Stef Wertheimer - The Capitalist Kibbutz

Industrial parks are Stef Wertheimer’s weapon of choice in the fight to end conflict in the Middle East

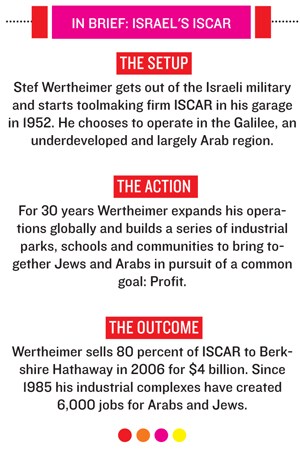

Much has changed for Stef Wertheimer since Forbes last talked with the Israeli industrialist in 1995. For one, he’s become a billionaire. In 2006 Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway paid $4 billion in cash for 80 percent of Wertheimer’s precision metalworking tool company, ISCAR. To date it remains one of Berkshire’s five largest non-insurance-company holdings, and while its vital statistics are jealously guarded by the investment firm, in his latest letter to shareholders Buffett described ISCAR as a company that “continues to amaze.” ISCAR emerged with record profits in 2011 despite taking a huge hit on Tungaloy, the Japanese toolmaker acquired in 2008 and crippled in last year’s tsunami.

ISCAR was Berkshire Hathaway’s first major overseas acquisition, and the deal vaulted Wertheimer into the ranks of the global business elite. What Buffett was also buying into was a highly successful and unsung peacemaking effort.

Capitalism, the 82-year-old Wertheimer insists, is better equipped than politics and diplomacy to solve the conflict that has rocked Israel since its founding. If a primary source of tension between Arabs and Jews is economic disparity, he has the countermeasure: The humble industrial park.

Israeli Arab households make, on average, 58 percent of the income of their Jewish counterparts, says Shlomo Hasson of the University of Maryland.

Arab men make 69 percent of what Jewish men make, and the proportion of Arab women in the labour market is three times lower than that of Jewish women. Regionally the disparities are even more striking. Israel’s GDP per capita has grown to $31,000, while Lebanon’s sits at $15,600 and Jordan’s languishes at $5,900, according to the International Monetary Fund. In the Palestinian territories the figure is an astonishing $2,800, according to the World Factbook. Compare that to oil-rich nations—$103,000 for Qatar, $48,600 for the UAE—and the stereotyping problem emerges. “There are many who believe that the only thing in the Middle East is oil,” Wertheimer says. “And if you are not in on oil, then there is nothing for you. If you want to get people out of the frustration created by the culture of oil, the only way out is industry.”

To that end, Wertheimer has invested over $100 million to build seven industrial parks in economically liminal regions of the Middle East. These operate as incubators for export-minded industrial startups. Since 1985 those complexes have nurtured 260 companies that have created 6,000 jobs. Firms operating in the parks yield an average of $200,000 in sales per employee, notably higher than Israel’s average. Eighty percent of that is for export.

ISCAR’s payroll is a model of integration; of its 3,000 Israeli employees, roughly half are Jewish and half Arab. ISCAR employs another 12,000 people around the world.

Wertheimer’s latest project, Nazareth Industrial Park, will be the first built in the city that has Israel’s largest Arab community, with a population of 67,000 and another 70,000 in the surrounding area. Unlike Wertheimer’s other complexes, which focussed on training workers before putting them in jobs, Nazareth Industrial Park will have the benefit of drawing from an already sizable skilled labour force. The park will sit below Mount Precipice, where, according to the Bible, Jesus was chased away following a sermon in which he denounced the healing capacity of prophets who had come before him. As it turned out, even Jesus needed a lesson in tolerance.

The parks enterprise has produced no profit for Wertheimer. “I am happy if it breaks even,” he laughs. “In the long term it will make a profit. For the next 20 years it probably will not.” He is far more interested in seeing his tenants succeed than he is in seeing them pay rent. ISCAR, which has a network of affiliates and subsidiaries in over 60 countries, now has managers in places as far-flung as China who started as students at his training academies.

In 1952 Wertheimer had just finished serving on a demolitions squad in the nascent Israeli military when he opened ISCAR out of his garage in Nahariya, a town in the Galilee, an underdeveloped, largely agricultural and very Arab region in northern Israel. It was far from the centres of government, which appealed to Wertheimer, and he received government incentives for setting up shop there. Even then he was keen on bringing together Arabs and Jews through work as a way to foster understanding and peace.

Wertheimer had a stint in politics, serving in the Knesset from 1977 until 1981. His last year in politics was also the year he established Kfar Vradim, a residential community near Nahariya with cozy homes, a vigorous community activity schedule and walkable woodlands. Kfar Vradim was the honey he used to draw entrepreneurs for his next big expansion, the Tefen Industrial Park. The complex, built in 1985, is just a five-minute drive from Kfar Vradim and has a postal service, a shared dining hall, a museum of modern art, a collection of vintage cars and a tennis court. There is an alternative school that educates over 500 students of various ages on industry and creativity.

With the opening of another Zur campus at Tefen in 1994, Wertheimer now had a perfect industrial microcosm. Or, as he calls it, a “capitalistic kibbutz.” New businesses recruit from Galilee, and employees learn, work and live together. Like ISCAR, Tefen integrated Galilee’s diverse population and rallied them around a universal goal: Profit.

Wertheimer has now built six industrial parks: Five in Israel and one in Turkey. Nazareth will be the seventh. Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s first native-born prime minister and the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, said of the project: “With 20 more industrial parks like these, it would be possible to double the industrial export output of Israel. This would completely change the economic, social and security situation.”

Wertheimer wanted to test the effectiveness of his model beyond Israel. In 2005 he built a park in Gebze, outside Istanbul, and partnered with Turkish universities to pull entrepreneurs to the park. As was the case with Tefen, a newly unveiled “Technopark” law provided tax advantages for the project. It has been a success thus far, adding to Wertheimer’s roster of winning startups and sales/employee figures, but increasingly tenuous relations between Israel and Turkey could change that. Those strains are in part a by-product of the 2010 dispute over the Gaza flotilla. They’ve been worsened by a prolonged ownership dispute between Turkey and Israel over the Leviathan gas field in the Mediterranean. Former billionaire Michael Federmann has already suffered the consequences of these tensions. His security company, Elbit Systems, was forced by Israel’s Ministry of Defense to cancel a contract with the Turkish air force, a reversal expected to cost Elbit $60 million in net profit. Wertheimer is quietly nervous about the future.

Wertheimer has had at least one other setback to date. He had drawn up plans in the early 2000s to bring a park to Rafah, a poor Gaza town, but increased violence in 2002 as the Second Intifada heated up prevented him from taking the risk. He still has hopes the Rafah park will one day become a reality.

Wertheimer’s efforts have won him dozens of awards. Not that he likes to talk about them. When asked, he brushes the question aside. “This is a story about the industrial parks,” he says, curtly.

Wertheimer won’t venture a guess as to when, how or even if the Arab-Israeli conflict will draw to a conclusion. There are too many competing interests, too many leaders on both sides who gain power through the tension, too few resources allocated in the right places. Against all that, even Wertheimer is humbled.

“Please help me,” he asks, “by not forgetting this story.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)