Deven Mehta: Smart Money with Smartcards

Deven Mehta got into the smartcard businessby accident and the orders are flooding in

Deven Mehta’s startup wasn’t even his idea. Many promoters come to pitch their ideas to the MD of SJ Group, an investment and real estate conglomerate. One Saturday, at his plush penthouse office in south Mumbai, he heard a proposal to manufacture smartcards—the kind used in SIM cards, driving licences and soon in ration cards—and put in 70 percent of the Rs 50 crore investment needed. The idea: As India develops, demand for smartcards will inevitably rise. The promoter said he was good for the other Rs 15 crore. It turned out, he had only Rs 36 lakh, and Mehta ended up taking on the whole business himself. For the first time, the 44-year-old went from being financier to the factory floor.

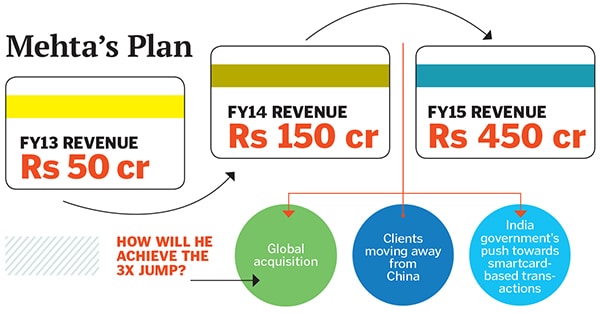

This was 2010. Last year, Smart Card IT Solutions (SCIT) had Rs 50 crore revenue and Rs 5 crore profits. Today, with the government mandating that SIM cards be made in India for security purposes, SCIT produces 14 million a month for customers like Gemalto, which sells them to telcos like Airtel and Vodafone. With growing financial inclusion, SCIT provides over 1 million personalised rural banking cards a month to customers like Genpact and HCL. Lastly, and perhaps most significantly, as all Indian government initiatives move towards smartcards (Aadhaar, ration cards, etc), SCIT is set to benefit. It makes 3.5 million Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana cards a month (80 percent of the market) that help people living below poverty line get access to medical insurance. In the year ending March 2014, Mehta says SCIT had a turnover of Rs 150 crore with profits of Rs 25 crore.

SCIT has been fortunate that demand has soared in all three of its verticals (SIM cards, government initiatives and financial inclusion), says Aditya Sanghi, group president and senior managing director, investment banking, YES Bank, who is helping syndicate SCIT’s ongoing overseas acquisition. Although domestic demand is high, experience has taught Mehta not to depend heavily on government demand. Since he supplies to global smartcard players, the way to move up the value chain was to enter emerging markets.

Mehta says SCIT will grow to Rs 450 crore in FY2015; this three-fold growth is almost too good to believe, and convincing private equity investors wasn’t easy. Now, however, he has interest from numerous PE players. SCIT produces over 1 million cards a day from its Pune facility, up from 120,000 a day in 2010, making Mehta one of the largest Indian producers. “The orders in my hand enable me to demonstrate that my Rs 150 crore will become Rs 450 crore next year!” he says. “I have a Rs 200 crore, three-year contract from one of the world’s biggest smartcard makers, and am in the process of finalising orders from the other biggies.”

Mehta is a practical person who likes to do things himself—even small things like memorising phone numbers rather than relying on the phone’s directory. When he wants to explain market dynamics, he gets out a pencil and paper. This approach has helped him change lanes from being a financier to taking on the nitty-gritty of highly technical production, says Dinesh Kanabar, deputy CEO, KPMG India, and an advisor to Mehta for 12 years. “Deven has been successful because he started with low-end products [like SIM cards] and has worked his way up the value chain to fulfilment centres [where cards are packaged and dispatched],” he says.

Production at global quality standards hasn’t come cheap or easy. Mehta sources printing machines, the backbone of the unit, from Germany. The Europay, MasterCard and Visa certification for banking cards, for instance, requires installation of 60 cameras in the factory, which alone costs Rs 5 crore! However, with China’s labour costs twice India’s, global smartcard leaders like Gemalto, Morpho and Oberthur have seen India’s advantage, says Kanabar.

Being born into a successful business family gave Mehta the comfort and acumen to take risks and try new things. Mehta’s father and founder of the SJ Group, Jitendra Mehta, began trading import licences (enabling large corporations to import/export goods) in Mumbai in 1960. At 16, Deven joined his father but found export incentives boring. With Rs 50 lakh from his father, he began exporting garments. As the family business grew, he got into strategic investing, with stakes in Gokaldas Exports and Vakrangee Software, among others. The SJ Group also has interests in real estate like Ambit House, in Mumbai’s Lower Parel business district.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)