The foreign edge to Bollywood

For foreign technicians, geographical lines have blurred as they answer the call of Indian movies

Cinematographer Nikos Andritsakis doesn’t remember what or who he was filming on his first ever shoot in India, but he vividly recalls how he felt—overwhelmed. “I had never seen so many people on a set before. Everyone was waiting for me to set up. Just the sheer size of an Indian crew can be staggering,” says Andritsakis. This was eight years ago. Since then, the 39-year-old Greek cameraman has shot numerous commercials and five feature-length films, including Shanghai (2012) and Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! (2015).

In the last decade, actors like Katrina Kaif, Nargis Fakhri and Jacqueline Fernandez ‘crossed over’ into India seeking fame and fortune. But behind-the-scenes too, Bollywood’s expatriate community, of which Andritsakis is a part, is growing, and includes musicians, hair and make-up stylists and cinematographers. Their stamp is visible in the increasingly refined final look-and-feel of Indian movies.

This influx of international professionals is not surprising. As the largest film industry in the world, it is natural for Bollywood to attract talent from all over. “Indian films are creating a buzz on the festival circuit. People are looking towards India and indie films here with interest,” says British violist and composer Benedict Taylor, 34, who has scored for films like Anurag Kashyap’s The Girl in Yellow Boots (2011) and Anand Gandhi’s Ship of Theseus (2013). “Everyone wants to work with good talent and it doesn’t matter what your nationality is. If they want to come and work with us, it means that our industry is becoming bigger and more lucrative. Look at Hollywood; almost half their talent—both in front of and behind the camera is foreign,” says actor Anil Kapoor who, apart from being part of international projects (TV show 24, Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire, among others), has worked with multiple foreign technicians in Bollywood too. In 2007, for Gandhi My Father, a film that he produced, Kapoor hired David McDonald, a British cinematographer.

The man behind the camera in the 2015 hit Dil Dhadakne Do, in which Kapoor was part of the ensemble cast, was also a foreigner—the Spaniard Carlos Catalan. The cinematographer, who has shot with the likes of Benedict Cumberbatch (Third Star, 2010) and Martin Freeman (The Eichmann Show, 2015), first came to India to shoot Zoya Akhtar’s debut film Luck By Chance (2009). Catalan has since become a regular part of her crew. “International DoPs (directors of photography) come with a different perspective. They look at India with a fresh eye. It’s the same as when an Indian cinematographer would shoot New York—you will get a different look, framing and colour,” says Kapoor.

You can see it in Dibakar Banerjee’s Love, Sex Aur Dhokha (2010). When the director was putting together his crew, he was looking for a DoP who had shot extensively in the digital format. He was introduced to Andritsakis, a star student from London Film School, who had come to India to shoot a movie that was eventually shelved. Andritsakis fulfilled Banerjee’s criteria of someone who could work with a small crew, a tight budget and shoot on digital.

Banerjee and Andritsakis have become regular collaborators since, having made three films together, including period noir Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!. “We come from very different cultural backgrounds and that’s what we bring to the table. If there are differences in understanding and aesthetics, it sparks a debate and that fuels our creative process. It’s been an interesting creative journey of growth for both of us,” says Andritsakis.

Several other long-term partnerships have developed between foreign technicians and Indian filmmakers, including the one between director Prakash Jha and composer Wayne Sharpe. The 59-year-old New Yorker has not only created music for four films directed and produced by Jha, but has also had a one-dialogue role as an American journalist in Gangaajal (2003). “He said I should stick to music and never act again,” Sharpe says, laughing at the memory. Even before he met Jha, however, Sharpe had wanted to work in Bollywood. “Taal was the first Bollywood film I ever saw. I was completely blown away by the music and the effect it had on the film.” The composer has gone on to win the 2004 Filmfare Award for Best Background Score for Gangaajal.

Sharpe draws on over three decades of classical music training to deliver a blend of “Indian music with Western scoring practice”. For the much-acclaimed indie sports film Lahore (2010), Sharpe roped in vocalist Lisbeth Scott (who features on the soundtracks for The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (2005), The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (2008) and Munich (2005), among others) to sing “the film’s main theme in a made-up language”. “That kind of set the mood for the rest of the score. As an American, it was a challenge to completely immerse myself into the art and culture of India and create music that would be welcomed by the Indian people,” says Sharpe in an email interview.

Every Indian film starts with what Sharpe calls the ‘spotting process’. “The director and I go through the entire film scene-by-scene. He will thoroughly explain the meaning, the background and emotional centre of each scene. This is where any cultural differences or understanding are sorted out.” Sharpe composes a majority of the music in New York, where he is based, and then records with Indian musicians here.

Benedict Taylor has composed music for several Indian films

Like Sharpe, Benedict Taylor, who was born in Kendal, a small market town in England’s picturesque Lake District, is also a classically trained composer. He first came to India in 2007 for an academic year residency at the Mehli Mehta Music Foundation in Mumbai. It was during this period that Taylor was introduced by friends to actor-composer Naren Chandavarkar. The duo has since composed for award-winning indie films like Ship of Theseus and Killa (2015). “The kind of music I do here is very close to the compositions that I do in London. A lot of music that I have created is heavily linked to European avant-garde in the style of creation,” says Taylor.

While he is very aware of the distinctions between Indian and Western music, Taylor doesn’t overly dwell on it. “If you create music without worrying about geography, then music is just music,” he says. Taylor, who is married to actor Radhika Apte, splits time between Mumbai and London. “As an independent artiste, you can be in two places at the same time. Right now I am working in London on a composition for a theatre piece and, at the same time, I am working with my colleagues in Mumbai. All I need is good internet,” he laughs.

Another expat, who found both work and love in India, is self-taught London-bred cinematographer Jason West. In the 12 years West has been working in India, he has shot three films—Rock On!! (2008), Delhi Belly (2011) and Don 2 (2011)—and married singer Suneeta Rao. The couple, along with their seven-year-old daughter Maya, call Mumbai home. “I have never felt like an outsider and language has never been a barrier. They give me the script in English and I speak a little bit of Hindi now. I can tell if someone is not being nice, regardless of the language!” he says.

It is obviously not as easy for everyone. Take the case of Polish cinematographer Pawel Dyllus. While he enjoyed working with the cast and crew of the yet-to-be-released Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Mirzya (2016), Dyllus says the first few days of being in India were tough on him. “No one talks about this too much, but when you’re working abroad, loneliness is a big problem. You are in the other end of the world, and completely alone. You know you’re about to spend the next half-a-year there. It takes a while to adjust to new conditions,” says the 34-year-old.

It was his work on the multi-award winning-Polish film Life Feels Good (2013) by Maciej Pieprzyca that got international filmmakers interested in working with Dyllus. Apart from Mirzya, his earlier experience of working outside his native Poland was in Armenia where he shot Bari Luys (2015). “Between 2013 and 2015, I barely spent four months in Poland. I was either in Armenia or in India,” says Dyllus, in an email interview from Warsaw.

Much like everything else here, the crews on set are also larger-than-life, a fact that cinematographers who come to work in India are constantly amazed by. “There are more people on the set here than anywhere else I have worked. There are attendants to look after the camera! They don’t necessarily do anything much. If I have an entire crew of 30 here, in Germany, I would have with 8-9 people,” says West. “But now I understand how it works. It’s just a slightly different beast from elsewhere.”

The beast has been figured out by most, though. For instance, Daniel Bauer, who has been in India for seven years now, was the make-up and hair stylist during the promotion tour for Fitoor (2016), during which he worked with Katrina Kaif. As Kaif did multiple television interviews at Mehboob Studio in Mumbai, Bauer kept an eye on the monitors even as his assistant touched up her make-up. He got what was needed, perhaps better than most. It helps that Bollywood was an integral part of Bauer’s childhood in Germany. “I come from a very mixed family. My dad is German, mom is Thai, my grandfather was Indian and my grandmother was Chinese. Growing up in a very Asian household in Germany, Bollywood was as big as Hollywood. I knew Amitabh Bachchan as well as Clint Eastwood,” say the 39-year-old, who Vogue India named the make-up artist of 2015.

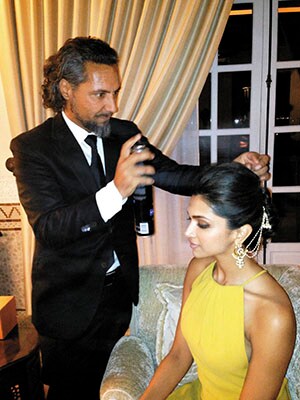

On the other hand, there is Gabriel Georgiou, an Australia born of Greek heritage, who knew very little about Bollywood when he first came to India on a hair-styling assignment way back in 2008. “I don’t think I had seen any films. I just knew there was a lot of song and dance,” he says. Since then, he’s been an integral part of films like Bajirao Mastani (2015), Tamasha (2015), Bombay Velvet (2015) and Jab Tak Hai Jaan (2012).

Georgiou came to India with a strong portfolio, for both film and fashion. “I had worked in Hollywood with names like Drew Barrymore, Jessica Alba, Cate Blanchett and Robert Downey Jr. I came to Mumbai to do photoshoots for a fashion magazine and then came the ads and eventually movies,” says Georgiou. While he’s worked with all the A-list actresses in Bollywood, Georgiou collaborates most regularly with Anushka Sharma and Deepika Padukone.

Both Georgiou and Bauer are now primarily based in Mumbai though they continue to shoot internationally. After spending the initial months in their respective agency’s ‘artist homes’, both of them now rent apartments in suburban Mumbai. “I shared the artist home with some models from Europe and Australia. They were my initial support group in the city. People in our business are so social that over the years, I have made a lot of friends in the city,” adds Bauer.

One of the concepts they learn early is jugaad (the Indian quick-fix). “I love how efficiently and quickly people improvise and solve problems here. Everywhere else, people have specialisations and that’s what they would do on the set. But in India, everyone is ready to pitch in. Indian crews are very passionate and committed to making movies,” says Andritsakis. His earliest memory of jugaad involved a waterproof casing for his camera. “We had a really tiny camera and the regular casing wasn’t fitting. So they made one out of tin that worked just as well and cost a fraction.”

Then there was Bauer’s first encounter with a jugaad smoke machine (“burning charcoal with incense powder thrown to create smoke”), which had him ready to evacuate the studio in Film City. “But I am now so used to it, I don’t even look twice,” he says.

The bonhomie and easy integration with the work, however, cannot hide the thorns in the seemingly rosy welcome carpet for expats. The Western Indian Cinematographers’ Association (WICA) has for long been protesting against foreign cinematographers who, they claim, do not have valid work permits. In 2014, members of the Cine Costume & Make-up Artist & Hair Dressers Association even showed up on the sets of Kabir Khan’s Phantom (2015) to protest against Bauer working on the film.

Understandably, most of the technicians ForbesLife India spoke with chose not to comment on this issue. Andritsakis, however, did say this: “I have never had a problem with the unions. The Indian government has a way of filtering and the unions should respect that. Unions perpetuate the myth that there is a lack of work because of non-locals. That’s not true. There’s enough work for everyone. People should be able to hire talent they want to work with.”

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra wonders what the fuss is all about. “When this industry started, we had British and German technicians editing [films] and behind the camera. As the world gets smaller, you will all kinds of talent travelling to where interesting work is happening,” says Mehra.

Anil Kapoor points out that “there’s a tendency in Bollywood to be insecure about working with foreigners”. The actor says, “I think we need to be more secure in our talent and abilities. We should be able to push ourselves to become better.” After all, with ‘crossing over’ to Hollywood becoming a status symbol of sorts, why should different rules apply to a reverse flow of talent? Especially when Indian cinema is the clear beneficiary.

(This story appears in the May-June 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)