Education technology and Indian schools

The coming age and future of technology in education

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

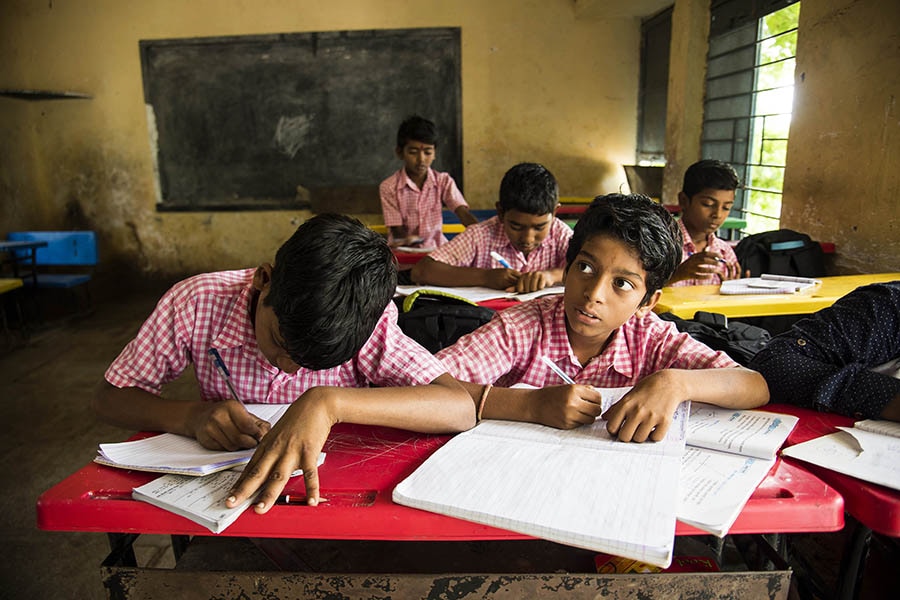

An important challenge for the Indian economy over the next few decades is to exploit the “demographic dividend” of having a large share of the population of working age. This dividend will only be earned with a well-educated workforce which in turn requires a strong school system.

In recent decades, India has increased school enrolment but struggled to deliver actual learning. An annual survey conducted by the NGO Pratham spotlights large learning deficits in basic reading and arithmetic. Only half of Class V students can read texts meant for Class II. More than half the students in Class VIII struggle to do simple division. Behind these abysmal outcomes are major structural problems including ineffective and sometimes absent school teachers, particularly in rural India.

Education technology (Edtech), mainly information and communication technology, can address these problems by delivering better lessons, training teachers and motivating students. In recent decades, the cost of computing has plummeted to the point where edtech is feasible even in relatively poor countries. Tablets cost as little as Rs. 2000 and India has the cheapest mobile data plans in the world.

At its most basic, edtech can help to deliver high-quality lessons in a variety of formats: text, video, games and interactive tutorials. On any given day, there are thousands of teachers who are teaching the same topic. Some do it well and others poorly. A well-made video can use the very best teachers and support them with graphics and animations. Once this video has been prepared, it can be watched potentially by millions of students over many years. The video can be supplemented with interactive quizzes which provided instant feedback to the student.

A deeper benefit of edtech is the ability to tailor lessons as per the progress of the student. For example Mindspark, a computer-assisted learning software developed by an Indian company, delivers lessons through videos, games and questions on computers and tablets. The software analyses each student’s learning level, pitches content suitable for this level and adjusts the difficulty according to the student’s progress. A study by MIT’s J-PAL evaluated a version of Mindspark targeted at 619 students in government schools in Delhi and found significant gains in Maths and Hindi. The initiative was also cost-effective with a monthly cost of around Rs. 1000 per student and an estimated cost under Rs.150 if the program was scaled up.

Another application of edutech, backed by research, is simple behavioural interventions delivered through technology, often just SMS messages. While the benefits of these interventions tend to be moderate, their cost is extremely low making them ideal for a low-budget school system. For example, automated text messages to parents about their child’s performance were found to increase both attendance and exam performance.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from Welingkar Institute of Management Development and Research (WeSchool)]