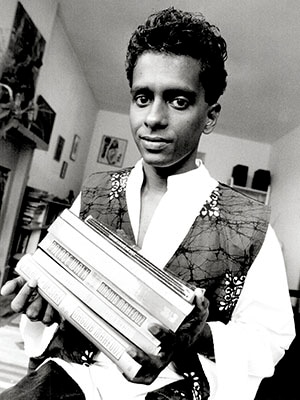

An exploration of greys with author Shyam Selvadurai

Sri Lanka-born Canadian novelist Shyam Selvadurai on the issues of sexual identity and the role of creative writing in healing the wounds of war

Partially set during the turbulent civil war years that escalated with the Colombo riots of 1983, Sri Lanka-born Canadian writer Shyam Selvadurai’s debut novel Funny Boy (1994) gained immediate acceptance as an important literary work that explored sexual identities, not only in the island nation but the whole of Southeast Asia. The novel’s enduring appeal has resulted in 11 editions in various countries and multiple reprints but Selvadurai, himself, has moved on from Funny Boy.

Selvadurai’s family migrated to Canada in 1983, when he was 19, amid the escalating Sinhala-Tamil tensions that resulted in several riots. He has returned to his roots to serve as the curator of the Galle Literary Festival in Sri Lanka that featured Indian writers Samanth Subramanian and Rohini Mohan whose books—This Divided Island: Stories From The Sri Lankan War and The Seasons of Trouble: Life Amid The Ruins Of Sri Lanka’s Civil War, respectively—garnered much attention. Selvadurai is also responsible for taking the festival to smaller Sri Lankan cities like Kandy and Jaffna to “expose local audiences to writers from other troubled spots like Palestine and South Africa”.

In an interview with ForbesLife India, he discusses, among other things, what his motherland Sri Lanka offered him as a writer, how Canada shaped his political views, acceptance of his sexuality and his rigorous writing schedule. Excerpts:

Q Funny Boy was a coming-of-age tale that dealt with homosexuality. I have heard many friends mention that they came to terms with their sexuality after reading the book. Did you anticipate it would have such a huge social impact?

I didn’t expect it to make the impact that it has. It really surprises me that the book keeps getting reprinted. Penguin India has even done a cheaper student imprint because I guess it must be read a lot in India. I grew up in a world in which I knew practically nothing about being gay and what was inside me. I wanted to break that silence with Funny Boy. I wanted some young queer person to read the book and feel that he or she is not alone in the world.

Q Have you ever wanted to revisit Funny Boy? To write a sequel, maybe?

No, definitely not. I am so sick of a book once I am done that the last thing I want to do is return to it.

Q What is the level of understanding of LGBTIQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and questioning] issues in Asian countries? Despite works like Funny Boy, sexual diversity is still taboo in much of Asia. Is there scope for change?

There is always scope for change. And sometimes change is incremental. But the level of understanding is woeful in Asia with punishing consequences for those who are LGBTIQ. Art has an important part to play in promoting understanding and tolerance, as it did in the West, around these issues.

Q How is the LGBTIQ writing in South Asia evolving? Any authors/works that have caught your attention?

I really loved Sandip Roy’s Don’t Let Him Know. I think it looks at the issue of being married and gay with great poignancy and complexity.

Q You view writing as playing a role in inter-community and inter-cultural healing and understanding. How has it helped in shaping your stories?

I think the healing aspect comes from seeing other people as also complicated human beings. So it’s very important for me that my writing is not polemic. That it explores the greys of human existence—the multiple shades of grey.

Q Tell us about the writing workshop, ‘Write to Reconcile’, that you have been conducting in Sri Lanka for emerging Tamil and Sinhalese writers since 2012. What has been the interest and outcome?

There has been a lot of interest in it. We are always flooded with applications. The outcome is an anthology that is read widely because there is also an online version. The first anthology was also translated into Sinhala and Tamil. I wanted to see if I could use my skills and knowledge of creative writing to do some good in post-war Sri Lanka. And ‘Write to Reconcile’ is what I came up with.

Q This year, the Galle Literary Festival you curated visited cities like Kandy and Jaffna. How effectively do you think literary festivals help shape social narratives on issues like war?

It [a literary festival] contributes towards this by offering a broader perspective that is not just Sri Lanka-based. It is good to expose local audiences to writers from other troubled spots like Palestine or South Africa. But, more importantly, there is a ventilation of ideas that go beyond war, which I feel is important to build a good civil society.

Q You directed plays like Mary Poppins, Peter Pan and Wizard of Oz in school. Why do you think it remained an unexplored passion after your writing career took off?

I studied theatre when I arrived in Canada, at York University, but at that time, there was little scope for South Asian theatre in Canada; there were no actors. So I made a conscious decision to switch to fiction and have not looked back since. After the wide canvas of the novel, I find going back to theatre very limiting as a writer.

Q Your family moved to Canada when you were quite young. How did displacement shape your creativity and your writing? Did it make you go back to your roots for inspiration?

By the time I left for Canada, I had already spent all my formative years in Sri Lanka. What displacement did was give me a chance to see Sri Lanka from a distance. Also, I wouldn’t have written or known how to write about being gay in a positive manner if I hadn’t lived in Canada. Politically, I was shaped by my time in Canada in the early 1990s—the identity politics movement.

Q After writing three novels firmly rooted in Sri Lanka [Funny Boy, Cinnamon Gardens and Swimming in the Monsoon Sea], you have touched upon the immigrant-novel genre and the theme of dislocation with The Hungry Ghosts. Do you consider it a transition from your previous works?

It’s more of something new than a transition. I don’t think that I am moving ‘forward’ by writing The Hungry Ghosts (2012). I don’t think I will now only write novels that deal with immigrants or the issues of the diaspora. I just write what interests me.

Q Could you weigh in on the current trends in the South Asian diasporic fiction? Do you think there is scope for more novels like Funny Boy?

I can’t comment on trends, as I don’t read so much South Asian diaspora fiction. There is always scope for more novels that explore the edges of society, that transgress in various ways. The role of the best fiction has always been to challenge societal expectations.

Q Do you have a writing schedule?

I write every morning from about 9-12, then I take a long break during which I have lunch and go for a swim or to the gym and then do a second session from 3-6 pm. I write as regularly as I can. When I am in Sri Lanka, and have no other commitments, I work seven days a week sometimes.

Q What are you working on now? Is there a novel in progress?

There is a novel in progress, but I never talk about evolving works. For me, it kills the work to do that.

(This story appears in the July-Aug 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)