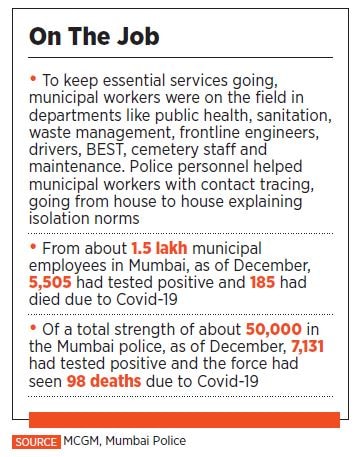

Unsung heroes: Cops and municipal workers at the frontline

Police men and women, along with municipal workers ensured humanitarian help and essential supplies were readily available during the Covid-19 lockdown

Nisha Chavan, police sub-inspector at the Kherwadi station, contracted Covid-19 while on duty

Nisha Chavan, police sub-inspector at the Kherwadi station, contracted Covid-19 while on dutyImage: Emmanuel Yogini for Forbes India

In late September, police sub-inspector Nisha Chavan was taking down the statement of a domestic violence victim. The woman was hurt and couldn’t wear a mask, and for Chavan, the priority was to get her to a hospital as soon as possible. The victim tested positive for the coronavirus and a few days later, on October 3, so did Chavan.

She isolated herself, got admitted to a hospital for a week, recuperated at her house in Vashi, and finally after 18 days, went home to her parents, in a village near Pune.

“I didn’t tell my mother because she would unnecessarily worry,” says the 27-year-old who has been on the frontline since March, first working long hours through the early months of the lockdown, helping send migrant workers home, and then once things opened up, policing and ensuring people stuck to curfew and lockdown guidelines.

“Those first two months, I used to get to work at 8 am and leave at 2 am in the night,” recollects Chavan, who got to work from her house in Vashi to Kherwadi police station in Bandra on her bike or in a bus. Migrant workers who wanted to leave the city had to fill forms, 10 names in a form, with the number of the person to be contacted when trains and transport became available. “We used to start making calls in the morning, tell that contact person to bring the nine other people along and organise their movement so that they could leave on the trains from Bandra Terminus to Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan,” says Chavan, who was part of a team of 12 young police personnel from Kherwadi police station, interacting with migrant workers in the area. Being on the frontline meant seeing the conditions of migrants up close, and the team at Kherwadi went beyond the call of duty by organising food through sponsors and later even pitching in with their own funds, she says.

The trains usually left in the afternoon and evening, and after that the information had to be collated and uploaded. “The migrants were desperate to get home and we covered the area from Bandra-Kurla Complex to Sahar,” says Chavan.

Once the migrant situation eased, she was back to police duty, naka bandis and getting people to stick to the lockdown guidelines of two or three people in a vehicle. While her entire team at some point or other got Covid, she was struck much later. “Being on the field, it was going to happen sooner or later… we also had documents coming in from hospitals that had to be processed and it wasn’t possible to constantly take precautions,” she says.

And then there were those not visible on the field but who worked through the lockdown to keep services that Mumbaikars take for granted running. Among them was Iftekhar Ahmed Shaikh, assistant engineer (distribution and control), who monitors water supply for the eastern wards from Mulund to Sion along with his team of four engineers and three other staff, ensuring the intricate balance of flow of water from reservoirs to citizens’ homes. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai has a water supply scheme for the year and a designated amount of water is supplied to various wards each day.

“Ours is a super emergency department, a control room. We have to have one junior engineer and one peon deputed for this all the time. The engineering staff work in shifts, and the person on duty cannot leave until the next person comes in, because he has to manage and control the distribution system. We take hourly readings for the levels and pressure, and accordingly manage water supply,” says Shaikh, who lives in Ghatkopar (West) and made his way to work during the lockdown on foot.

Iftekhar Ahmed Shaikh works with the team that monitors water supply in the eastern suburbs of Mumbai from Mulund to Sion

Iftekhar Ahmed Shaikh works with the team that monitors water supply in the eastern suburbs of Mumbai from Mulund to SionImage: Emmanuel Yogini for Forbes India

The rest of the team, however, came from distances as far as Ambernath, Asangaon, Panvel and Thane. They got to work on two-wheelers, flashing their identity cards to be let through, and stayed on for two to three days at a time, then taking a break for four days to rest at home as well as quarantine.

Shaikh adds that during the complete lockdown there was no food available so arrangements were made and the team even cooked on site, bringing groceries from home and surviving on dal and rice.

“My building too had restrictions and there were eyebrows raised at my leaving for work every day, but I told them that if I didn’t go to work, they wouldn’t get water,” says Shaikh.

While Shaikh and his team kept the essential service of water going without a blip in the face of fear and panic, Chavan too resolutely went about her work, including signing off on papers related to Covid-19 deaths. “I remember a young woman who came in with her cousin. Her entire family had contracted the virus, the father had died and the rest of them were in hospital, she needed our signature for the disposal of the body and she was doing all this on her own, and she couldn’t stop crying,” recollects Chavan. “It was heart-wrenching… I felt bahut bura haal chal raha hai, the virus is causing so much suffering.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)