At Boeing, CEO's stumbles deepen a crisis

It was a rare dressing-down for the leader of one of the world's biggest companies, and a sign of the deteriorating relationship between Muilenburg and the regulator

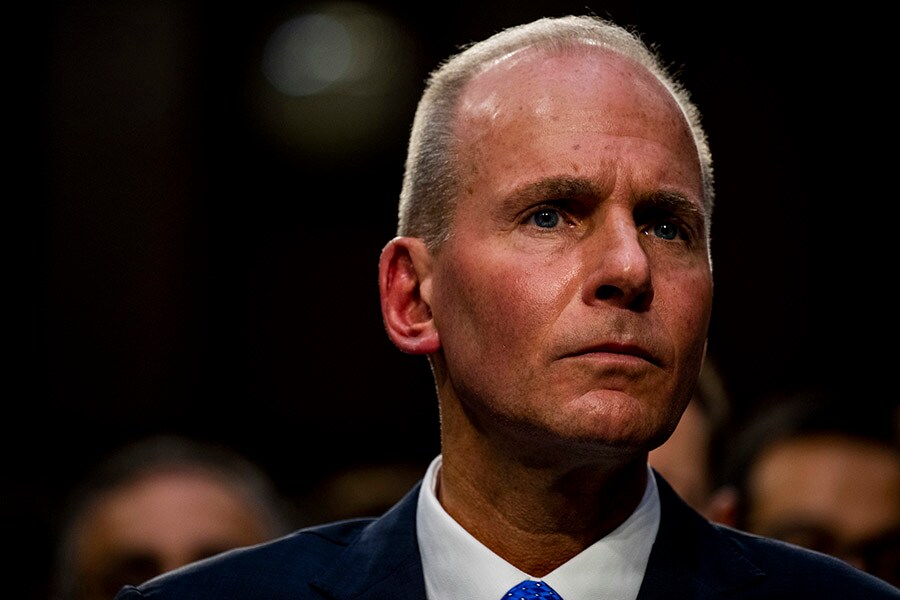

Dennis Muilenburg, the chief executive of Boeing, testifies on Capitol Hill in Washington, Oct. 29, 2019. Muilenburg’s handling of the 737 Max grounding after two fatal crashes has angered lawmakers, airlines, regulators and victims’ families. (Anna Moneymaker/The New York Times)

Dennis Muilenburg, the chief executive of Boeing, testifies on Capitol Hill in Washington, Oct. 29, 2019. Muilenburg’s handling of the 737 Max grounding after two fatal crashes has angered lawmakers, airlines, regulators and victims’ families. (Anna Moneymaker/The New York Times)In a tense, private meeting last week in Washington, the head of the Federal Aviation Administration reprimanded Boeing’s chief executive for putting pressure on the agency to move faster in approving the return of the company’s 737 Max jet.

This was the first face-to-face encounter between the FAA chief, Stephen Dickson, and the executive, Dennis A. Muilenburg, and Dickson told him not to ask for any favors during the discussion. He said Boeing should focus on providing all the documents needed to fully describe the plane’s software changes according to two people briefed on the meeting.

It was a rare dressing-down for the leader of one of the world’s biggest companies, and a sign of the deteriorating relationship between Muilenburg and the regulator that will determine when Boeing’s most important plane will fly again.

The global grounding of the 737 Max has entered its 10th month, after two crashes that killed 346 people, and the most significant crisis in Boeing’s history has no end in sight. Muilenburg is under immense pressure to achieve two distinct goals. He wants to return the Max to service as soon as possible, relieving the pressure on Boeing, airlines and suppliers. Yet the company and regulators must fix an automated system known as MCAS found to have played a role in both crashes, ensuring the Max is certified safely and transparently. Caught in the middle, Muilenburg has found himself promising more than he can deliver.

After the crashes, but before the plane was grounded, Muilenburg called President Donald Trump and expressed confidence in the safety of the Max. He has repeatedly made overly optimistic projections about how quickly the plane would return to service, pushing for speedy approval from regulators. The constantly shifting timeline has created chaos for airlines, which have had to cancel thousands of flights and sacrifice billions of dollars in sales.

In his few public appearances, Muilenburg’s attempts to offer a sincere apology for the accidents have been clumsy, prolonging Boeing’s reputational pain. His performance has left lawmakers irate. The families of crash victims, convinced the company does not care about their loss, have repeatedly confronted him with posters of the dead.

The missteps led Boeing to one of the most consequential decisions in its 103-year history, when it announced Dec. 16 that it was temporarily shutting down the 737 factory, a move that has already begun rippling through the national economy.

The Max is Boeing’s best seller, with tens of billions of dollars in future sales at stake. Boeing stock has fallen 22% in this crisis, costing the company more than $8 billion and spreading pain throughout a supply chain that extends to 8,000 companies. Friday, Spirit AeroSystems, which makes the Max fuselage, said it would stop production of the part next month.

“Throughout this process our No. 1 priority has been safety,” Gordon Johndroe, a Boeing spokesman, said in a statement. “We have learned a lot this year and our company is changing.”

Last week, when Trump called Muilenburg to discuss Boeing’s problems, the chief executive assured the president that a production shutdown would only be temporary.

But Boeing still faces serious hurdles. The company has not delivered a complete software package to the FAA for approval. In recent simulator tests, pilots did not use the correct emergency procedures, raising new questions about whether regulators will require more extensive training for pilots to fly the plane or whether the procedures needed to be changed, according to two people briefed on the matter.

And Friday, a new space capsule Boeing designed for NASA failed to reach the correct orbit, another blow to company morale and a setback for the U.S. space program.

“If it was my call to make, Muilenburg would’ve been fired long ago,” Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., the chairman of the House Transportation Committee investigating Boeing, said in an email. “Boeing could send a strong signal that it is truly serious about safety by holding its top decision-maker accountable.”

From the earliest days of the grounding in March, shortly after the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 and months after the first Max crash, off Indonesia, Muilenburg tried to put the episode behind him as swiftly as possible, telling airlines it would last just weeks.

“By the time April rolled around, Boeing was telling us next week, next month,” Gary Kelly, the chief executive of Southwest Airlines, said in an interview. “We were a week away, weeks away, three weeks away.”

That misplaced optimism made it impossible for airlines including Southwest, which is Boeing’s biggest 737 customer, to reliably plan their routes. “It was really creating havoc,” Kelly said.

In August, regulators from Europe, Canada and Brazil flew to Seattle and joined FAA officials for a meeting with Boeing. They were expecting to review reams of documentation describing the software update for the Max. Instead, Boeing representatives offered a brief PowerPoint presentation, in line with what they had done in the past. The regulators left the meeting early.

“We were looking for a lot more rigor in the presentation of the materials,” said Earl Lawrence, the head of the FAA’s aircraft certification office. “They were not ready.”

With delays mounting, Muilenburg missed a chance to smooth things over with key customers. In September, he attended a gathering of a club of aviation executives called Conquistadores del Cielo at a ranch in Wyoming, according to two people familiar with the trip. As the group bonded while throwing knives and drinking beers, Muilenburg took long bike rides by himself. It was typical behavior for Muilenburg, an introverted engineer who prefers Diet Mountain Dew to alcohol, but it left other executives baffled.

October brought a string of bad news for Muilenburg. The board stripped him of his title as chairman, a stinging rebuke of his leadership. The decision, the board said, would allow him to focus on the single most important job at the company: bringing the Max back to service.

About two weeks before Muilenburg testified in front of Congress for the first time, the company disclosed to lawmakers instant messages from 2016 in which a Boeing pilot complained that the system known as MCAS, which was new to the plane, was acting unpredictably in a flight simulator. Boeing discovered the instant messages in January, but Muilenburg did not read them at the time, instead telling the company’s legal team to handle them.

The messages included the pilot saying he “basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly).”

When Dickson learned of the messages in October, he sent a one-paragraph letter to Muilenburg demanding an explanation for “Boeing’s delay in disclosing the document to its safety regulator.”

Muilenburg and Dickson, who took over the FAA this summer, spoke for the first time later that day. Muilenburg said Boeing hadn’t told the FAA about the messages out of concern that doing so would interfere with a criminal investigation being conducted by the Justice Department, according to two people briefed on the call.

Dickson said the lack of transparency would only increase the regulator’s scrutiny of the company.

Still, Muilenburg continued to project confidence, telling investors on an earnings call in October that he expected regulators to begin approving the Max by the end of the year. The company had just fired Kevin McAllister, chief executive of Boeing’s commercial division who had been overseeing work on the Max.

Despite Muilenburg’s assurances, airline discontent was growing. The next day, American Airlines joined a chorus of Boeing customers complaining about the growing costs of the Max crisis. Doug Parker, American’s chief executive, said on a call with investors that he was working to “ensure that American is compensated for the lost revenue that the Max grounding has caused, the missed deadlines and extended grounding.”

“We’re working to ensure that Boeing shareholders bear the cost of Boeing’s failures,” Parker added. “Not American Airlines’ shareholders.”

In two days of congressional hearings at the end of October, Muilenburg faced withering criticism from lawmakers, who told him to resign or take a pay cut. Muilenburg said it was up to the board to make decisions about his multimillion-dollar compensation. He invoked his upbringing on an Iowa farm so many times that he elicited jeers from family members of crash victims who were present.

In an interview on CNBC after the hearings, the chairman of Boeing’s board, David Calhoun, said the board was confident in its chief executive.

“From the vantage point of our board, Dennis has done everything right,” Calhoun said. “If we successfully get from where he started to where we need to end up, I would view that as a very significant milestone and something that speaks to his leadership and his courage and his ability to execute and get us through this.”

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Muilenburg continued to press the FAA. In early November, he called Dickson to ask whether he would consider allowing the company to begin delivering airplanes before they were cleared to fly. The administrator said he would look into it but made no commitments, according to an FAA spokesman.

In an apparent misunderstanding, Muilenburg took the call as a green light. The next Monday, the company put out a statement saying it could have the plane to customers by the end of the year.

Dickson told colleagues that he had not agreed to that timeline and felt as though he was being manipulated, according to a person familiar with the matter. That week, he put out a memo and a video urging employees to resist pressure to move quickly on the Max approval.

This month, anxiety levels rose at Boeing’s factory in Renton, Washington. Several key tests had not yet been completed, and European regulators would soon leave work for the holidays and not return until the beginning of January. In calls with FAA officials, Boeing engineers began to float an idea for speeding the process: Perhaps the company should ask the agency to break with its foreign counterparts and approve the Max alone?

The suggestion alarmed some FAA officials, who worried that approving the Max without agreement from other regulators would be untenable, according to two people familiar with the matter. When they called Dickson to tell him of Boeing’s plans, he balked at the suggestion and eventually the company backed down.

A week later, Dickson brought Muilenburg into the agency’s Washington headquarters for their first in-person meeting.

There, Dickson said he had done the math, and there was no way the Max could fly by the end of the year.

When Muilenburg brought up the logistics of delivering Max jets to customers, Dickson would not discuss the issue, two people familiar with the matter said. Boeing’s representatives said they might need to consider temporarily shutting down production. Dickson told them to do what they needed to do, saying the agency was focused on conducting a thorough review.

Four days later, Boeing announced it would bring the 737 factory to a halt. There was no discussion of removing Muilenburg as chief executive at last week’s board meeting in Chicago where the shutdown was debated, according to three people briefed on the meeting.

The challenges facing Muilenburg extend beyond returning the Max to service and the botched space capsule launch Friday. The FAA is aware of more potentially damaging messages from Boeing employees that the company has not turned over to the agency. Other important planes are behind schedule. New defects have been found on older models of the 737. Boeing lost two major pieces of business to Airbus, its European rival, this month.

“This hasn’t been their best and finest hour,” said Kelly, the Southwest Airlines chief executive. “There’s mistakes made and they need to address those.”

With the anniversary of the Ethiopian accident approaching in March, Boeing recently asked a representative for the families of crash victims if it would be appropriate for Muilenburg to attend the memorial. They said no.

“He is not welcome there,” said Zipporah Kuria, whose father, Joseph Waithaka, was killed in the second crash. “Whenever his name is said, people’s eyes are flooded with tears.”

©2019 New York Times News Service