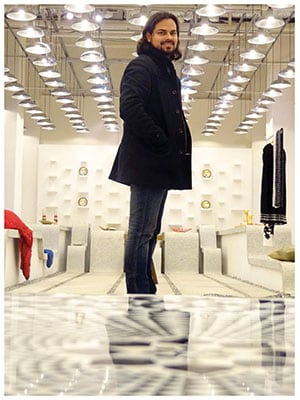

Rahul Mishra, the craftsman

Rahul Mishra's textiles tell a tale of Indian handloom through international design sensibilities

Rahul Mishra studied apparel design at the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad because he was not good enough to get admission for any of the other courses. But that, it turned out, was the best thing that could have happened to him. For last year, Mishra achieved the seemingly impossible: He turned the concept of wool on its centuries-old head, and transformed it into a summer fabric. For this, last year, he achieved one more thing that no one else before him had: He became the first Indian to win the International Woolmark prize.

For Mishra—born and brought up in Malhausi near Kanpur—this was the first part of an ambition that transcends national borders as well as stereotypes. “I wanted to do something big on the international scene within the first 10 years of becoming a professional designer. But I achieved this in the first seven,” he says.

Mishra has come a long way from his days in Malhausi, in Uttar Pradesh, where he—like most young boys his age—found himself studying for a Bachelor’s degree in physics at the Kanpur University. “Even 10 years ago, I would not be able to identify cotton from silk,” he laughs. “But I was always very good at drawing. In school I would always do very well in biology, because my diagrams were really good. I would even draw for my friends. It was only after going to NID I realised that I was not good at all!”

But it was NID that gave him wings, recalls the 35-year-old, sharing anecdotes about how he would attend lectures and workshops regardless of whether he was formally enrolled in them or not, how this freedom gave him a perspective that was far more inclusive than what his formal course could provide, and how it gave him the opportunity to study Kerala’s cotton textiles—“It is the purest form of cotton; it is next to God”—which was his first tryst with traditional, handloom textiles in India. “I had taken a train to Kerala, and was carrying the most fancy camera that NID had. Throughout the journey from Goa onwards, which was along the Konkan coast, I sat at the door of the train compartment,” says Mishra, the wonder of the long-ago years still spilling forth in his voice. “When I reached there, I felt like someone who is seeing Switzerland for the first time…”

This sense of wonder extended to the textiles that he came across. “I could not understand why the mundu which they wove was so long. And then I learnt that the men wear it in two layers because of the transparent nature of the fabric, and because of the fact that double layers of cotton dry twice as fast as a single layer of cotton.” The way in which the first acts as a hydrophilic layer (it absorbs moisture) and the second as a hydrophobic layer (it repels moisture) opened his eyes to the ways in which Indian handloom works, and the possibilities of using double layers of cotton. And this is where his background in science stood him in good stead: “We started using logic behind everything. Science became a tool to decode design.”

Adopting alien weaves and practices is not always the best way in which to use and market textiles. “Whenever a craft is desperate, it takes techniques from other crafts. Like taking jacquard or dobby weaves from Tamil Nadu, hoping that this will make the Kerala sarees sell,” he says. But this ruins the beauty and advantages of the original textile. After his work with Kerala handloom, he started looking at other crafts: Ikat of Odisha and Pochampally, bandhni of Gujarat, chanderi, maheshwari and khadi from West Bengal.

“Textile is actually a footprint of how humanity has lived in the region for the past one thousand years,” he says. “You can understand so many things about the people just by studying their textile.”

The collection of reversible garments that emerged from Mishra’s experience and learning in Kerala was humble; it used fabric that costs Rs 30 a metre. But it helped him understand the nature of handloom, and the disconnect that exists between the garment industry and the craft industry. The collection also made him realise how a clothing project can be a problem-solving exercise. “We have dreams of creating a big brand and things like that. But the weavers just want to earn enough money for food and send their children to school.”

Mishra strongly believes in the power of fashion to solve problems and bring about social and economic change. “The son of a weaver should have a choice of whether he wants to take up weaving as a profession or not. He should not be forced out of his family profession simply because there is no money in it,” he says. This philosophy has translated into strong partnerships with the artisans he works with. “I have no exclusivity contract with them; they can work for anyone,” he says. “If, in a bad year, I am unable to give them enough work, then they should not suffer for it. The artisans I work with have been able to build homes, own vehicle, have smartphones on which they send me designs through Whatsapp!”

Since Mishra has always worked with natural fibres, he has also worked with Merino wool. “Merino wool is inherently organic. I had discovered it three or four years ago, but had not realised its significance. I would use wool for the fall it would give a garment, or the way it would absorb light and made something less shiny.”

At the Woolmark event in Milan last year, Mishra was up against New York-based Joseph Altuzarra, Hong Kong-based label Ffixxed, Australian designer Christopher Esber, and London-based label Sibling. Mishra, who walked away with the prize money of $100,000, presented a collection that highlights the infinite possibilities of wool: Traditional Indian weaves, ornate embroidery, and silk jacquards. The graphically designed embroidery is inspired by Maurits Cornelis Escher and tells the story of how an eight-petal lotus evolves.

But Rahul Mishra is only one half of his brand. Mention his wife Divya, and he says, “She does 99 percent of all the work. She makes these bulky, industrial looking fabric into feminine clothes. She is the one who handles the cuts and styles of the collection, their sales and distribution… everything.” Divya, also a graduate from NID, studied apparel design before doing an internship in Milan. “She had got an offer from Roberto Cavalli, but she chose to work with me. That was a huge compliment!”

(This story appears in the Mar-Apr 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)