Celebrating minimalism with Nasreen Mohamedi

Nasreen Mohamedi's retrospective in New York is part of a continuing celebration of an artist who said so much with so little

Imagine a lonely figure on a long-ago beach in Kihim mapping the pattern left behind by waves, lost in the symmetry of the susurrating lines, lonely, reticent, introspective. I next spot her fleeting presence among a heaving mass of grandees—curators, journalists, collectors, admirers—at the newly opened Met Breuer in New York, as they press closer to hear curator Roobina Karode speak about the extraordinary courage and conviction of an artist who died lamentably young at 53. What would that restrained figure have made of the hype and hoopla on Manhattan’s Madison Avenue? Was she aware of what destiny had in place as her legacy? Would she have rejoiced? Retreated?

I think of these things because the long arm of improbability has reached out from the past in the form of Karode’s curatorial narrative that is so emotionally charged that there are few dry eyes in the audience by the time she has finished. Those who had come to hear about an artist who has only just begun to capture global attention with the precision with which she unremittingly rendered straight lines and grids are moved by her haunting dedication to the pursuit of art at any cost. An artist who, in spite of a severely debilitating disease that she became aware of while fairly young, and which claimed her siblings, created works of such rousing luminosity that the Met Breuer—that extraordinary building which housed the Whitney Museum of American Art before it moved out and handed over the baton to the venerable Metropolitan Museum of Art—chose her to announce they were in business (along with a showing of incomplete works of several well-known European artists in ‘Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible’). It is a rare recognition for an Indian, particularly one who is so little known even in India. (The retrospective was at Met Breuer through June 5.)

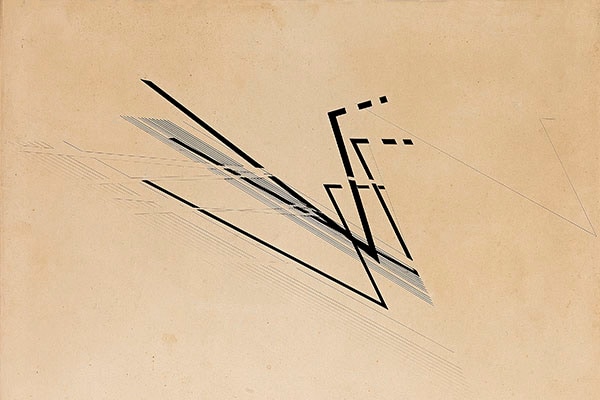

Untitled: Ink and graphite on paper (1970)

Born into a privileged lineage in Karachi, Pakistan, in 1937, Nasreen’s family moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1944 from where she was sent to study at Central Saint Martins in London (1954-57). When she returned to Bombay, chance led her to the cross-cultural Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute, where she frequently interacted with the great artists of the time: VS Gaitonde, with whom she shared an affinity for zen compositions and minimalism within the language of abstract art; MF Husain, whom she accompanied on frequent travels to Rajasthan during the shooting of his award-winning film, Through the Eyes of a Painter; and Tyeb Mehta, who went on to become the first artist to break the glass ceiling of million dollar prices in auctions. Eventually, she would shift to Baroda in 1972, where she would teach as well as practice till her death in 1990. (She died in the village of Kihim, near Bombay, where she had a family home.)

It was in Baroda that Karode met her. “I had access to Nasreen’s apartment (studio-cum-home) in Baroda on a regular basis,” she tells ForbesLife India. “Uncluttered and sparse, the studio had the ambience of a Sufi haven, the only furnishings a low drafting table and a low hanging lamp in the centre of the room. Nasreen mopped the floor of her studio/home several times in a day. The daily rituals of cleansing before sitting down to work were as mandatory for her as rituals of ablution before the offering of prayers.” It was something her elder sister Rukaya compared to ibadat, or the saying of one’s prayers.

Untitled: Ink and graphite on paper (1970)

Nasreen chose to move away and live on her own, haunted by the spectre of looming death. She had been diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, a neurodegenerative genetic disorder with debilitating loss of muscle coordination as it progresses. Her mother had died of it when she was just five, she had witnessed two brothers succumb to the disease, and her father and a nephew, too, added to the intimations of her own mortality. A brief interlude with love-turned-sour had put her off any romantic relationships thereafter. Calling on her own reservoir of inner strength, she emptied out her core to dwell on her work, noting in her diary that “solitude + strength/without compromise” indicated “freedom”.

Untitled: Ink, wash and graphite on paper (1975)

Her shaking hand had betrayed the direction her life would take, so she took to an architect’s tools to remedy it. Reading from her dairies while addressing a group of art students in New Delhi, Karode quoted the artist:

Labyrinths, lines among lines

A mesh

Difficult to destroy

Yet one must

Walk

Later, she would write:

Thought + geometry – geometry + thought

Layers + depths.

Vast space through complexity of thought

Thin threads into space…

A pure vision of non physical space.

Karode points to the artist’s immersive nature that confined her to a world within grids and lines contained in an elegant geometry, as though they might float, poised to fly. Critics have drawn comparisons with her love of photography—where, again, she concentrated on sparseness and shapes —as also in her seeking recourse in nature as well as architecture for inspiration. Art historian and critic Geeta Kapur reckons it to be “an understanding of geometry and light that the Arab civilisation has developed and honed into a magnificent aesthetic”—Nasreen’s family had spent many years in Bahrain and Kuwait —inferring that the “pencil of light” associated with photography, as well as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky later, informed her works. So did Gaitonde.

Nor must one forget the seeming parallel with another woman artist who, born in the same year as Nasreen, can hardly escape this comparison. Zarina Hashmi, who has lived in New York for four decades, has a vocabulary, at least superficially, similar to Nasreen’s in being abstract, minimal, while mapping geographies and forfeiting spaces recounted through nostalgia. That she, too, works within a language of lines and grids is mere coincidence; what is more apparent is that both are examples of the earliest Muslim women artists of 20th century India looking for solutions within a framework of lines that raise questions about space, existence, memory and light. Both rejected ethnic or religious characterisation and lazy stereotyping. Therefore, what Kapur says of Nasreen could as easily be true of Zarina, of the artist’s attempt “to sustain the continuum between finite and infinite and to not draw a perfect circle”, something Zarina reminded me on a recent visit to her New York studio, where she engaged in wistful homesickness that coincided with the opening of Nasreen’s retrospective. Karode refers to this as Nasreen’s “attributes of land, water, and sky to arrive at a mathematical abstraction one can simply admire, created through a tight weaving of lines over lines”.

Untitled: Untitled: Ink and graphite on paper (1970)

Not that Nasreen has been a stranger in the Big Apple, in no small measure thanks to the Talwar Gallery with its director Deepak Talwar, an avowed admirer of the artist. Back home, it was in New Delhi that Nasreen’s fortunes began to turn posthumously when collector Kiran Nadar agreed to take on the responsibility of representing the artist’s career at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. The moving force behind this was Karode, who had been “her student, friend, and neighbour” and had watched her “unfailing courage and luminous grace” from close quarters.

The retrospective was thereafter relocated from New Delhi to the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid and, eventually, as the opening show at the Met Breuer, winning critical acclaim and drawing parallels with Agnes Martin with whom Nasreen shared an interest in poetry and literature. If the Reina Sofia brought exposure, Met has been a coup for the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art where the retrospective has been hailed by co-curator and one of the most significant curatorial voices in the West, Sheena Wagstaff, as “a complex, multifaceted image of an alternative, nonformalistic modernity in which drawing becomes a means for investigating space”. Another critic, Deepak Ananth, writing in the catalogue Nasreen Mohamedi: Waiting Is a Part of Intense Living, refers to it as “a visual form of note taking”.

Untitled: Paper cutout (1980)

The Met retrospective marked another debut in New York, that of Nita Ambani taking an interest in the artist and the Reliance Foundation (the philanthropic arm of Reliance Industries, the owner of Network 18 which publishes ForbesLife India) funding the exhibition at the Met Breuer. It was the Foundation’s first public outing with art.

So what would have Nasreen made of this celebration of her work in New York? A few days later, at another lecture by Karode, I had my answer. “Nasreen,” she observed, “was probably aware of what lay in store but was not moved by it. She was committed to her work and to silence and she retreated into both as her health failed her. She never complained but you could see that she was shrinking into herself physically even while her art continued to soar in the form of her lines. I think she was aware of their destiny—and hers.”

(This story appears in the May-June 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)