James Packer: From Macau's Casinos to Hollywood

The legendary Kerry Packer lost a big chunk of his fortune at America's gambling tables. His son, James, has hit the jackpot by owning the casinos. Now he's rolling the dice on Hollywood

Slumped in white oversize chairs in an enormous suite at the Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles, Australian casino billionaire James Packer and Hollywood movie director Brett Ratner are exhausted. They look like two hungover frat boys after a hard night—but these guys haven’t been partying. They’re jet-lagged after visiting Russell Crowe’s film set in South Australia, watching Chinese tennis star Li Na win the women’s Australian Open in Melbourne and toe-touching in the Philippines to open Asia’s first Nobu restaurant at a new casino resort in Manila.

It sounds like a pleasure cruise from Packer’s earlier life as the polo-playing, jet-setting “Jamie”, son of the late media mogul Kerry Packer. In fact, it’s all business. Li Na is an “ambassador” for Packer’s flagship Crown Casino, which spreads across two city blocks on the banks of Melbourne’s Yarra River. The Manila resort is Packer’s first major casino foray outside of Australia and Macau. And Russell Crowe’s directorial debut, The Water Diviner, is financed by Packer and Ratner’s new Los Angeles-based film company, RatPac Entertainment, a Sinatra-inflected portmanteau of the two men’s surnames.

At 46, Packer is finally emerging from his father’s long shadow to come into his own as Australia’s second-richest person, with an estimated fortune of $6.5 billion. Sure, there are remnants of the flashy playboy lifestyle, including supermodel girlfriend Miranda Kerr, whose three-year marriage to English actor Orlando Bloom ended in October. (Packer split from his second wife, pop singer and model Erica Packer, née Baxter, in September, just weeks after the family moved into their Sydney mansion following a reported $35 million renovation.) By and large, however, Packer is increasingly regarded as a serious and successful businessman in his own right. He also has three children, aged 18 months to 5 years, who now live with Erica in Los Angeles, so he’s spending plenty of time on America’s West Coast.

“I had a marriage breakdown last year,” he says, after giving daughter Indigo, 5, a big snuggle before she trots of with her nanny to bed. “The last thing I think I am is perfect. I’m just trying to do the best job I can. I’m trying to be the best father I can to my kids. I’m trying to do the best job I can running my business.”

It’s been a bumpy ride. When Kerry Packer died in 2005 at age 68, his only son inherited a $5 billion fortune, mainly tied up in Australian magazines and television. At age 38, James Packer, who had been caretaking the family’s sprawling businesses for several years as his father’s health failed, was in full control. He moved quickly to reshape the Packer empire, selling most of his father’s beloved media properties to Hong Kong-based private equity firm CVC Asia Pacific for $4 billion in two deals across 2006 and 2007. The timing was perfect: He got out just as the internet began decimating traditional media’s revenue and profits.

Then he almost blew it. Packer plowed a big chunk of the cash from the CVC deal into casinos in Las Vegas, Pennsylvania and Canada, just before the global credit crunch. “I lost a bunch of money in America because of the financial crisis,” he says. Estimates of his losses go as high as $2.6 billion—roughly half of his fortune—and plenty were lining up to write his business obituary. Those losses included writedowns on investments in Fontainebleau Resorts, Station Casinos and Harrah’s (all in Las Vegas), as well as an ambitious but abandoned plan to build Crown Las Vegas.

Was he worried that the debacle would destroy three generations of Packer wealth creation? “I don’t want to answer that.” He will, however, share the biggest lesson he learned from that dark period. “Don’t be too leveraged—our balance sheet is now much more conservative than it was in 2008,” he says.

Las Vegas damaged more than Packer’s wallet. If the CVC deal showed he could be on occasion as shrewd as his legendary father, his North American shocker had him scrambling—again—to prove he could fill those huge shoes. Although Kerry Packer, too, had his share of business failures, he built a reputation as Australia’s most powerful and formidable businessman, owning the country’s leading television network and its biggest stable of magazines. He was most famous for selling his television network to fellow Australian entrepreneur Alan Bond for $700 million in 1987 and then buying it back for just $240 million three years later. “You only get one Bond in your lifetime, and I’ve had mine,” he gloated publicly.

Packer père was an old-style media baron with the domineering personality to match: A sometimes ruthless, foulmouthed bully who could also be charming, generous and funny. Every staff member received a generous Christmas basket, but those who displeased him also got the “Packer treatment”, an expletive-laden verbal dressing-down. The Australian public loved him for his sports-loving, one-of-the-boys persona and his laconic one-liners. When his heart stopped for several minutes in 1990, he told reporters that he’d been to the other side and “there’s f---ing nothing there”. He then donated around $2 million to have defibrillators fitted into New South Wales ambulances, which came to be known as “Packer Whackers”. By the time Kerry Packer died, he was Australia’s richest person, having built an estimated $100 million media business, which he inherited at age 37 from his father, Sir Frank, into a dominant broadcasting and publishing empire worth $5 billion.

James Packer made several great business calls before his father died but failed to shake the public’s perception of him as a bit of a dilettante and playboy. He championed the Packers’ acquisition of Melbourne’s Crown Casino in 1998, which became the foundation stone for their post-media fortune. He was ahead of most in betting on the rise of the internet, setting up Australia’s first major online news portal in 1998 and investing early in online car-sales and job-seeking sites. All three netted his family big profits. But these well-timed deals drew far less publicity than his biggest business flop (before Las Vegas), a disastrous foray into telecommunications. He and his good friend Lachlan Murdoch, son of Australia’s other media tycoon, Rupert Murdoch, invested heavily in One.Tel, which rapidly grew to become Australia’s fourth-largest telecom, before collapsing spectacularly in 2001 amid poor management, non-competitive pricing and legal issues. Although the Packer family’s $170 million haircut on One.Tel was a fraction of the Las Vegas loss, it probably hurt Packer more, since his famously abrasive father was still around to see the debacle—and lash him for it.

Shortly after the One.Tel misery, James Packer’s first marriage, to Australian swimsuit model Jodhi Meares, ended, and a depressed Packer fed the spotlight, flirting briefly with Scientology through his friendship with actor Tom Cruise. Seven years later, the Las Vegas near-death experience was another confidence-sapper. Luckily for Packer, though, he’d also invested in casinos in Macau—the special administrative area of China that now generates seven times the gambling revenue of Las Vegas—and this move proved his redemption. Crown put $600 million in Macau; it is currently worth $8 billion.

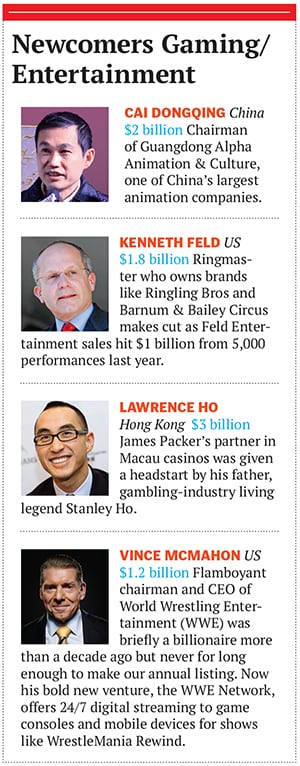

“I’ve now got more of my money in China than anywhere else, more probably than in Australia,” he says. His private company, Consolidated Press Holdings, owns a fraction over 50 percent of Crown Resorts, one of Australia’s top-performing stocks last year, leaping $3 billion in market capitalisation to $11 billion. What has the market excited is Crown’s 33.7 percent stake in Melco Crown Entertainment, a joint venture run by Lawrence Ho, the son of Macau casino tycoon Stanley Ho. It is Melco that has taken Packer into Macau, where the pair are opening a third casino in mid-2015, and also into the Philippines, where City of Dreams Manila opens later this year. Japan, too, is on the agenda if casinos are legalised before the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. Outside of the Melco joint venture, Crown owns casinos in Melbourne, Perth and London, and has approvals for huge casino resorts in Sydney and Colombo, Sri Lanka.

That Packer has hit the jackpot as the “house” is a twist on his heritage. Kerry Packer was a renowned whale, punting millions at blackjack, poker and baccarat tables around the world. He famously once said, “Toss you for it,” to a Texas millionaire at a Las Vegas casino who was boasting about his wealth.

“As a kid, I saw that dad lost a lot of money in casinos, and I didn’t understand that,” he says. “I thought this must be a great business. At the same time, I saw when I was with him—and I was with him a lot of the time—that this was a really cool business, and it was fun and glamorous. As I got older, I realised that he knew what he was doing. He was prepared to spend some of the money that he made to make himself feel better by giving himself an adrenaline rush. … Some of the happiest times I ever saw my dad was times when I was with him in the casinos and he had a good night.”

Does he wish his father were still around to see his current successes? “But then he would have also seen me in 2008,” Packer counters, presumably grateful not to have had to face paternal wrath over Las Vegas. He’s also mindful of his father’s urging to be realistic about business: “You’re never as good on your best day as everyone thinks, and you’re never as bad on your worst day as everyone thinks.”

Still, Packer concedes that with Macau he has hit the jackpot. Melco Crown, one of six companies with a Macau casino licence, has roughly 14 percent of the market.

“The business in Macau is going amazingly; I’ve been very lucky that it has been more successful than I would have thought possible,” he says, attributing much of that success to the work of Melco Crown co-chairman (with Packer) and chief executive Lawrence Ho.

The pair joined forces in 2004, bonding over a shared background of powerful billionaire fathers. “Our fathers [were] legendary businessmen,” Ho says. “In a certain way, they inspired us and also motivated us to do things even better and bigger.” More important, though, for Ho is Packer’s “100 percent trust and faith” in him, even through tough times. They faced a baptism of fire when their first project, the upmarket but poorly located Crown Macau (now renamed Altira), got off to a slow start in 2007. Then their second Macau venture, the $2.4 billion City of Dreams, opened in 2009. Unlike the Las Vegas gamble, however, Macau came good, with City of Dreams focusing on the mass market. Melco Crown also holds a 60 percent stake in a third Macau casino project, the $2 billion Studio City on the Cotai Strip, due to open in mid-2015 with a movies theme (and with obvious potential tie-ins to Packer and Brett Ratner’s RatPac Entertainment).

“Trust” is a word that Ratner also uses to describe his relationship with Packer. “I know he predominantly bets on the person,” says Ratner, who directed the Rush Hour film series and X-Men 3: The Last Stand. “His belief in Lawrence Ho and, of course, myself gives his businesses the confidence to excel.”

While Packer’s growing casino interests are his main focus—and the reason his fortune is up by nearly $2 billion in two years—it’s clear that RatPac, formed in December 2012, is not just a rich man’s dabble in a glamorous industry. “The casino business and the movie business are similar,” Ratner says. “What you’re selling is an experience. You’re selling adrenaline.” In September, RatPac closed a $450 million deal with Warner Bros to co-finance up to 75 films over four years. If things go well, Ratner says, the financing could top $1 billion. Their first film Gravity has been a huge hit.

Now RatPac is moving beyond the movie business into TV, book publishing and documentaries, and especially into China and India. The ultimate aim? A global brand focussed on Asia’s growing middle-class thirst for entertainment. Exactly like Packer’s Crown Casino empire.

“The thing that was at the centre of our thinking all along is the rise of China,” says Packer. “I think ten years from now a bunch of studios will say, ‘Why didn’t we do more in China?’ ” Outside of the Warner deal, RatPac closed a three-year deal in December to help pay production costs on movies made by Brad Pitt’s Plan B Entertainment and will finance films by Cameron Crowe, Warren Beatty, David Fincher and Roman Polanski. It is also producing a Horrible Bosses sequel and Hong Kong Phooey, starring Eddie Murphy. “The point is, we are ambitious enough, whether foolish or smart, to want to participate in the development of our own content,” Packer says.

RatPac’s broader media strategy includes buying one or more TV production companies, creating documentaries with Netflix and publishing Ben Mezrich’s (Bringing Down the House, The Accidental Billionaires) next book. In some ways, it’s a return to Packer’s media-company heritage but with a 21st-century spin. “I don’t think I ever got out of the media business,” he says.

For now, Packer looks to be on a winning streak. If RatPac proves to be another Macau, there’s little doubt he will perhaps surpass his father’s achievements. He also has high hopes for his other US play, a 9.35 percent stake in real estate portal Zillow, bought for $250 million. And clinching approval last November for a controversial $2 billion casino resort in hometown Sydney was a defining moment for the “new” Packer, giving him the chance to make his own mark on the city his father once dominated. But he’s used to placing big bets and sometimes getting stuck with a losing hand. “I’ve made a bunch of mistakes in my life. I’ve had my ups and downs,” he says. “Business is good right now, but now my personal life is a disaster.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)