'If you learn by praise, you're going to do bad work'

From Tumhari Amrita to Mughal-e-Azam, theatre director Feroz Abbas Khan has journeyed from minimalist to opulence

Image: Joshua Navalkar

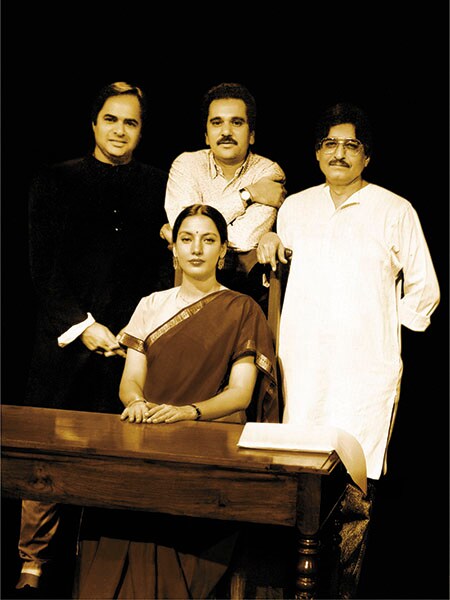

Back in 1992, theatre director and writer Feroz Abbas Khan had staged a final dress rehearsal for his play Tumhari Amrita a day before he was opening it up to audiences. This was Khan’s tribute to the late veteran theatre actor Jennifer Kapoor, and was to be staged at the Prithvhi Theatre founded by her in Juhu, Mumbai.

It was not meant to run for more than four shows.

A tale of unrequited love between the protagonists, Amrita Nigam and Zulfikar Haider, told through the letters they wrote to each other over decades, it was an adaptation of AR Gurney’s Love Letters. Essaying the roles of Amrita and Zulfikar were the serious acting chops of Shabana Azmi and Farooq Sheikh. And yet, as they sat there reading letters to each other over an hour-and-a-half, six of the eight technicians present at the theatre were lulled into slumber out of utter boredom. “I’ve never been so depressed and petrified. I got very upset with Shabana and Farooq,” Khan, 57, tells ForbesLife India.

There wasn’t much he could do at that nth hour apart from making a few cosmetic changes. For one, instead of having the actors sit on either side of one table, he placed them at different tables. For the other, he decided to make an appearance on stage before the play to ease the audience into the experience. “It just helped to settle them down. I had to prepare them and let them know that ‘this is what the play is about so don’t expect anything else’,” says Khan.

Tumhari Amrita went on to become a life-changing experience for Khan. It ran for 21 years and was staged across the world, including countries like Norway, coming to a close only after Farooq Sheikh’s demise in 2013.

“This [the success] tells you that the audience is far ahead of your friends,” he laughs. At the same time, this experience also made Khan value criticism more dearly. “If you learn by praise, you’re going to do bad work most of the time. Let there be intense criticism. I’m a huge critic of my own work. When I did Dinner with Friends (2011; play written by Donald Margulies), I couldn’t sleep because it wasn’t holding my attention. The audience is far more generous than I am.”

He still hasn’t solved the mystery behind Tumhari Amrita’s resounding success. “It was an accident,” he offers.

Not quite.

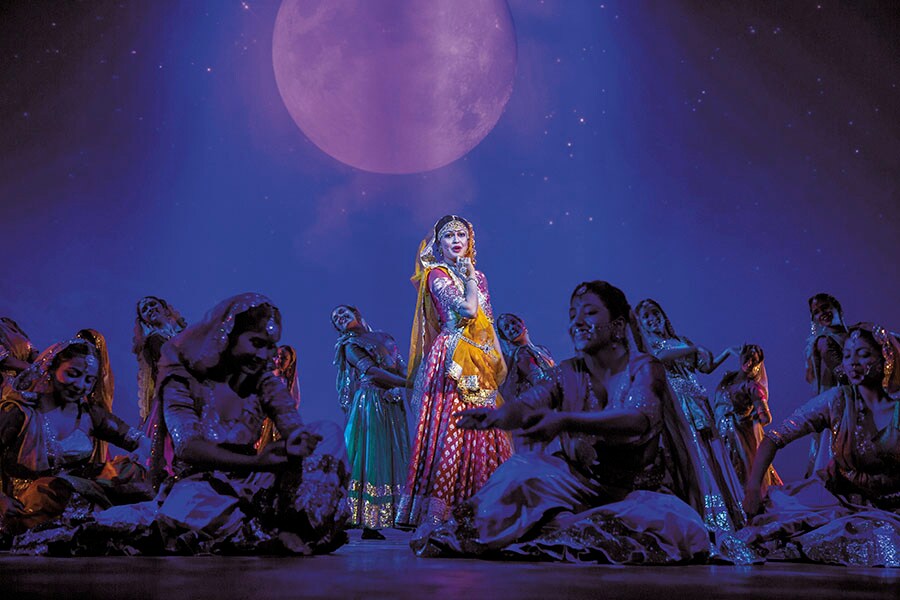

When ForbesLife India met Khan in October, he was in the midst of yet another crucial dress rehearsal. But this time, the stakes were higher. Instead of just two actors, he had a cast and crew of about 70 people waiting for him. And as opposed to the two simple wooden tables of Tumhari Amrita, he had an army working on erecting a spectacular backdrop of a Mughal-era palace. “Doing something you haven’t done and feeling that this might not happen is the challenge. Before starting a play, I always ask myself—does this come easily to me? If the answer is yes, then I shouldn’t make it. It should be tough,” he says.

This explains why he took on the audacious task of bringing the iconic celluloid love story, Mughal-e-Azam, to stage. “I’m going against my grain with this one,” he says. Though Khan has directed large-scale productions like Mahatma vs Gandhi (1998) and the Gujarati musical Eva Mumbai Ma Chaal Jaiye (1991), his oeuvre is predominantly “minimalist”—a word that doesn’t fit well with the epic scale of a Mughal-e-Azam. “The thing that is intrinsically linked with Mughal-e-Azam is scale and its larger-than-life production. Having said that, I’ve tried not to lose the intimacy because, in the end, people come for the story,” he says. “But Mughal-e-Azam is a story on steroids. I feel like I’m starting my career all over again.”

The other hurdle in refashioning a classic is that viewers are, often, too emotionally attached to the original. In Indian cinema, the image of Madhubala as Anarkali defiantly asking ‘Pyar Kiya to Darna Kya?’ is an enduring one. Imagine attempting to recreate that moment with another actor.

Though K Asif’s film released in 1960, legendary tales about its 10-year-long creation, its performances and signature dialogues have been passed down over generations. Khan hasn’t lost sight of the richness of this legacy. “There are strong memories attached to this story. Children may not have seen the film, but they have heard their parents talk about it. That needed to be understood and respected,” he says. In fact, the performance kicks off with an emotional audio clip by Lata Mangeshkar—whose rendition of the film’s immortal songs, ‘Pyar Kiya to Darna Kya’ to name just one, is unforgettable—reminiscing her time with legendary composer Naushad. Her familiar voice reverberating through the theatre is comforting and immediately transports you to another era.

In April 2013, Khan gave an interview to The New York Times where he was asked why Indian productions couldn’t match the scale of musicals in Broadway or the West End in London. “In India, we do not have any performance spaces to accommodate the technical wizardry of these musicals,” he explained. “We do have the talent and stories but we need the infrastructure and finances to achieve the quality of Broadway productions.”

Image: Joshua Navalkar

Surprisingly, in just three years, Khan has managed to overcome these shortcomings. As he walks out of the National Centre for the Performing Arts’ (NCPA) Jamshed Bhabha auditorium five days before his premiere, he points out that doing technical rehearsals so many days before the real show may be passé for Broadway, but it is nothing short of a luxury for Indian theatre directors. “Even to look at the Jamshed Bhabha auditorium is an expensive proposition,” he laughs.

It took two partners to join forces for Khan to garner adequate resources for a production of this scale. The NCPA had, for a while, expressed their desire to work with Khan so he had them on board. And when Khan visited business group Shapoorji Pallonji—the producers of the film—for staging rights, they immediately offered to be co-producers on this too. Though he doesn’t divulge any numbers, Mughal-e-Azam is rumoured to be the most expensive stage production to have ever come out of India. Consider that he’s had around 30 dancers from around the country shift base to Mumbai for about two months to rehearse. Foreign crew members have been flown down to work on this project too. Bollywood casting director Mukesh Chhabra went through months of auditions to find actors who could sing live on stage, dance, as well as act. And designer Manish Malhotra laboured over the costumes to add to the glamour and grandeur of the production.

Luckily for Khan, it didn’t take too long for his hard work to pay off. Less than a week after its premiere on October 21, he had to announce extra shows on public demand. Those too sold out in no time.

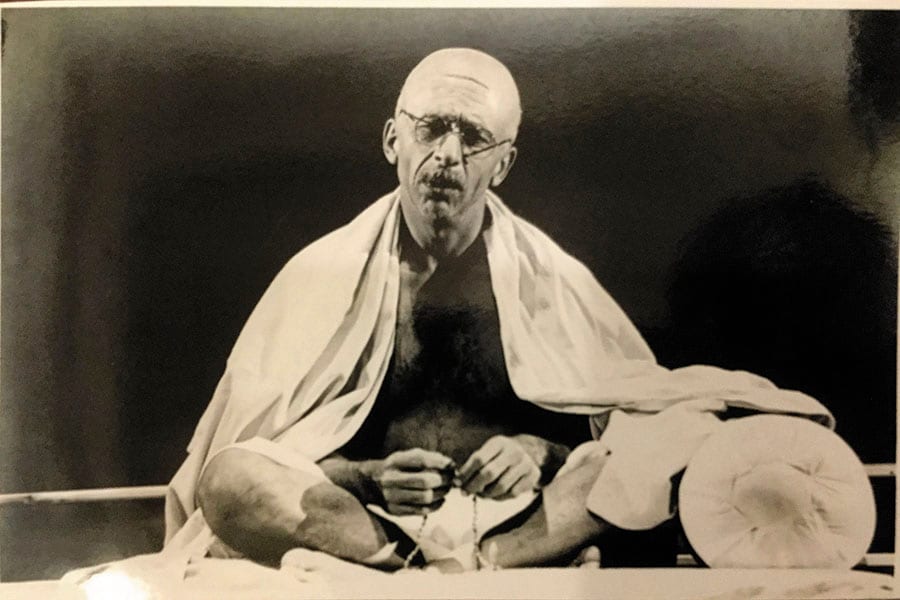

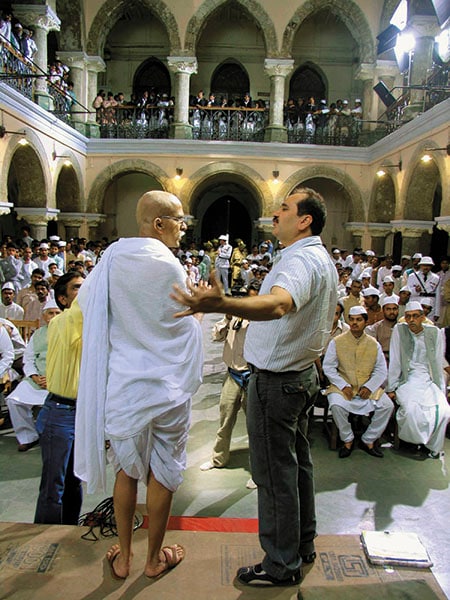

Khan is no stranger to success. He knows what it tastes like. Rarely has his play opened to scathing reviews or struggled to find an audience. His Mahatma vs Gandhi was famously reviewed as “the finest English play to emerge from India for a very long time” by The New York Times. That said, the acceptance of Mughal-e-Azam may offer him a different kind of high as a creator. As Khan himself confesses, this has been his least personal work to date.

Take Kuchh Bhi Ho Sakta Hai, a two-and-a-half-hour solo performance by Anupam Kher that centres around the actor’s personal and professional upheavals. Or Mahatma vs Gandhi, which forces you to look beyond the man’s greatness by throwing light on his failures as a father and a husband. Salesman Ramlal too—an Indian adaptation of Arthur Miller’s classic Death of a Salesman—tells the moving tale of an honest salesman struggling to pay bills and run a household in the twilight of his career. All of Khan’s works are strongly rooted in reality and deal with some uncomfortable truths. “I’m inspired by extraordinary people and life itself. There are hard truths in my work that come from a very personal space. Also, my plays have a strong contemporary connection, so they don’t date. Maybe that’s why they all carry on for a couple of years,” says Khan. “Mughal-e-Azam, on the other hand, is very different. This is my tribute to a classic.”

Khan has also dabbled in cinema, but his repertoire in that department pales in comparison to his achievements in theatre. His first film Gandhi, My Father (2007) was a thematic extension of his play Mahatma vs Gandhi. Produced by Anil Kapoor, the film was well-received critically. His second film Dekh Tamasha Dekh which released in 2014 is a political satire that hardly made much of a noise. “I’m very proud of both of my films,” he says. “I can probably find people who will want me to make films for them, but that part where it reaches a wide audience is a puzzle I haven’t solved as yet. Then what’s the point of making it? I rather do theatre —I’ve got that audience with me. I get a sense that cinema would be primarily entertainment. I guess the same person watches cinema for entertainment and watches theatre for more than entertainment.”

Khan’s first film Gandhi, My Father was critically acclaimed

His tryst with Bollywood is also marked by a comedy of errors caused by the name he shared with the late Feroz Khan. After a series of hilarious misunderstandings, he decided to add a middle name ‘Abbas’ to stand apart from the Bollywood actor-director.

“Unfortunately he passed away soon after I changed my name. It caused a huge confusion. I remember when his son was arrested for buying drugs, I used to get calls of sympathy. When I would travel abroad for Tumhari Amrita, I realised the NRIs only knew film stars. So at the end of the play when they called me on stage, people were cheering. But when I entered, there was silence. I had disappointed them so much,” he recalls, cracking up with laughter. “It was all so funny. And then one day I got a call from Sanjay Khan’s office asking for his brother and that I thought was the ultimate goof-up!”

These misadventures aside, Khan says he will certainly try his hand at filmmaking again. But for now, he has his hands full with his latest baby. He’ll go to Delhi early next year with Mughal-e-Azam and then see if other auditoriums in India can handle the requirements of his production. Eventually, it will travel abroad like his other plays.

There is, however, no concrete decision yet about the countries that he intends to go to.

“I feel like I’m giving birth to a child. And you fear for your child. Will it be fine? How will things affect the health of the child? How will they affect your health? Because whatever happens to your child is going to affect you,” he says, before rushing into yet another daunting rehearsal.

(This story appears in the Nov-Dec 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X