percent of the wireless market and an 80 percent share of landlines. Critics blame him for excessive prices, and a report released by the OECD in late January (after our interview) stated that the lack of competition in Mexico in telecommunications has led to high prices for consumers and businesses and has cost the Mexican economy $25 billion a year. Slim vehemently disagrees.

Even before that report came out Slim was eager to rebut the charges of high prices when I mentioned them. “That’s what competitors say, but if that were true, they would take the market from us,” he says, bristling a bit. “The customers are not fools.” He pulls out a chart from a December report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch showing wireless revenues at 4 cents per minute in Mexico, nearly as low as the US, with 3 cents.

“That’s quite a cynical take on monopoly pricing power and cost structures,” says billionaire Ricardo Salinas, who is chairman of mobile network competitor Iusacell and also controls Mexico’s number two broadcaster, Azteca. “What Mexico needs is a level regulatory playing field that makes long-term competition feasible. There’s a fear with some government officials to take on the status quo.”

The rise in Slim’s net worth over the past three decades has been nothing short of remarkable. He first appeared on Forbes’ Billionaires list in 1991 at $1.7 billion. Nine years later Telmex split off its mobile phone service business into América Móvil, which listed its shares on the New York Stock Exchange in early 2001. By then Slim’s net worth had grown to $10.8 billion.

In the following years América Móvil acquired mobile phone network operators throughout Central America and South America—it now operates in 18 countries, including Mexico and the US. Between 2004 and 2008 its split-adjusted share price grew sixfold to $30. That propelled Slim, with a $60 billion fortune, to move ahead of longtime number one richest man Bill Gates in 2008. Slim held the title of world’s richest man again in 2010, 2011 and this year.

When I ask Slim how his life has changed over two decades as an ever richer billionaire, he quips, “It’s not money.” (True—it’s primarily the value of shares he and his family own in public companies.) Then he adds that his life hasn’t changed at all. Like Warren Buffett, he’s lived in the same house for much of his adult life.

I press him again, and Slim does admit that having great wealth has indeed changed things. “I have more activity, more responsibility and more compromise,” he says. The compromise, he explains, is the challenge of solving Mexico’s problems. “I’m trying to make our country better in the areas that I can. I am not the police,” he adds, alluding to Mexico’s ongoing, bloody battle against the drug cartels. He wants his six children and his grandchildren (all 19 of them) to follow in his footsteps and do even more work to help Mexico change. Slim, whose wife, Soumaya, died in 1999, makes sure to see his family at least once a week.

His biggest goal is a fight against poverty—but not for the usual reasons. “It’s good economically. In the past it was something ethical and moral,” he asserts. “To take poor people out of poverty and put them in the modern economy is very good for the economy, for the country, for society and for business. It is the best investment.”

It’s not something that should be left to the government, either. “I think that businessmen and entrepreneurs have more experience managing resources, and we can more easily solve the problems than politicians, who have other views. They are thinking about elections, they are thinking about popularity,” says Slim. “I don’t think that giving money should be something done for personal popularity.”

But how to do so? Slim is sceptical of traditional charity. “I am convinced that the private sector needs to give support, not money, because charity has not solved poverty in hundreds of years.” He believes the best course for chipping away at poverty is using digital tools for education to, as he says, “create human capital.” That’s where Telmex, the Carlos Slim Foundation and the Telmex Foundation come in.

The latest endeavour of Slim’s two foundations and Telmex is a system of digital libraries. “Now, instead of going to the library, you go to a digital library where you can navigate [computers] completely free,” says Slim. “Instead of lending a book, we’ll lend a laptop for 15 days.” There are some 3,500 digital libraries. Slim’s aim is to enable 60 percent of Latin America to have access to computers by 2015—the same timeline set by the United Nations Millennium Devel opment Goals. So far these new-fangled libraries are only in Mexico.

Slim won’t say how much of his fortune he plans on giving away eventually. So far he’s put a total of $4 billion into the Carlos Slim Foundation. Its main areas of focus are education and health. “It’s about the development of people’s potential. He wants to make it easier for people to generate wealth,” explains Alejandro Soberón, the chief executive of entertainment company CIE and a longtime América Móvil board member. “I travel all over Latin America, and I don’t think there’s another businessman who’s had the impact he’s had on health and education.”

In 2010, the Slim Foundation partnered with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the government of Spain in a five-year programme to improve the health of the poorest 20 percent of the population in southern Mexico and Central America; each partner contributed $50 million.

With the Broad Institute of MIT & Harvard (funded by Los Angeles billionaire Eli Broad), Slim’s foundation began collaborating in 2010 on a three-year study of the genomic roots of cancer and type 2 diabetes in Mexican and Latin American populations, with the Slim Foundation paying $65 million.

“It’s a visionary piece of philanthropy,” says Broad Institute director Eric Lander, explaining that in cancer the researchers were looking for mutations to help guide treatment. The researchers have already discovered genes linked to breast cancer, head and neck cancer and diabetes.

The Carlos Slim Health Institute has spent about $20 million since 2001 on organ transplants in Mexico, a nation with one of the lowest rates in Latin America for organ donations after death. It’s a philanthropy born of personal tragedy. Slim’s wife, Soumaya, died of kidney disease after getting a kidney transplant, and in 2008 his son Patrick was diagnosed with kidney disease. His brother Carlos gave him one of his kidneys. In a separate case, Slim’s daughter Vanessa donated a kidney to her brother Marco Antonio. The family now campaigns for organ donation and has funded 7,100 transplants in the past decade.

As evidenced by the works of American artist Conrad Wise Chapman hanging on the walls in his office at Grupo Financiero Inbursa and the private art gallery with the small Rodin sculptures just a short walk down the hallway, Slim is passionate about art.

He opened a huge new museum in March last year, the Museo Soumaya, a strikingly undulating, mirrored building designed by his son-in-law architect Fernando Romero. It showcases some 3,400 of the 64,000 pieces of art Slim has collected. He beams as he recounts the total number of visitors to date (650,000) and the fact that many are from schools and low-income groups or are people with disabilities. He is doing his part to educate and enlighten his countrymen.

Entrance is free, and the crowds lined up outside before the 10:30 a.m. opening on a balmy late January morning. Inside, the building’s circular walkways connecting one floor to another are somewhat reminiscent of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. But the eclectic collection—from Rodin and Dalí sculptures, old Mexican coins and Thomas Edison’s first phonograph to Matisse paintings and Diego Rivera murals—makes for an almost overwhelming mix. This is the collection of a man whose curiosities, and whose wallet, know few limits.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)