Ready to Germinate

The boffins who left biotech firm Monsanto in 2001 are now ready to take it on

K.K. Narayanan was stunned. “Why do you need VC money? Instead pledge your cars or wives’ jewellery, like we did at Infosys,” he was told. And Narayanan thought that N.S. Raghavan, one of the co-founders, of Infosys, would understand a bunch of bright biotech scientists.

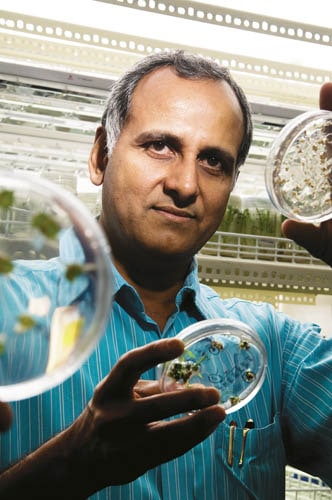

Narayanan and his colleagues — Gautham Nadig and Ganesh Kishore — persisted and Raghavan gave them Rs. 6.5 crore to start Metahelix, an agricultural biotech company, in 2001. “I made a gut call based on their qualifications and experience at Monsanto,” says Raghavan. He might as well add ambition to that quality.

After eight years Metahelix is ready to compete and guess who is on the other side of the net? The big daddy of genetically modified seeds, Monsanto. This is the moment of truth for Raghavan’s gut and Narayanan’s execution.

The Rs. 7,000 crore Indian market for agricultural seeds is the fifth largest in the world. Of that, roughly Rs. 2,000 crore is the market for cotton seeds. This is the market Metahelix is targetting. Nadig says a 10 percent market share is what Metahelix will be gunning for in the next three to five years.

Based on today’s market and prices, that would mean Rs. 200 crore in revenue.

Over 90 percent of Metahelix’s target market is transgenic, or genetically modified (GM). And 95 percent of those seeds contain technology from one company — Monsanto. Monsanto is the Coca-Cola of GM seeds business.

Based on proprietary genes derived from the Bacillus Thuringiensis (Bt.) bacteria, Monsanto makes the “secret sauce” or the “concentrate” that makes a seed resistant to bollworms and armyworms, both nasty vermins. It licences the “concentrate” to companies like Rasi, Nuziveedu, Ankur, and Mahyco that are like the local bottling company of Coca Cola. These guys add other features like usage of water, fast breeding time (based on local farmers’ needs) to the concentrate and then handle the distribution and selling of the seed to the farmers.

For example, a hybrid for Andhra Pradesh’s (AP) Telengana district will make do with lesser water (the area is mostly rain-fed), fertilizer (most farmers are poor) while maturing faster (poor farmers prefer quicker yields). In comparison, the hybrid for AP’s coastal districts will mature slower (so they have time to absorb the nutrients over time) and offer better yields (most farmers are rich, and their plots are irrigated).

That’s why even though there are only five commercial Bt. variants in the country (two from Monsanto, one each from JK, Nath and Metahelix), there are over 300 different branded cotton hybrids that are sold. Almost all of these contain the Bt. gene — Monsanto’s in over 90 percent cases — but the variety is in the hybrid features, the localisation as it were.

A Masterstroke

If Metahelix has to take on Monsanto then the battle is clearly split in two phases. The first phase is to come up with a “concentrate” that can rival Monsanto’s. This it has done. It is the first company globally to isolate and use a completely new Bt. gene segment, cry1C, in cotton seed.

Metahelix’s new seed offers protection against both the Lepidoptera and Spodoptera pest families, placing it on a strong footing against first generation Bt. cotton seeds which target only the former pest family.

Metahelix’s seeds have undergone a stringent series of trials across India since 2005. In July, two of Metahelix’s Bt. cotton seeds, 5125Bt and 5174Bt, received official approval for commercial use in central and south India. But the approval was too late for this year’s kharif sowing season.

Conventionally, the way Indian scientist-backed start-ups behave, now would be the time for nerds to give way to the suits who would start looking for distribution tie-ups. Metahelix doesn’t have to do that.

Why? Because it already has a distribution company called Dhaanya Seeds. Dhaanya Seeds is a commercial masterstroke. From a Rs. 3 crore turnover in 2003 the company is now Rs. 80 crore in turnover. It sells “normal” non-Bt. seeds for rice, sunflower, tomato and brinjal.

Dhaanya has provided Metahelix with two strong advantages. It has created the distribution platform for the company’s Bt. cotton seed now that it is ready to be sold. It also provides a steady stream of money to fund R&D. This is where the business acumen of this team shows through.

The Differentiator

When Metahelix started, it needed money to fund its research and clearly angel funding was not enough. So the company started doing contract research — research for other companies. This brought in the cash but diverted company resources away from their own seed research programme. One of the first people to spot this shift was N.S. Raghavan.

“In the early days of outsourcing, we at Infosys refused to agree to GE’s conditions that all the code we generated would be theirs. Even as all other vendors agreed we stood our ground, because we felt that owning some elements of the code was critical for us to build a more robust, re-usable delivery platform,” says Raghavan.

But doing away with contract research meant Metahelix would need to find an alternate revenue source, so that its R&D would not suffer. That’s why Dhaanya Seeds was created. The cash-flow from Dhaanya allowed Metahelix scientists to concentrate on their own R&D. That bore fruit when they became the first company in the world to isolate and use a completely new Bt. gene segment, cry1C, in the cotton seed.

So Metahelix has the product and the distribution. Still, that may not be sufficient. When they do enter the market, gone will be the low-hanging fruit of converting non-Bt. farmers to Bt. ones. That battle is already over, for Monsanto won it. “The Indian cotton market is almost fully penetrated by Bt. cotton,” says Jagresh Rana, director at Mahyco Monsanto Biotech (MMB), the joint venture between Indian seed company Mahyco and Monsanto which licences the latter’s Bt. cotton in India. “The trend today is farmers shifting from the first to second generation Bt. technologies,” he says.

When that happens, says Nadig, “insect protection will become a given” and therefore cease to be a differentiator. The focus will move to other areas.

“Sometimes in the midst of all these technologies we forget that farmers don’t grow cotton to kill pests, but to get a better yield,” says Narayanan. If Metahelix can engineer a hybrid that can grow faster, utilise nutrient-s more effectively or produce a better yield, that might be its differentiator. This opinion is shared by Suman Sahai, convener of rural advocacy group Gene Campaign. “The success of Bt. cotton in India owes as much to the hybrids developed by Rasi and Nuziveedu, as to Monsanto’s technology. In fact, MMB’s initial seeds which were the first to get government approval were spectacular failures,” she says.

Challenges Ahead

Dhaanya claims that both the cotton hybrids it has developed (5125 for rain-fed areas and 5174 for irrigated areas) have demonstrated better traits like cotton boll size, the length of the fibre (staple) and rejuvenation (ability to withstand longer periods without water) during field trials.

Therefore, when it goes to the market next year, its strategy will be two-pronged: Convince farmers using Bollgard-1 cotton (the first generation of Bt. seeds) to upgrade to Metahelix’s seed which offers added protection against pests, and demonstrate to Bollgard-2 (second generation Bt. seeds) farmers how their hybrid varieties offer better yields while offering the same level of pest protection.

In order to do this it is organising demonstrations of its cotton crops in over 250 locations around the country, where farmers will be allowed to examine Metahelix’s claims through live crops. It is also combining this with village-level meetings where company representatives will explain the benefits of their products over the competition.

“How successful we are in year 1 will depend on the trade channels and our village level demos,” says Ravi Krishna, head of Dhaanya. “But if the crop is successful, then from year 2 onwards each of our original customers will become a reference for added sales.”

Its first year crop will also demonstrate the pest resistance ability vis-à-vis Bollgard-1 and 2. And if it holds up, some seed companies may be tempted to jump ship from Monsanto to Metahelix as the source for the Bt. gene.

“Most seed companies are today aligned with Monsanto, which we may not be able to break immediately,” says Krishna. “Though a few have approached us to sub-licence our technology, we refused. We would prefer to show actual results before tying up with other seed companies.”

And while pest protection may soon become a given, pricing already has. For all practical purposes the price of Bt. cotton is fixed at Rs. 650 (for Bollgard-1) and Rs. 750 (for Bollgard-2) in various states, a matter that Monsanto is fighting in the courts.

This money is shared between Monsanto and the seed companies that licence its technology into their own hybrids. It is here that Metahelix may have an advantage as its cost of developing the Bt. cotton technology is only around a fourth of Monsanto’s. In the immediate term it means Dhaanya will have the freedom to sell at a lower price (though Metahelix says it has not evaluated that decision yet), but more importantly, in the longer term it means Metahelix might be able to offer a lower technology licence fee to other seed companies for its Bt. cotton.

In a volume-led market even a few hundred rupees per packet could alter the equation dramatically. But if Metahelix can convert a few leading seed companies to use its Bt. gene, it might be an added inflection point for the company.

Fact File

The Company: Agricultural biotech company, Metahelix.

The Opportunity: A Rs. 2,000 crore Indian market for cotton seeds

The Target: Capture 10 percent market share over next 3-5 years. That’s Rs. 200 crore in revenue based on today’s market and prices.

Strengths: It has the product — its own version of a genetically modified cotton seed, which is cheaper and offers added protection against pests.

The Challenge: Breaking into a market that is controlled by the world’s largest player in genetically modified seeds, Monsanto.

Bt. Coton Blues

Rapid adoption of genetically modified (GM) seeds has left many environmentalists aghast, as they questioned the long-term effects of GM crops on human health and the environment.

Suman Sahai, the convener of rural advocacy organisation Gene Campaign, says Bt. cotton was “shoved down everyone’s throats” even though there was no clear demand for it. “Not only do GM crops lead to massive buildup of resistance among pests, there is growing evidence that its toxins affect many other organisms than the ones they are targeted at.”

But many leading scientists are questioning that viewpoint. G. Padmanabhan, former director at IISc. Bangalore says, “In India both land and water are limited, so the time has come to make the plant the centre of our focus to ensure adequate yields. But then I see Mahesh Bhatt on TV campaigning against Bt. brinjal, and I realise there is no way we scientists can match that.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)