Women's hockey: On a stronger turf

Women hockey players, who have overcome personal trials to come together as a competitive unit, are now eyeing a podium finish at the Olympics

Sunita Lakra and Lalremsiami, part of the Indian women’s hockey team

Sunita Lakra and Lalremsiami, part of the Indian women’s hockey teamImage: Selvaprkash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

It’s about 8 am and even as the rest of Bengaluru is yawning off its sleepiness, a group of girls at the Sports Authority of India ground at Mallathahalli is caught in a tussle. “Ball leke aa (fetch the ball)”, “stay low”, “good going”, they bark at each other till a whistle blares from the other end. Then, before the echo can ebb, someone else hollers, “Start cooling down.”

This is no ordinary catfight, though, but a glimpse of the high-intensity, ‘red session’ that 18 of India’s national women hockey players are undergoing ahead of a tournament in South Korea in May. Off the field, these shy, reticent girls can, at times, turn into an interviewer’s nightmare with an economy of words. But wait till you give them a hockey stick and watch them dribble, push, flick and thread a defence with clockwork precision.

Recent success has much to do with transforming the sporting backbenchers into a vocal bunch. In 2016, the team qualified for the Rio Olympics after a 36-year hiatus. They followed it up by winning a Gold medal in the Asia Cup the next year and a Silver in the Asian Games in 2018. This January, they beat the World No 7 Spain by a record 5-2 margin during a tour to the country and Ireland 3-0, and during their Malaysia tour in April, won four out of five matches. In the last four years, two of their top players—captain Rani Rampal and vice captain Savita Punia—were given Arjuna awards, in 2016 and 2018 respectively.

“In the last few years, we have graduated from defensive game to attacking game. We are playing much faster hockey than we used to a few years back and that has been possible due to a balanced team (comprising experienced and fresh talent), and a supportive staff,” says Rampal.

The man behind the team’s recent transformation is coach and former Dutch player Sjoerd Marijne who took over the women’s outfit in 2018 following a somewhat controversial move by Hockey India. Marijne, who had joined the women’s team in 2017, was moved to the men’s team for nine months before being sent back once both the men’s and women’s team returned from the Commonwealth Games empty-handed. But it hasn’t affected his dynamics with the players as the team has climbed up the International Hockey Federation (FIH) rankings from 13th to the current 9th ever since he took charge. Says Marijne, “Indian hockey players always had the necessary skills, now we are focusing on getting the smaller things right, consistently, so the team can compete with top teams.”

This brand of competitive, aggressive hockey isn’t merely a result of the administrative change, but of the way in which they train and lead their lives. The team’s scientific adviser, Wayne Lombard, who joined in 2017, explains how they made changes to the players’ diet to make them faster and fitter. Nothing major, he adds, but tweaks like removing bread, white rice and anything that contained fat. “We did not bring about drastic changes as we did not want to disrupt their lifestyle,” he says.

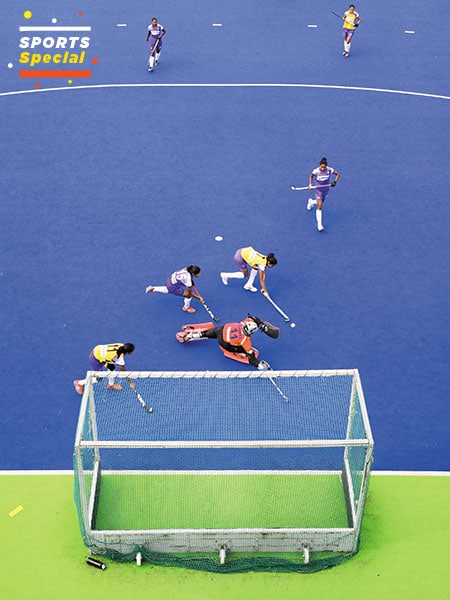

A training session in Bengaluru

A training session in BengaluruImage: Selvaprkash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Besides, players now have to undergo a Yo-Yo Endurance test, developed by Danish soccer physiologist Jens Bangsbo, once they are back from long breaks. One might recall that cricketers Yuvraj Singh and Suresh Raina had fallen out of favour with the national selectors reportedly after failing the test. Wary of similar outcomes, the self-driven hockey players now stick to their fitness schedules even during holidays.

There has also been a perceptible shift in the attitude of the sporting associations towards the players. Earlier, they were sent home if they were injured, but now SAI or Hockey India looks after their injury rehabilitation even during off season by bringing them to the camp, picking up the tabs for treatment and keeping them in rehab till complete recovery. Skipper Rani Rampal was one such case after she missed out the team’s Malaysia tour due to injury.

It helps that sponsorships have been pouring in for the game, which is at an inflection point. Last year, in a first of a kind association, the Odisha government came forward to sponsor both the men’s and women’s hockey teams for five years. The Indian teams now sport a jersey with a logo that encapsulates the state’s signature coastline, the Olive Ridley turtles, the Konark wheel, their dance form and hockey. It’s a far cry from the times core players like Deep Grace Ekka, Nikki Pradhan and Sunita Lakra had to play barefeet or those like Lalremsiami and Sushila Chanu needed borrowed equipment to get on the field. Now, each of them can boast of individual sponsored gear.

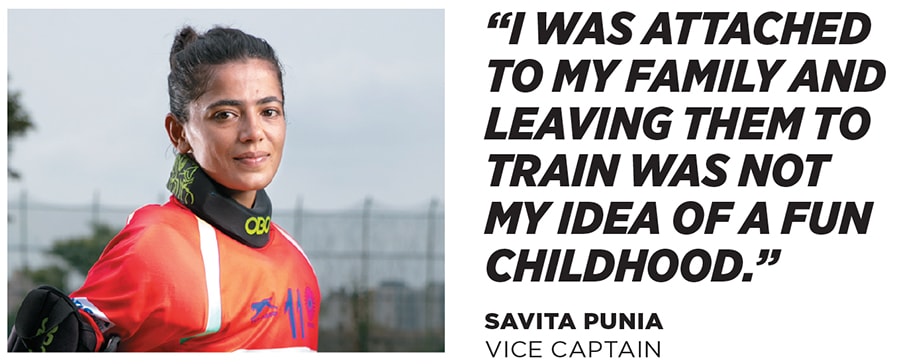

Hockey, or sports for that matter, wasn’t always the first choice for vice captain Punia. It was her grandfather Mahinder Singh, an advocate for equal opportunities for girls, who insisted she take up the sport. Spotted by her coach Sunder Singh Kharab, Savita began her journey in 2004, when she was 14. “I was very attached to my joint family and the thought of leaving them to train in a hostel was not my idea of a fun childhood. But things changed after I began playing competitive, professional hockey after being selected to the national team in 2007. Passion for the game and representing India at the world stage took ever,” says Punia.

Deep Grace Ekka, 25, who hails from Sundergarh in tribal Odisha, found her inspiration in her elder brother who was a hockey player himself. There were no dearth of role models around as the district has produced nearly 90 professional players, including the likes of Dilip Tirkey. Such was her passion for the game that she braved abject poverty in her early years practising barefeet. Ekka, defender and now a drag flicker (a skill useful in taking penalty shots), has given stellar performances in the matches where the team won Bronze in Asia Cup in 2013 and Silver in Asian Champions Trophy, 2013.

A deep fondness for the game is also what saw Jharkhand’s Nikki Pradhan, 25, through in her early years, when she was asked to vacate her hostel in Bariatu, Jharkhand, in 2008 without any explanation. But word about her proficiency had reached other coaches who gave her a smaller accommodation in another hostel. Their faith in Pradhan was vindicated when she made it to the junior team in 2011 and the senior team in 2015. Pradhan also made history by being the first woman from Jharkhand to play in the Olympics in 2016.

Now players like Pradhan and Ekka bring their steely grit on to the turf with their never-say-die attitude. “The team has the required skill sets, but their personal battles have already made them much stronger than many others,” says Marijne.

Senior players like Rampal have also made significant contributions in chiselling individual players into a well-knit team. Players now hang out or go for movies or shopping once practice is over. “Now every player can speak their mind if they have feedback or want something to change,” says Ekka .

“We used to be nervous around our seniors as they were strict. But now there is no hierarchy as such which makes things easier for everyone on ground,” says Sunita Lakra from Rajgangpur in Odisha. Lakra recently got married, but has bucked the trend by returning to the game thereafter.

Rampal also took under her wing 19-year-old Mizo forward Lalremsiami, who had been struggling due to language hurdles. Lalremsiami was not comfortable in English or Hindi, which made it difficult for her to communicate or receive feedback during matches; the team had to speak to her through gestures. But within a year, Lalremsiami, who shared her room with Rampal, picked up Hindi and English from her teammates and through self-learning books. “I took the help of self-help books like Learn English in 30 days and my teammates also helped me a lot. I will say I am still learning,” she says in almost-fluent English. Rampal also acts as the translator between the foreign coach and the players, most of who are not comfortable in the language.

Scientific adviser Lombard says there was a time when the team’s morale would be hit hard with a loss during a tournament, but now the players confidently move past a loss in a series and prioritise winning in the next match.

For this, they undergo specific mental training and psychology classes. Says Punia, “The coach and the entire staff associated are always positive about our chances of winning. Their confidence helps boost the team when things are not going in the right direction.”

Right now, in the build-up to the Olympics in 2020, the team will need all the poise and positivity. The FIH Women’s series finals in Japan in June will take them one step closer to the tournament. Their journey from being the underdogs to contenders is complete. But now it’s time for another.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)