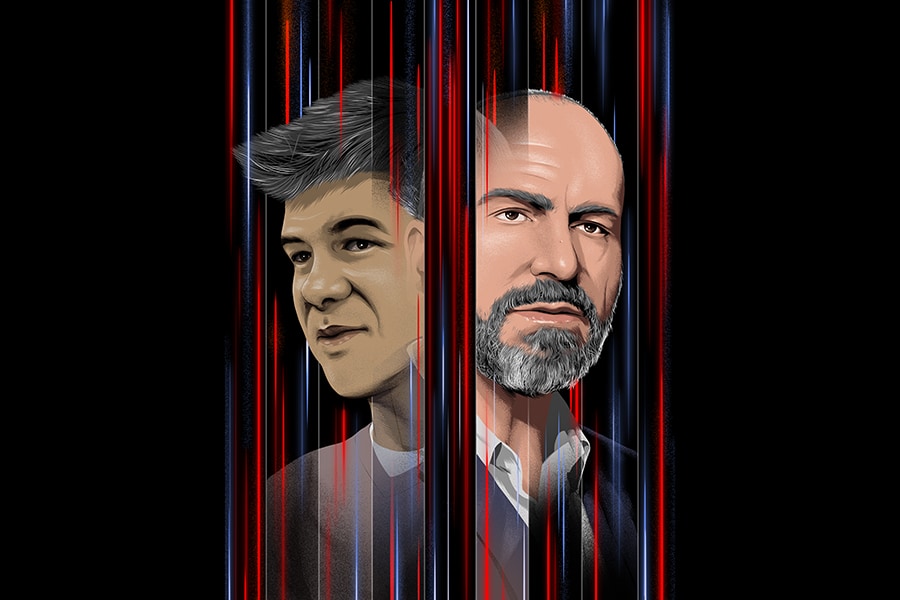

With Uber's IPO, Dara Khosrowshahi is taking Travis Kalanick's company public

The CEO wants to prove that the start-up has evolved past a raucous, and profligate, tech-bro culture. But Uber's past is simply not that far gone.

Dara Khosrowshahi had a problem. His name was Travis Kalanick.

That, of course, was nothing new. When Khosrowshahi took over as chief executive of Uber in 2017, he became the best-compensated janitor in Silicon Valley, with a mandate to clean up the mess left by the company’s exiled founder. But this time, in mid-April, Khosrowshahi faced a Travis headache that lay in the future.

Uber was just weeks away from its initial public offering. After years of scandal, infighting and user revolt, this was supposed to be a $91 billion moment of triumph, when employees would become wealthy and the public could buy a piece of an indisputably world-changing company. The problem for Khosrowshahi, according to two people briefed on the matter, was that Kalanick wanted to be there.

As a former CEO and current board member, Kalanick had asked to take part in the hallowed New York Stock Exchange tradition of ringing the opening bell on May 10, the day Uber shares are slated to begin trading. He also wanted to bring his father, Donald Kalanick. It would be close to the second anniversary of the accidental death of Travis Kalanick’s mother, and of the dramatic boardroom coup that ousted him as boss. His presence on the exchange’s iconic balcony could make both Kalanick and the corporation appear resilient.

Khosrowshahi wasn’t having it. The original plan was to fill the rafters with Uber’s earliest employees and longest tenured drivers. Moreover, some people at the top of the company felt that Kalanick was still a toxic liability and that Uber should keep him at maximum distance as it tried to convince constituents that employees truly abided by a new motto: “Do the right thing. Period.” Kalanick’s appearance would unavoidably rekindle public memories of just how much of a disaster his final year was.

Besides, Khosrowshahi had bigger things to worry about than IPO pageantry. Uber is losing billions of dollars annually, and he needs to convince investors that it is a promising, long-term company — even if it won’t be turning a profit anytime soon. He didn’t need the distraction at Uber’s financial coming-out party. On Thursday evening, after The New York Times approached Uber for comment on this article, Khosrowshahi decided that Kalanick wasn’t welcome on the balcony, according to an Uber executive briefed on the plans.

©2019 New York Times News Service

Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s chief executive, in San Francisco, Aug. 24, 2018.

Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s chief executive, in San Francisco, Aug. 24, 2018. Travis Kalanick then the chief executive of the ride-hailing service Uber, in New York, May 2, 2011.

Travis Kalanick then the chief executive of the ride-hailing service Uber, in New York, May 2, 2011.