UN Climate talks end in few commitments, 'lost opportunity'

The annual negotiations, held in Madrid this year, demonstrated the vast gaps between what scientists say the world needs and what the world's most powerful leaders are prepared to even discuss, let alone do

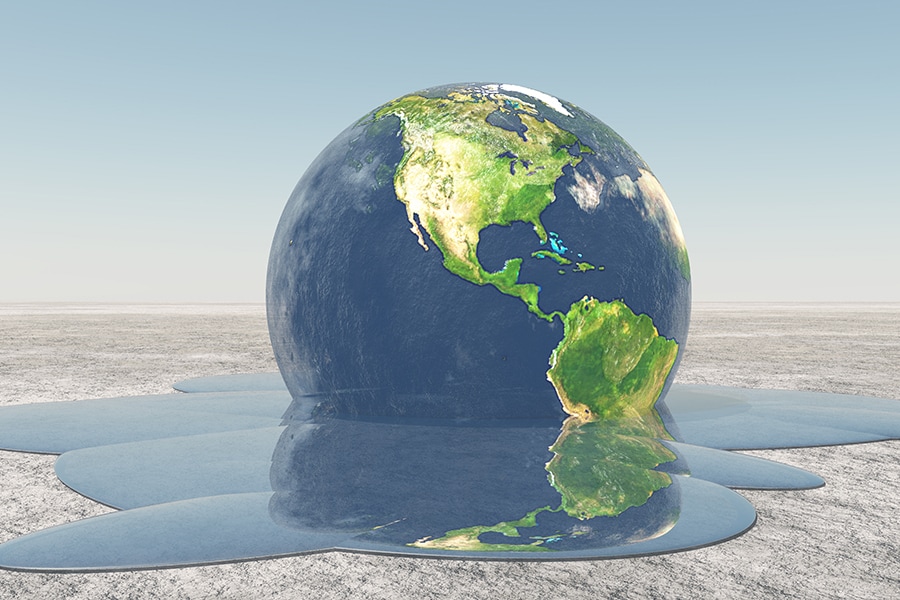

Image: Shutterstock

Image: ShutterstockIn what was widely denounced as one of the worst outcomes in a quarter century of climate negotiations, United Nations talks ended early Sunday morning with the United States and other big polluters blocking even a nonbinding measure encouraging countries to enhance their climate targets next year.

Because the U.S. is withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement, it was the last chance, at least for some time, for American delegates to sit at the negotiating table at the annual talks. They also used that chance to push back against a compensation mechanism, long-sought by developing nations, for the economic losses poor countries suffer from droughts, storms and slow-moving climate effects like sea level rise.

The annual negotiations, held in Madrid this year, demonstrated the vast gaps between what scientists say the world needs and what the world’s most powerful leaders are prepared to even discuss, let alone do.

“Most of the large emitters were missing in action or obstructive,” said Helen Mountford, a vice president at World Resources Institute. “This reflects how disconnected many national leaders are from the urgency of the science and the demands of their citizens.”

The outcome leaves many important decisions to be made at next year’s negotiations, which will begin in Glasgow, Scotland, immediately after the U.S. elections next November.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres offered an unusually blunt assessment of the 25th annual negotiations, formally known as the Conference of Parties. “I am disappointed with the results of #COP25,” he said on Twitter. “The international community lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation & finance to tackle the climate crisis.”

The negotiations, which had been scheduled to end Friday, extended into the early hours Sunday. It was the longest Conference of Parties ever, and it came against the backdrop of accelerating climate threats.

Although there was a general endorsement of finding a way to help poor countries cope with climate disasters, an agreement for funding failed on the question of whether major polluters could be held liable for climate damages in the future.

The delegates also deferred until next year an agreement on rules for international carbon trading. Australia and Brazil were among those who insisted on what were widely described as accounting loopholes.

A coalition of small island nations said in a statement that it was “appalled and dismayed” at what it called the scale of inaction and the failure to reach decisions on critical issues.

The talks had been meant to iron out the last unresolved details of the landmark Paris climate agreement. Under that pact, reached in 2015, countries set their own targets and timetables to rein in emissions of planet-warming gases.

There was a push from both rich and poor countries to commit, at least on paper, to ramp up climate-action targets next year. That is important because even if all countries meet the voluntary targets they have set so far, according to the scientific consensus, emissions are rising at a pace that makes storms and heat waves very likely to become more severe, and coastal cities to be at risk of drowning.

But there was no diplomatic consensus on even that. The final declaration was notable for what counts as exceptionally weak diplomatic language: It cited only an “urgent need” to reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement.

China and India joined the U.S. in pushing back against more emphatic language calling on countries to enhance their climate-action targets in 2020. The European Union joined many poor, vulnerable countries in calls to be more ambitious, although it remained unclear when the bloc, which is one of history’s biggest polluters, would update its own targets.

State Department officials did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The outcome was also notable in that it followed a surge in street demonstrations this year, often led by young people, highlighting the deep fissures between the demands of thousands of ordinary citizens and their governments.

One of the most contentious issues that was kicked down the road was a set of rules on carbon trading, which would allow countries and companies to trade on emissions reductions. Australia and Brazil were among those countries that insisted on accounting loopholes, including the ability to carry over credits earned under an old trading system. That was considered unacceptable by others.

Some environmental advocates saw a silver lining there. No deal on carbon trading was better than a bad deal, they said.

The U.S., the only country in the world retreating from the Paris accord, stuck to its long-standing position on compensating countries that are pummeled by extreme weather events and slow-moving climate effects like sea level rise.

A coalition of these countries has long sought a form of “loss and damage” reparations not currently available from other climate funds, which are designed to help reduce emissions and adapt to climate effects. The one bit of progress made on this issue was an agreement to set up a review that looks at how to best compensate countries hit by disasters.

The United States insisted on language to protect itself from liability claims, delegates said, blocking progress in the loss and damage talks. The U.S. has defended its position by saying it is the largest humanitarian donor in the world.

©2019 New York Times News Service