Intel's culture needed fixing. Its CEO is shaking things up

Robert Swan was promoted to the top job a year ago and his revamp efforts involve everything from the designing of chips to basic communication between teams

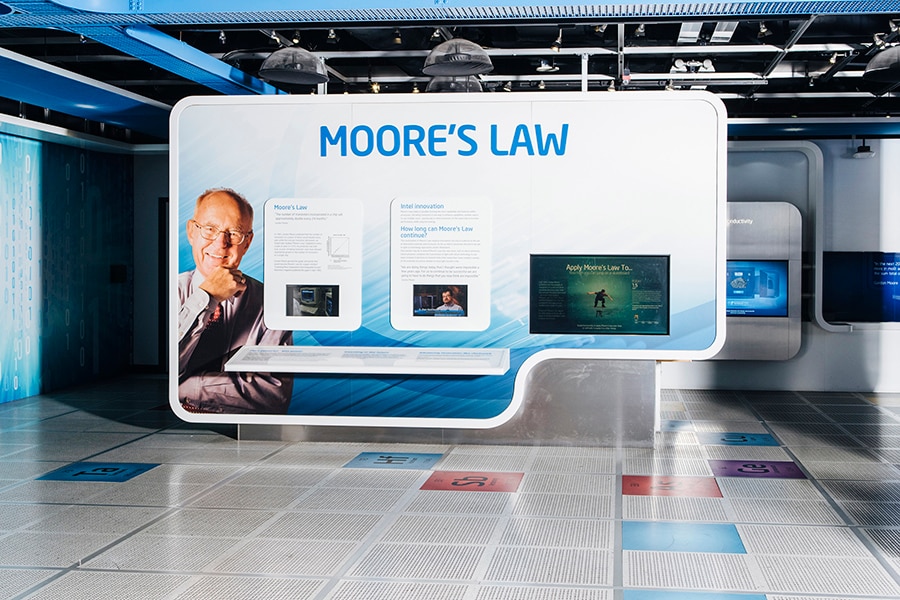

A display at Intel Museum that includes a silicon wafer using 32-nanometer production technology in Santa Clara, Calif. on Jan. 28, 2019. Intel maintained a near-religious reverence for Moore’s Law, which refers to the co-founder Gordon Moore’s oft-quoted observation that the number of transistors on a chip can be doubled every two years or so. (Cayce Clifford/The New York Times)

A display at Intel Museum that includes a silicon wafer using 32-nanometer production technology in Santa Clara, Calif. on Jan. 28, 2019. Intel maintained a near-religious reverence for Moore’s Law, which refers to the co-founder Gordon Moore’s oft-quoted observation that the number of transistors on a chip can be doubled every two years or so. (Cayce Clifford/The New York Times)SANTA CLARA, Calif. — Since last spring, workers at Intel who turned on their corporate laptops or wall displays inside the company’s more than 1,000 conference rooms have seen a new tagline: “One Intel.”

A plea for unity might seem surprising at a company that has long had a singular mission of making semiconductors. But Intel had a hidden problem, said Robert Swan, its chief executive: Its culture badly needed an overhaul, and its 110,000 employees needed to confront issues more openly.

“If you have a problem, put it on the table,” said Swan, 59, who was promoted to the top job a year ago and has since embarked on a campaign to shake up the Silicon Valley giant.

His efforts remain a work in progress. But the changes — some of which lean on the precepts of Andrew S. Grove, the former Intel chief executive who coined the credo “Only the paranoid survive” — are Intel’s biggest attitude adjustment in decades.

For years, Intel’s near-monopoly in chips allowed it to dictate how and when computer-makers improved their products. But Swan is targeting additional markets, which means Intel will need input from customers to succeed in them.

“They were driving everything, and the world was simply having to follow them,” said Robert Burgelman, a management professor at Stanford University, who has written about Intel and for decades taught a class with Grove. “Where Bob is doing a great job is to give them some modesty.”

Intel had begun modifying some procedures before Swan became chief executive, but his emphasis on changing the 51-year-old company’s culture has sharply accelerated progress, executives said. The revamp is affecting everything from the designing of chips, which act as the brains of computers, to basic communication between teams.

Intel is now developing products with input from multiple groups, something it had not really tried before. To speed product design, Swan’s lieutenants have set up smaller teams and broken up chips into modular blocks of circuitry. And they have improved collaboration between manufacturing and design engineers, who had been estranged in recent years.

“They tell us what we need to know, and we tell them what they need to know,” said Jim Keller, a senior vice president leading chip design efforts. “That’s a big transformation.”

Swan, who spent nine years at eBay and 15 years at General Electric, joined Intel in 2016 as chief financial officer. He became interim chief executive in June 2018, replacing Brian Krzanich, who stepped down after the disclosure of a past affair with a subordinate. Swan got the job permanently in January 2019.

He immediately had a to-do list. Intel had been grappling with slowing growth. More recently, the $237 billion company has been dealing with uncertainty from the coronavirus; China accounted for about 28% of Intel’s $72 billion in revenue last year. The uncertainty about the virus is what caused stock markets around the world to plunge last week.

Intel also had deeply rooted problems reflecting its years of dominance, Swan said. Managers, complacent about competition, battled internally over budgets. Some of them hoarded information, he said.

Most significant, a cultural touchstone had turned into a trouble spot. Intel maintained a near-religious reverence for Moore’s Law, which refers to the co-founder Gordon Moore’s oft-quoted observation that the number of transistors on a chip can be doubled every two years or so.

Yet Intel’s push to reduce a chip’s circuit dimensions to 10 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, wasn’t achieved until mid-2019 — even though the advance had once been expected as early as 2015.

The delay exposed Intel’s overconfidence. Its engineers had promised to pack 2.7 times more transistors in the same space, a risky leap requiring novel production techniques, said Mike Mayberry, Intel’s chief technology officer. And leaders of chip manufacturing gave top management little data about problems, slowing the search for a solution, Swan said.

All of that cost Intel. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., or TSMC, and Samsung grabbed the Moore’s Law lead and began making chips for Intel rivals. Delayed from using the new production process — and facing unexpectedly high demand for some products — Intel didn’t have production capacity to make enough chips for PCs. Swan had to repeatedly apologize for the shortages.

The stumbles had a silver lining of sorts: They proved to Intel’s employees that change was needed. The crises will be among “the best things that ever happened to the company,” Swan said, adding that dealing with the aftermath was not exactly fun.

Intel began making changes. Venkata Renduchintala, an Intel group president who oversees most product design, ordered a three-month “timeout” in 2018 so engineers could retrace their steps and revise the 10-nanometer production recipe.

Renduchintala, who is known as Murthy, also pushed more inclusive ways to design products. One example was Lakefield, the code name for an unusual bundle of semiconductors, created by stacking multiple chips to save space. To conceive it, design teams from different groups around the company pitched in ideas, which broke “the rules of how we’ve ever done a product,” Renduchintala said.

Intel recruited Keller, an engineer known for stints at Apple and an Intel rival, Advanced Micro Devices, in July 2018 to spearhead other design changes. He set up small teams, instead of the large ones that typically designed most of the chip circuitry from scratch to maximize computing performance. Some of the new teams were directed to develop standard blocks of circuitry that could be reused in different products so engineers could work independently without waiting for others to finish their portions of a chip.

That helped reduce the time needed to make and test chip design changes from weeks to days, Keller said. Creating an entire chip design can now be as much as three times faster, he said.

Swan kicked the changes into a higher gear in an open letter after he was named chief executive last year. Besides unveiling the “One Intel” slogan, he exhorted workers to be bolder, to be more attentive to customers and to honor “truth and transparency,” which was code for being more honest about facing problems and collaborating more.

The relationship between Intel’s chip designers and manufacturing had been particularly strained, Swan said. The manufacturing team, based in Oregon, had been slow to share technical details with the designers out of a desire to prevent leaks that could threaten Intel’s perceived tech lead, current and former executives said.

In contrast, TSMC, the Taiwanese rival, regularly shared data about its manufacturing technology with external designers and incorporated their suggestions.

To spur similar collaboration, Renduchintala set up a new oversight committee in September 2018 with three executives from the design group and three from manufacturing. Their information flow really picked up after Swan began pushing his cultural goals, executives said.

Swan’s mantras also led Intel managers to analyze competing products more closely, improve relations with partners and speed decision-making, executives said.

Sundari Mitra, a vice president who worked at Intel 30 years earlier and returned in 2018, said she had previously encountered bureaucratic traits like too many product review meetings. Taking Swan’s message to heart, she is cutting those down, while encouraging employees to begin presentations by listing problems rather than what was working well.

If executives “keep dinging them on what is not happening,” which was a tendency in the past, “this culture is not going to change,” she said.

For all the effort, financial benefits of the changes may take years to appear. Yet Swan keeps trying new tactics, including recently linking employee bonuses partly to “One Intel” improvements measured by employee surveys.

“We have the smartest people in the world,” Swan said. The question remains, he said, “how do you get them rowing in the same direction?”

©2019 New York Times News Service