George Floyd: Officers charged in death not likely to present united front

Facing decades in prison and a bail of at least $750,000, two former Minneapolis officers blamed Derek Chauvin, and a third has cooperated with investigators, their lawyers said

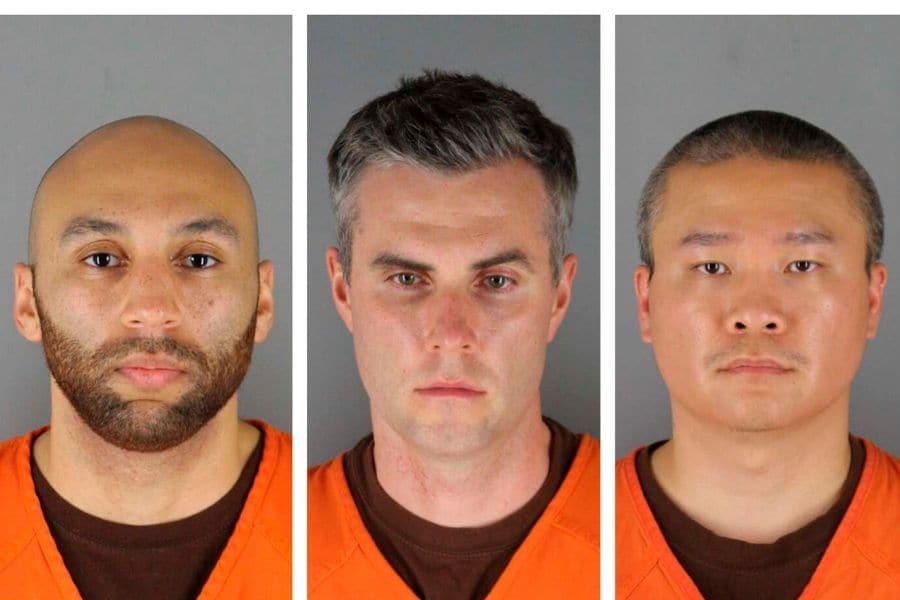

A combination of photos provided by the Hennepin County Sheriff's Office shows, from left, J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao. Minnesota officials charged the three former police officers on Wednesday, June 3, with aiding and abetting murder, court records show, in the death of George Floyd. (Hennepin County Sheriff's Office via The New York Times)

MINNEAPOLIS — Two of the former police officers charged with aiding and abetting in the killing of George Floyd turned on the senior officer accused in the case, making for an extraordinary court appearance Thursday afternoon. A third officer was cooperating with authorities, a sign that the four fired officers would not be presenting a united front.

Facing 40 years in prison and a bail of at least $750,000, former officers Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng, both rookies, blamed Derek Chauvin, the senior officer at the scene and a training officer, their lawyers said in court. The lawyer for Tou Thao, another former officer charged in the case, said his client had cooperated with investigators before they arrested Chauvin.

Chauvin, a white 19-year veteran, was captured on a graphic video on May 25 kneeling for almost nine minutes on the neck of Floyd, who was African American, as the other three officers aided in the arrest.

Chauvin, 44, who did not appear in court Thursday, faces the most serious charges of the four men — second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

©2019 New York Times News Service