Movie musicals: Making a song and dance of It

Musicals are generic in Indian mainstream films while in Hollywood, they emerged as an antidote to the Great Depression

I was recently in brisbane, on the Asia Pacific Screen Awards Nominations Council that honours the best Asian films. On the long Brisbane-Mumbai flight home, one of the films that I watched was Mamma Mia!, the musical starring Meryl Streep, that is crammed end-to-end with ABBA songs. Call it a bonafide Western musical. It is close to Bollywood, in that the story is mainly a clothesline on which to clip a bunch of popular songs. The story is silliness in excelsis: Single mum Donna, who runs a hotel on a gorgeous Greek island, is prepping for her daughter Sophie’s wedding. Sophie invites the three sexy men (Pierce Brosnan, Colin Firth and Stellan Skarsgård) with whom her mum once had dalliances, determined to find out who her dad is. The climax is a spaghetti of ridiculous twists—and people gripe about Bollywood scripts.

OK, there is some feminism here, but the idea is primarily to run through the gamut of ABBA songs, from ‘Voulez-vous’ and ‘Dancing Queen’ to ‘Mamma Mia’. Scenes like Brosnan and Streep, standing back to back, crooning, ‘When you’re gone, how can I even try to go on?’ from ‘SOS’, are cringe-worthy, to say the least. Yet, Mamma Mia! is such a popular Broadway musical, and the movie version, since its release in 2008, still plays in cinemas worldwide, as a Christmas “singalong”. And once you see how inadequate Westerners generally are at directing lip-synced songs, you acknowledge the Indian gold standard in song picturisation, and appreciate the sheer craftsmanship our filmmakers have, shaping music, choreography, cinematography and editing, to pull off songs and dances with panache. Give the best filmmakers worldwide—Steven Spielberg, Luc Besson or Bong Joon-ho—a massive budget to picturise a song and dance, and they would not be able to match Mani Ratnam.

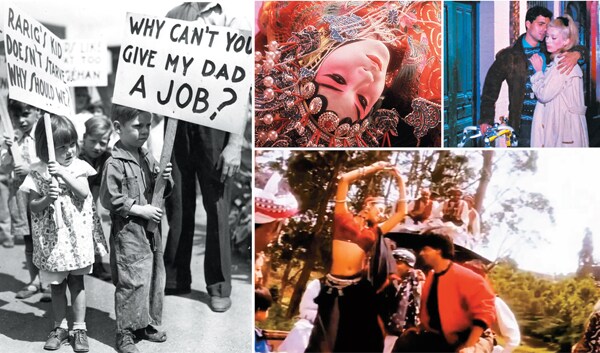

In Indian mainstream films, musicals are generic, and song and dance is part of the masala, along with romance, action, melodrama and a happy ending. As our early cinema drew from drama and folk theatre, which used song and dance as part of the narrative, these elements flowed organically into our films. In contrast, traditional wisdom has it that in Hollywood, musicals emerged as a genre in the 1930s, as an antidote to the Great Depression of 1929: For people in breadlines fighting unemployment, breezy musicals were an escape from reality (whereas escapism is permanently entrenched in the Indian DNA). So musicals with singing, dancing stars became popular, including Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (The Gay Divorcee, 1934), Shirley Temple (Curly Top, 1935) and Judy Garland (Wizard of Oz, 1939). Hollywood’s later, enduring musicals include The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Singin’ in the Rain, West Side Story, Grease and Cabaret. While some songs advance the story, they also have item numbers—random, happy songs that have little to do with the story, even if they are less pelvic than those in Bollywood.

When Europe makes musicals, they are very different from Bollywood, and even from opera, which originated in 16th century Italy. For instance, France has musicals as diverse as Jacques Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, 1964) and François Ozon’s 8 femmes (8 women, 2002), both big hits in France. Parapluies, shot in sumptuous colour, is a star-crossed romance between a woman in an umbrella shop (Catherine Deneuve) and a mechanic who is drafted into the Algerian war; when he returns, they’re married to different partners. There’s music throughout the film; all the dialogues are sung as “songs”. Years later, in the climax scene, they meet at the gas station—and still singing—while the attendant interrupts to ask her about the gas: “Shall I fill her up? Regular or super?” Interestingly, Deneuve is also in 8 femmes, a theatrical, musical murder mystery. At a family reunion, Deneuve’s husband is murdered: Is he killed by Deneuve, her sister or the maid? Let the chansons roll.

Danish director Lars von Trier’s musical, Dancer in the Dark, has a blind Czech immigrant in the US (played by Icelandic singer Björk) first exploited by a policeman, then unfairly given the death penalty. The film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and the songs were released as an album, ‘Selmasongs’, of which ‘I’ve Seen It All’ won an Oscar nomination for best song (Björk singing—with Deneuve again!). It is an ensemble song and dance shot atop a slow, moving train. I show this melancholic song in my film appreciation classes, right after ‘Chhaiyan Chhaiyan’, the item number from Ratnam’s Dil Se.., with ensemble dancers dancing on the roof of a running train—and you see the masterly wizardry in Indian song picturisation to create magic. No filmmaker can match this Indian talent.

India is not alone in Asian musicals: Chinese cinema has produced many films based on Chinese opera, from The Love Eterne by Li Han-hsiang (1963) to Chen Kaige’s spectacular Farewell My Concubine (1993); both doomed love stories involving cross-dressers, told through operatic songs and dances. Peter Chan even invited Farah Khan to choreograph his musical, Perhaps Love (2005). In Africa, Egyptian singing star Oum Kalthoum, idol of the Arab world, starred in several Egyptian musical films in the 1940s, including Fatma, Sallama and Dananir.

Much further south, there is the intoxicating U-Carmen eKhayelitsha by Mark Dornford-May (2005), Bizet’s opera set in the shanties of South Africa, which won the Golden Bear in Berlin. Spoken and sung in the local Xhosa language, its Carmen (Pauline Malefane) is a fat, black woman with purple lips, dressed in a grungy T-shirt and sneakers, singing and dancing to ‘Habanera’, balancing a soup mug on her head—yet is incredibly and powerfully sexy. For turning stereotypes on their head, for taking Western music, making it their own and socking us in the solar plexus—chapeau! This is a Carmen you will remember long after the rest.

The writer is South Asia Consultant to the Berlin Film Festival, award-winning critic, curator to festivals worldwide and journalist

(This story appears in the Nov-Dec 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)