Markets in 2019: You couldn't lose money if you tried

This year, however, a simpler strategy would have worked: Buy almost anything

As the Fed flipped toward lowering interest rates, virtually every type of investment soared in 2019.

Stocks? Buy ’em. Bonds? Back up the truck. Gold? Why not? Hogs? Sure!

There’s usually a tension across financial markets: If risky bets like stocks or junk bonds are doing well, super-safe assets such as government securities might be terrible investments. Wall Street’s titans and armchair investors alike expend tremendous amounts of time and sweat trying to predict what will be up and what will be down, hoping to beat everyone else with a cleverly constructed portfolio.

This year, however, a simpler strategy would have worked: Buy almost anything.

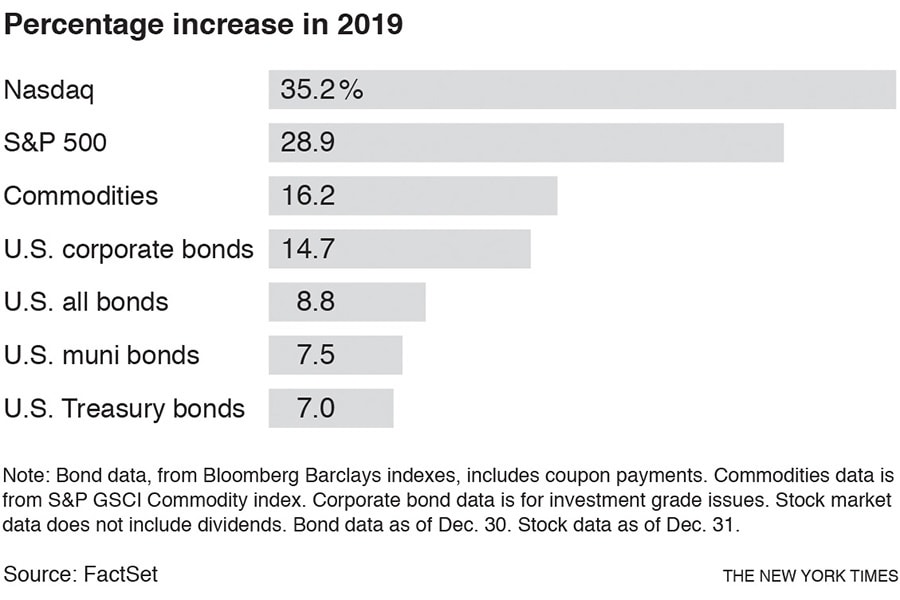

After a 0.3% gain on Tuesday, the S&P 500 index ended 2019 up 28.9%, its strongest performance since 2013 and one of the best in decades. Broad indexes of the American bond markets are up nearly 9%. Gold jumped 18.7% and silver about 15%, and other commodities were also up. (Futures prices for hogs, in case that had been your pick, gained about 17%.)

It was a remarkable across-the-board rally of a scale not seen in nearly a decade. The cause? Mostly a head-spinning reversal by the Federal Reserve, which went from planning to raise interest rates to cutting them and pumping fresh money into the financial markets.

“Rarely in my career has everything worked simultaneously,” said Mark Vaselkiv, chief investment officer for fixed income at the asset management firm T. Rowe Price.

Analysts at Ned Davis Research tracked eight types of investments — large and small domestic stocks, developed and emerging market stocks, Treasuries, corporate bonds, commodities and real estate — going back to 1972. In 2019, all eight categories generated profits and — for the first time since 2010 — each rose 5% or more.

In fact, the gains were much better than that, with a median gain of 21% for the eight asset classes.

The Nasdaq composite index is up more than 35%, its best showing since 2013. Small-cap stocks are up about 24%, their best gains since 2013. A gain of more than 14% for high-quality American corporate bonds is the best showing since 2009. European shares, up 23%, are likewise having their best year in a decade.

Those gains can have a knock-on effect on the economy outside Wall Street, creating a feedback loop that helps encourage more buying.

The rally in bond prices, which move in the opposite direction from yields, has helped keep borrowing costs low for companies, municipalities and the federal government. And, along with an unemployment rate at 50-year lows, the stock market’s surge is supporting spending by consumers, who are the main driver of growth in the American economy.

Not everyone benefits when markets rise like this. Some investors bet on certain markets to fall, either because they think they are due for a drop or because they expect that the traditional relationships among different assets — where some go up so others go down — will help them hedge their portfolios.

(And we should note that not absolutely everything rose in 2019: Natural gas was a losing bet. So was cobalt. And even a rising stock market contains more than a few sinking ships. Macy’s, for instance, dropped more than 40%.)

There’s little reason to assume that these kinds of uniform gains will continue. Usually, different investments are driven by different kinds of dynamics: Stock prices, for example, have climbed at a faster clip than expectations for profit growth. That means the market is looking more and more overvalued. If corporate profits don’t catch up, stocks could stumble.

And bond markets have soared, but increasing loads of corporate debt could prompt investors to sell if they think these companies are taking on too much risk.

One factor behind the rise in bond prices in 2019 was a growing worry about the impact of the trade war. Even though the trade war isn’t over, Washington and Beijing have reduced the tension between them, and the economy isn’t faring as poorly as people had feared. (Good for stocks, but, perhaps, bad for bonds.)

For now, concerns about such market fundamentals seem to be set squarely on the back burner, after the Fed reinvigorated risk-taking in the markets by cutting interest rates three times out of concern that the trade war and a global growth slowdown would drag the U.S. economy lower.

The cuts were an about-face for the Fed, which in 2018 raised interest rates four times and unnerved financial markets along the way.

In fact, instead of the rise in asset prices that investors enjoyed in 2019, the previous year was marked by a uniform decline, reflecting worries that higher interest rates and the trade war would tip the economy into a recession.

The central bank also started to buy securities again in 2019, pumping about $60 billion into the financial markets every month. The most recent round of purchases has been billed as a technical fix — instead of one meant to bolster the economy — but bond-buying programs put in place after the financial crisis were widely credited for driving markets up sharply.

For much of the last decade, similar moves by the Fed aimed at shoring up economic growth helped supercharge returns in financial markets. Most close observers think this is precisely what happened in 2019.

“When people look back on this year, they’ll say the Fed did this,” said Evan Brown, head of multi-asset strategy at UBS Asset Management.

©2019 New York Times News Service