Tulip Telecom Gears Up for a Big Fight

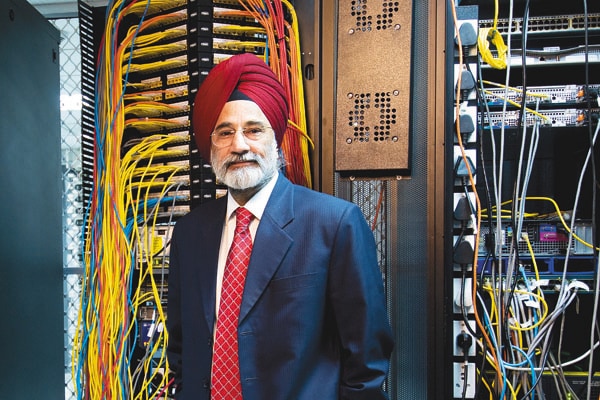

H.S. Bedi’s Tulip Telecom became a success by targeting places too small for its larger competitors. It now wants to take the fight right to their doorsteps

No matter which corner of the earth you go to, you’ll be sure to find a “Gulf”-crazy Malayali. Legend has it that Messrs Armstrong and Aldrin stepped right off their Apollo 11 spacecraft in 1969 only to find a Malayali running a tea shop, on the moon. And in 2003 it was Malayalis who helped a retired Sikh Army colonel discover the sweet spot for his business, turning Tulip Telecom into one of the best success stories of Indian telecom.

Okay, maybe the first line was an exaggeration, and the second an unsubstantiated rumour. But Malayalis have indeed played a crucial role in helping Col. H.S Bedi’s company reach nearly Rs. 2,000 crore in revenue, in the process handsomely beating biggies like Bharti-Airtel, Tata Communications and Reliance Communications on the stock market. Over a five-year period Tulip’s stock is up 394 percent, versus Bharti-Airtel’s at 76 percent and both Reliance Comm’s and Tata Comm’s showing negative returns. In the last one year alone Tulip shares are up 141 percent while those of the other three are either flat or negative.

But Tulip Telecom wasn’t always this sexy. It started out in Delhi in 1991 reselling floppy discs. Bedi joined Tulip in 1993 after retiring early from the Indian Army, where he helped pilot one of the largest IT deployments in the country. By 1995 Tulip was reselling computer software; in a few years it switched to selling personal computers. By 1997 Bedi had bought out the original founders, his mother-in-law and a friend. By 1999 Tulip was selling networking equipment. By the end of the decade it was helping businesses with multiple offices in a 50 km radius link them up using wireless networking. “Markets invariably get commoditised, and after that you can only do so well. The only option was to constantly innovate,” says Bedi.

Then, in 2003 the Malayalis called.

Look Ma, No Wires!

The district of Malappuram, a hilly 3,500-square km area with roughly 3.5 million inhabitants, wanted to become the first district in the country to become “100 percent computer-literate”. They intended to do so through “Project Akshaya”, a government-led initiative to put up hundreds of Internet-connected village centres, where people could email, surf, or learn basic computer skills.

But most of the villages didn’t have a wired telephone connection at the centres; and the vast and hilly terrain made it expensive to lay additional cable. The solution — going wireless — became Tulip’s market opportunity. In 2003 it won the contract to put up a wireless radio network linking the various village centres. It was a challenging project for a company unused to such scale. At times it faced severe cash flow issues, but got support from understanding government representatives who loaned it Rs. 2.5 crore in advances.

By the time Tulip was done with the Malappuram wireless project, it had gained crucial first-hand knowledge of two things: The vast market opportunity in wirelessly connecting smaller towns and cities, and the technical ability to design and build cost-effective networks.

Alok Shende of Ascentius, a telecom consulting firm, calls the people at Tulip a bunch of “very savvy opportunists”. He says, “Tulip has capitalised on certain white spaces in the market. For instance the enterprise data market was traditionally a top-down one, with the early movers targeting large companies. Mid-market customers were not being addressed, which Tulip did a phenomenal job of. There was a clear opportunity, and they rode the wave.”

Tulip’s decision to target enterprise customers from the bottom-up (technically more like the middle-up) had another advantage: It faced very little competition. So, it signed up customers at a fast rate, didn’t face as much competitive pressure on pricing and most importantly, it remained off the radar of bigger players.

It achieved scale in a relatively short time — over 1,300 customers across 1,500 cities, nearly Rs. 500 crore in sales every quarter and a number five position in the Indian enterprise data segment with an overall market share of 11.3 percent (just 3-4 percent less than the next three players Bharti-Airtel, Reliance and BSNL. Tata Comm with a 23 percent marketshare is the clear leader).

“We took the game from 10 cities to 1,500 cities, changing the rules of the game,” says Bedi. He is right, because in many ways Tulip’s wireless last mile network, which he claims is the largest in India, is like the mass-market distribution reach of a consumer goods company like Unilever. While his larger competitors were investing in expensive submarine cables and national fibre networks to carry huge amounts of data within and outside India, Bedi was putting in place the last mile infrastructure to sell it to customers.

And yet his business almost came to a standstill in 2005, when the Indian government imposed a license fee of Rs. 10 crore on telecom companies that wanted to offer virtual private network (VPN) services to customers. VPNs are secure computer networks created atop public communication infrastructure. For many businesses it is a cost-effective way to create a private communication line between its offices. According to research firm Frost & Sullivan, the VPN market at 36 percent forms one of the biggest chunks of the Indian enterprise data services market. And wireless VPN customers are the mainstay of Tulip’s revenue.

“I didn’t have the fee money, and even after pitching to many investors, no one was willing to [invest],” says Bedi.

Fortunately things changed. Intel’s venture capital arm along with a few other funds offered Rs. 40 crore in return for a 40 percent stake in the business. Then Yes Bank offered an alternative — Rs. 30 crore in debt. But ultimately Bedi decided to try his luck with the stock market. He filed for an IPO and in December 2005 managed to sell 30 percent of his company to investors for Rs. 105 crore. The general public had valued Tulip 3.5 times more dearly than veteran technology investors.

Now that he has proved that wireless connectivity was an immensely profitable opportunity, Bedi wants to move on. “A year back we decided that wireless, with its limited capability, could only take us so far.” His new big bet is fibre.

Plug Me Up, Scotty!

For telecom operators, underground optical fibre cable is the preferred choice for carrying large amounts of data in big cities. Thousands of kilometres of underground fibre optic cables criss-cross most of India’s cities and towns. But none of it belonged to Tulip, so it was forced to lease capacity on these cables — in most cases from its larger competitors.

The company has therefore embarked on a staggered plan to lay its own cables in the central business districts (CBDs) of the 100 biggest cities in India. Interestingly, Tulip is only planning to lay last-mile cables to CBD offices in these cities.

“With our own fibre we can now offer high bandwidth data services,” says Bedi. Compared to average speeds of 64-128 Kbps for its wireless customers, Tulip now hopes to serve its fibre customers average speeds of 2-5 Mbps — 20 to 40 times more than earlier. Notwithstanding its contrarian customer segmenting approach till date, large enterprises in big cities is a market Tulip cannot afford to ignore — it claims 69 percent of the data services market is made up of large enterprises, many of which have offices in big city CBDs.

By laying its own cables and expanding its offerings, Tulip says it can increase its addressable market from 18 percent to 89 percent of the Rs. 6,051 crore Indian enterprise data services market. “In three years we want to change our revenue split between wireless and fibre from 100:0 to 70:30 to 30:70,” adds Bedi.

Nareshchandra Singh, a telecom analyst with Gartner says, “CBDs are the crowded but low-hanging fruit, and almost everyone will be present there. But for a company like Tulip that may still be the only choice if they want to be an end to end player. Otherwise they may remain a secondary player catering to those needs when nothing else is available.”

Bedi is hoping to elevate Tulip into the list of Tier-1 competitors like Bharti, Reliance and Tata. He has the requisite regulatory licenses (VPN, ISP, NLD and ILD), the customer base (Tulip claims between 70 to 80 percent of the top 500 Indian businesses buy some of its services) and the technical know-how. What was missing was a wired last mile.

But laying fibre optic cable to commercial districts is a strategy being followed by many other operators, including ISPs, says Shende. He calls this fibre-laying binge the “Balkanisation” of the data market, saying, “Like in the cable TV industry, service providers are carving out and claiming for themselves even places like Kandivili or Thane in Mumbai. Because once you have a pipe to the customer’s door, it is very hard for someone to dislodge you.”

But Tulip may not even be aiming to dislodge, says Nanditha Krishna, an analyst with Frost & Sullivan: “The Indian enterprise data market is just starting to mature, and the next level of networking demand will come from redundancy. You will see Tulip going in as a secondary operator, either being used to supplement the customer’s primary bandwidth supply or to act as a backup option.”

If Krishna is right, that may be Tulip’s best bet to move up the data value chain than going head to head against its larger competitors — as they can bundle consumer products (mobile, fixed line and broadband) alongside every conceivable enterprise offering in order to sweeten the deal for customers. They also own most of their infrastructure, giving them more control over service levels and pricing.

Shende says, “Though upselling to their existing customers for a greater share of wallet is a good strategy, Tulip will still be entering markets that are more commoditised and where prices drop much more rapidly. It will find itself sandwiched between lots of competition — cheaper prices on one end and more extensive solutions on the other.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)