IPL's power play: A hit for cricket lovers, money-spinner for its stakeholders

Over 10 seasons, the cricket league has seen its cumulative reach go up at a staggering pace and earned big bucks for advertisers and broadcasters alike

IPL introduced the concept of a glamorous sporting league in India, offering a new form of entertainment for Indian families

Image: Courtesy BCCI

By any measure, Rs 8,200 crore is a huge number. Consider that Rupert Murdoch-owned Star India paid less than half that amount, about Rs 3,851 crore, for the rights to broadcast Indian cricket between 2012 and 2018. So, when Sony Pictures Networks India (SPN) floated the number to bid for the ten-year broadcasting rights of the Indian Premier League (IPL), there were, understandably, a few jitters. There wasn’t clarity on whether IPL would be a Kerry Packer moment, revolutionising the game like the Australian media tycoon did in 1977 with his World Series Cricket played in “coloured pyjamas”, or remain “just another domestic league”.

The very first game played in front of a packed Chinnaswamy Stadium in Bengaluru in 2008 between Kolkata Knight Riders—owned by Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan—and Royal Challengers Bangalore—owned by liquor-baron-turned-wilful-defaulter Vijay Mallya—settled all doubts. Batting for KKR, Kiwi opener Brendon McCullum smashed an unbeaten 158 of 73 balls, peppering his innings with 10 fours and 13 sixes. As an exuberant Khan cheered from the stands, Bollywood numbers blared between shots, and crowd frenzy reached fever pitch as KKR beat the home team by 140 runs, Sony knew it had backed the right horse: Cricket plus entertainment would be a heady cocktail and IPL was here to stay.

Star India, which has been beaming IPL matches live through its online video streaming platform Hotstar since 2015, has seen its viewership surge to 100 million for the ninth season in 2016, up from 41 million. Ajit Mohan, CEO of Hotstar, says the online platform has seen “explosive growth” in IPL viewership not only in terms of the number of users, but also the depth of engagement: The average time spent by a user watching a match on Hotstar is 40-45 minutes, up from 30-35 minutes in 2016. “When we acquired the digital rights for IPL, we were betting on a young India, with access to smartphones and cheap data, coming on to our platform to view curated long-form content like live sports. The bet has paid off,” says Mohan. Hotstar, which was reported to earn Rs 65 crore from IPL in 2016, is estimated to cross earnings of Rs 200 crore in 2017.

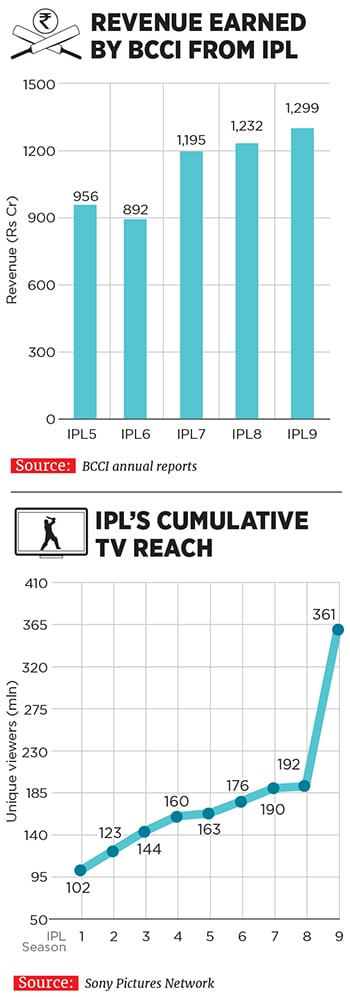

Not just the broadcasters, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), the governing body that owns and administers the league, is also minting money from it (see chart Revenue Earned by BCCI from IPL). According to BCCI’s latest annual report, it earned close to Rs 1,300 crore in IPL revenues in 2015-16, up from Rs 956 crore in 2011-12.

Image: Joshua Navalkar

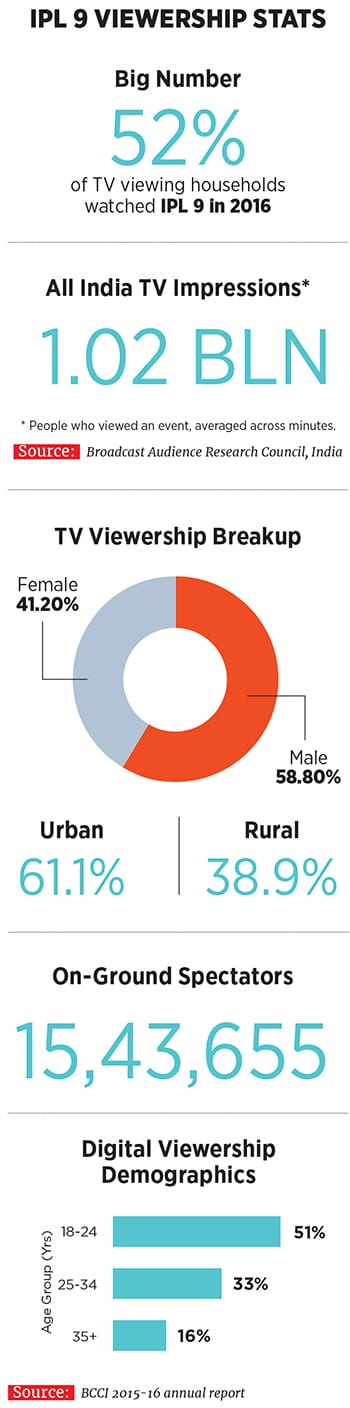

So what makes the IPL tick even in its tenth season? Smartly packaged content for the entire family, a short duration of four hours for each match and a high celebrity quotient. Launched soon after India won the inaugural T20 World Cup in 2007, the tournament was touted as a wholesome family entertainer rather than just cricket, often considered an overwhelmingly male domain. While much has been written on how some women anchors with debatable knowledge of the game were chosen to grab eyeballs, it can’t be denied that they democratised the viewership by bringing it out of the confines of elitism and punditry. According to a 2017 report by media planning agency GroupM’s sports arm, ESP Properties, 41 percent of IPL’s viewership (including in rural areas) comprises women. (See chart TV Viewership Breakup)

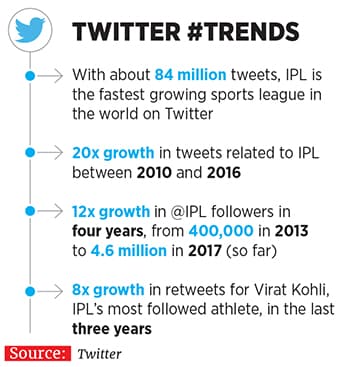

Keshav Bansal, director of Intex Technologies, which owns the Gujarat Lions team, says the IPL owes much of its success to edge-of-the-seat content. “People love to watch celebrities biting their nails as the teams they own battle it out in keenly-fought contests,” he says. “If led the right way, the IPL might well assume the proportions of the English Premier League (EPL).” That it can give its international peers a run for their money is evident from IPL’s growing popularity in social media: Between 2014 and 2016, IPL’s Twitter followers have surged 300 percent, compared to 239 percent for Uefa Champions league and 125 percent for NFL, the professional football league in America.

Keshav Bansal, director of Intex Technologies, which owns the Gujarat Lions team, says the IPL owes much of its success to edge-of-the-seat content. “People love to watch celebrities biting their nails as the teams they own battle it out in keenly-fought contests,” he says. “If led the right way, the IPL might well assume the proportions of the English Premier League (EPL).” That it can give its international peers a run for their money is evident from IPL’s growing popularity in social media: Between 2014 and 2016, IPL’s Twitter followers have surged 300 percent, compared to 239 percent for Uefa Champions league and 125 percent for NFL, the professional football league in America.Like the EPL, IPL’s ability to connect with fans through community-based franchises has augured well for itself. Perhaps no other team exemplifies that better than KKR, a rare IPL team that has consistently posted profits and, at 300 percent, grown its Twitter followers faster than English football outfit Manchester United (204 percent). In 2015-16, KKR reported a turnover of Rs 169 crore and a net profit of Rs 14.15 crore. Venky Mysore, CEO of KKR, says a large part of KKR’s success is due to the emotional connect with fans. “This will grow over time and transcend from one generation to another,” he says.

Basabdatta Chowdhuri, chief operating officer of Starcom Mediavest—the Publicis Groupe’s media buying agency in India—says the IPL brought the concept of a glamorous sporting league to India, offering an alternative to families for whom entertainment meant eating out or catching a film. “Media planners like us were certain the IPL would succeed. In India, cricket is a religion, Bollywood is a passion, and IPL offers both,” she says.

Such brand loyalty has generated significant economic returns for IPL’s stakeholders. For Chinese smartphone brand Vivo, for instance, the title sponsor of IPL since 2015, the tournament was a sureshot way of building brand recall. “Our journey in India started in 2014, and being a competitive market we were faced with brand recall challenges,” says Vivek Zhang, chief marketing officer of Vivo India. “Associating the brand with IPL put us in the spotlight immediately. As a brand, we have advertised our products through other channels as well—both digital and traditional. What we have realised is the magic still lies in IPL.”

Industry estimates indicate Vivo paid around Rs 180 crore to secure the title sponsorship for two years (2016 and 2017). According to the International Data Corporation, Vivo was the fifth largest smartphone brand in India with a 7.6 percent share of the market in the October-December 2016 quarter, growing 51 percent over the preceding quarter.

The other significant advertiser that has been associated with IPL for each of its ten seasons is Vodafone India. Around 25-30 percent of Vodafone India’s annual marketing budget is spent on IPL. “The time when IPL was being launched was also when Vodafone came into existence in India,” says Siddharth Banerjee, executive vice president, marketing at Vodafone India. “Over the initial years, IPL served the key role of building high visibility and strengthened the brand in India. As the brand has grown in India, the primary role of the IPL has transitioned to creating engagement opportunities with customers to drive business.”

The other significant advertiser that has been associated with IPL for each of its ten seasons is Vodafone India. Around 25-30 percent of Vodafone India’s annual marketing budget is spent on IPL. “The time when IPL was being launched was also when Vodafone came into existence in India,” says Siddharth Banerjee, executive vice president, marketing at Vodafone India. “Over the initial years, IPL served the key role of building high visibility and strengthened the brand in India. As the brand has grown in India, the primary role of the IPL has transitioned to creating engagement opportunities with customers to drive business.”The tournament has also significantly upped the buzz for business ventures that own franchises. For Intex, owning a franchise like the Gujarat Lions was a part of its marketing strategy to connect with youth, and not just make money. “We bought the team to promote brand Intex and acquiring a team based in Gujarat made sense since Gujarat is our strongest market,” says the 26-year-old Bansal. “In one year since purchasing the team, we have witnessed a 15-20 percent increase in sales across mobile phones and consumer durables in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh.”

Vivo and Intex’s association with the IPL has been facilitated by the controversies that have dogged the league over time. Vivo bagged the title sponsorship for two years after former sponsor Pepsi pulled out (serving three years of its five-year contract). While Pepsi didn’t comment, a senior executive of a media planning firm says Pepsi’s decision was indeed influenced by the controversies. Gujarat Lions was inducted in the IPL line-up after two of the existing teams—Rajasthan Royals and Chennai Super Kings—were suspended in 2013.

Vivo and Intex’s association with the IPL has been facilitated by the controversies that have dogged the league over time. Vivo bagged the title sponsorship for two years after former sponsor Pepsi pulled out (serving three years of its five-year contract). While Pepsi didn’t comment, a senior executive of a media planning firm says Pepsi’s decision was indeed influenced by the controversies. Gujarat Lions was inducted in the IPL line-up after two of the existing teams—Rajasthan Royals and Chennai Super Kings—were suspended in 2013. Sony’s Singh admits that the controversies did raise concerns about the potential impact on viewership. “We knew that anything which becomes very successful very soon will attract some amount of controversy. We addressed that concern with our very aggressive marketing campaigns, which focussed on the joy IPL brings to people,” he says.

Mysore says that, in an ideal world, such controversies shouldn’t occur, but such is the pull of the league that “from the time the first ball is bowled, the focus is entirely on the cricket”.

In 2018, IPL’s TV and digital broadcasting rights will come up for bidding again. The tenure of two new teams—Gujarat Lions and Rising Pune Supergiant—also expires at the end of the current season. Will the broadcasters and the team owners continue their association? Bansal has no doubts he would, should BCCI allow it.

So would Sony and Star, looking to expand their footprint in the digital and TV space, respectively. There is unanimity that the bidding war is going to be intense. According to a KPMG-CII report, the ten-year broadcast rights for IPL may be sold for something between Rs 16,000-20,000 crore, double of what Sony paid 10 years ago.

Sony may or may not sell an arm and a leg to retain IPL rights (“We will make an aggressive bid, but will stop at a certain point. At the end of the day, it is business,” says Singh), but should they jump in with an astronomical bid, there would no longer be any butterflies.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)