MakeMyTrip's Tryst with Turbulence and its Journey Ahead

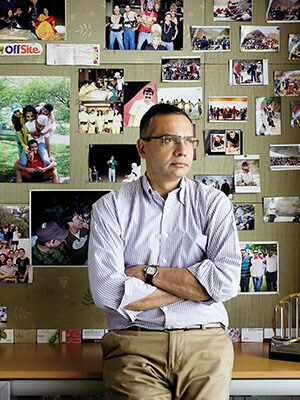

Deep Kalra, Indian online pioneer, has gained and lost his share of altitude. He keeps finding oxygen

In humongous India, where snaking lines and extended waits are emblematic, instant travel reservations herald a new mobility. Deep Kalra’s MakeMyTrip web operation pioneered the online travel field and at times has felt investor and customer delight.

But this is India, remember, and for the 43-year-old Kalra, as for many a service sector startup, the flight has been a bumpy one.

Today MakeMyTrip is fighting to stay profitable in an erratic economy and nascent ecommerce ecosystem. Kalra’s paper wealth, over $50 million, has been halved in 18 months and cut by two-thirds since a post-IPO peak. In the quarter ended in December, MakeMyTrip’s net revenues declined 5.5 percent and losses mounted to $2.6 million.

Even as investors pummeled the stock back to its $14 listing price, Kalra in an interview stoically takes refuge in Bollywood-speak. “Life is QSQT … quarter se quarter tak [quarter to quarter],” he says, using the popular acronym for the iconic romance film Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak.

“We have had plenty of highs and lows,” he recounts. Certainly, the highs have been many. Today one in eight flights within India is booked on MakeMyTrip. In the last four years MakeMyTrip has quintupled revenues, reaching $66.3 million in the first three quarters of fiscal 2013. Profits hit $9 million in fiscal year 2012 before plummeting.

The dips, going back to the company’s founding in 2000, have not always been of Kalra’s doing. India’s economy has skidded badly of late, and its airline industry has gone into a tailspin. In the December quarter domestic air traffic, which accounts for the bulk of MakeMyTrip’s revenues, shrank 9 percent.

“When I look back, we survived a dotcom bust, investor pullout, industry slump, worked for zero salaries and bought out an investor,” says Kalra, a bit wistful. “It has been an incredible voyage.”

By listing on Nasdaq in 2010, MakeMyTrip set itself up to be compared with profitable online retailers in China and elsewhere. Investors have cut Kalra no slack for the singular challenges Indian online retailers face. Take Flipkart, started by former Amazon.com executive Sachin Bansal, which sells everything from books and perfumes to electronics. To overcome marketplace deficits, Bansal set up in-house warehousing and shipping. He even pioneered ‘cash on delivery’ to ease anxiety over online transactions, only to find buyers refusing deliveries at the door. “Even after battling infrastructural challenges, Indian online startups get very little time to build a brand and create customer pull before investors start getting anxious,” said GR Gopinath, who pioneered low-cost flying in India by founding Air Deccan.

MakeMyTrip itself sidestepped the tricky shipping hurdle with electronic check-ins and online hotel vouchers but not assorted other obstacles.

Kalra’s enterprise began in the dusty industrial neighbourhood of Okhla in New Delhi. He had graduated from a premier Indian management school and had short Indian stints at three multinationals but was dissatisfied with corporate life. His eyes were opened to the web’s possibilities when he sold his wife’s car online, making Rs 15,000 more by getting a better price and avoiding a brokerage fee. Then, while booking a holiday to Thailand, he found the hotel was $15 a night cheaper online than the quote by the neighbourhood travel agent. “I was overwhelmed by the feeling that the internet would change the way we lead our lives,” says Kalra. At 31 he set about cutting out the middleman.

His idea found a taker in News Corp-and-Softbank-backed eVentures. Its $2 million was an instant stamp of approval; the term sheet was scribbled on a paper napkin at the Crossroads Mall in Mumbai. The dotcom bubble burst soon after, MakeMyTrip was the last online company to get funded before the dotcom bust, and for the next five years venture capital would not touch online startups. Today MakeMyTrip is the last one left standing among the startups that eVentures pumped millions into before closing down shortly thereafter.

Kalra launched in October 2000 selling tickets and hotel rooms to immigrant Indians travelling back from the US. He outdid mom-and-pop rivals by offering customer support through webchat and a call centre. He interviewed employee number three, co-founder Keyur Joshi, while Joshi was on a train. Their chat was interrupted half a dozen times thanks to a bad connection and a noisy wedding party onboard. Joshi is now the chief commercial officer.

Kalra realised quickly that Indians were looking but not biting online, so he pulled the plug on marketing in India. “It would have been too expensive to catalyse habit change before time,” as he puts it. While competitors burned up cash Kalra tightly focussed his fledgling firm and conserved precious marketing dollars.

The early days were severe. Customer calls would frequently drop in the middle of the night (peak US traffic time) as rats had chewed through the cables. “We used to seek out the repairman on cold wintry nights and bribe him with bottles of rum,” he recalls.

What followed in the next years was worse. A series of catastrophes—including 9/11 and SARS—hit air travel, depleting MakeMyTrip’s resources to dangerous levels. “We came within a month of our money [running out] and over a single weekend the team shrank from 40 to 12,” says Kalra.

eVentures had shut off a follow-up round after the dotcom debacle. That called for hard decisions. Kalra went without pay and moved operations to a tiny mezzanine rented at Rs 12 a square foot. “It was so small that if anyone moved, his knees knocked against the next person’s.”

The dotcom meltdown challenged the survival of every Indian ecommerce player. “Deep and I were in the same boat, and we regularly swapped stories,” recounts Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder of job portal Naukri.com. Kalra and his team constantly discussed closing down. Some cash dribbled in, and they plodded along.

By the mid-2000s things started to change. Indian Railways, the state-owned behemoth, launched online reservations and was making Indians comfortable with internet transactions. The country was in the midst of a low-cost airline boom. With private equity from SAIF Partners of India, which mainly focuses on India and China, MakeMyTrip finally commenced its India sales in 2005.

With other backers like Tiger Global of New York, Kalra was able to rebuild a healthy kitty. He used the cash to focus on the customer. “It was the first homegrown company to set up a call centre to serve Indian customers,” says Bikhchandani, who joined the board. And to his credit, the founder did not stray from the course. “Typical Indian promoters diversify even before they build something truly valuable. Kalra has been unwavering in his focus on travel,” said Neeraj Bhargava, the early investor whom Kalra later bought out.

MakeMyTrip and other online travel retailers soldiered on in the following years, but India’s internet payment system was still flaky. Many bookings would fail even after payments went through, and Kalra’s team worked feverishly to patch things up so no one was the wiser. “We never wanted the customer to think, ‘That didn’t work,’ and lose confidence in internet transactions,” says CCO Joshi.

Like purveyors of online travel in the West, MakeMyTrip realised that shrinking commissions made airline ticketing an unviable model in India. The firm needed to transit quickly into the more profitable market for hotels and vacation packages. But a business that would have taken a few years to build in the US turned out to be a lengthier struggle.

India hardly has any hotel chains. Its largest, the Tata conglomerate-owned Taj Hotels, has exactly 100 locations in India. Barely 5 percent of India’s hotels are online even today. Owners were dismissive and mostly “laughed us out of their offices”, recalls Aditya Saraswat, an early employee who later headed the online hotel sales before quitting last year. Today MakeMyTrip has nearly 100 market managers to enlist standalone hotels.

There also were buyer-beware factors. “For a long time we had assumed that consumer behaviour on hotel bookings was the same as consumer behaviour on airline tickets,” says Joshi. That was a bungle.

Airline travel is a standard experience, but customers booking slick-looking hotels online and arriving to find a dirty pool or a broken air-conditioner were sore. Sometimes in peak season small hotel owners refused to honour bookings when they could charge walk-ins more. MakeMyTrip’s brand took a bashing as customers angrily renamed it “RuinMyTrip”.

Kalra admits he also did not invest adequately in the back end. MakeMyTrip outsourced all tech requirements until a few years ago, when Bikhchandani joined the board and asked that the gap be plugged.

Kalra is trying to make amends by acquiring hotel aggregators and travel tech outfits, both in India and Southeast Asia. That is costing millions, but there is a payoff at the customer end. The traveller mind-set is so changed that last summer MakeMyTrip pioneered group charters and profitably flew planeloads of families to Bhutan and the Maldives. It has been ahead of domestic rivals like Cleartrip, which has just started offering air-hotel combos.

India itself has remained a tourism disaster. Travel infrastructure has not kept up with 7 percent average annual GDP growth rates of the last decade. “Young urban Indians who crave to get away on weekends cannot jump in their car and take off,” says Kalra. The roads are bad, rail connections inadequate and flying is too expensive after the collapse of carriers such as Kingfisher. India does not have budget hotel chains. “Just two cities in Thailand—Pattaya and Bangkok—have more hotel rooms than the entirety of India combined,” he says.

But MakeMyTrip adjusts to its circumstances. In 2008 it set up three storefronts—“touch-and-feel” shops, as Kalra called them. “In smaller places people trust brick-and-mortar retail.” His hybrid model consists of 59 stores today, some franchised at faraway locations. “Customers come to the store the first time, call us the second time and are ready to go online the third time.” The offline stores snare other types of customers, too—those who want credit, or small business owners such as a hardware store or a catering unit, which earn in cash and will spend only in cash.

Telecom infrastructure is unreliable, and the sector has been laid low by a series of corruption scandals and regulatory confusion. “One in three online transactions fails even today—we are helpless,” says Kalra. Less than 2 percent of Indians have credit cards, compared with 8 percent in China, as per a World Bank estimate. India’s internet base comprises only 122 million users, less than 10 percent penetration.

Precisely because of such challenges, sceptics describe India’s online retail model as burdened by high customer-acquisition costs. VC interest in the sector goes from euphoria—consultancy Technopak sees a $200 billion industry by 2020—to despair quickly, said Bhargava, the early investor. “You need 10 to 15 years of persistence to build big, profitable ecommerce businesses, but the booms and busts in capital availability kill many good companies,” he says. In that aspect Kalra has been lucky. Since MakeMyTrip’s Nasdaq debut three years ago India has not seen a single online retail IPO exit.

Yet entrepreneurs like Kalra keep their eyes on the sweeping change. Over the last decade India’s GDP has risen from $400 billion to $1.8 trillion. A whole generation, especially in smaller cities, is leapfrogging computers to access the internet on their mobiles. Smartphones, the key interface for mobile commerce, are expected to grow to 450 million by 2020.

“In the past decade this has been a better place to start a business than anywhere else in the world,” Kalra avers. “We are poised at the brink of something exciting.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)