A teacher, his killer and the failure of French integration

For generations, public schools assimilated immigrant children into French society by instilling the nation's ideals. The beheading of a teacher has raised doubts about whether that model still works

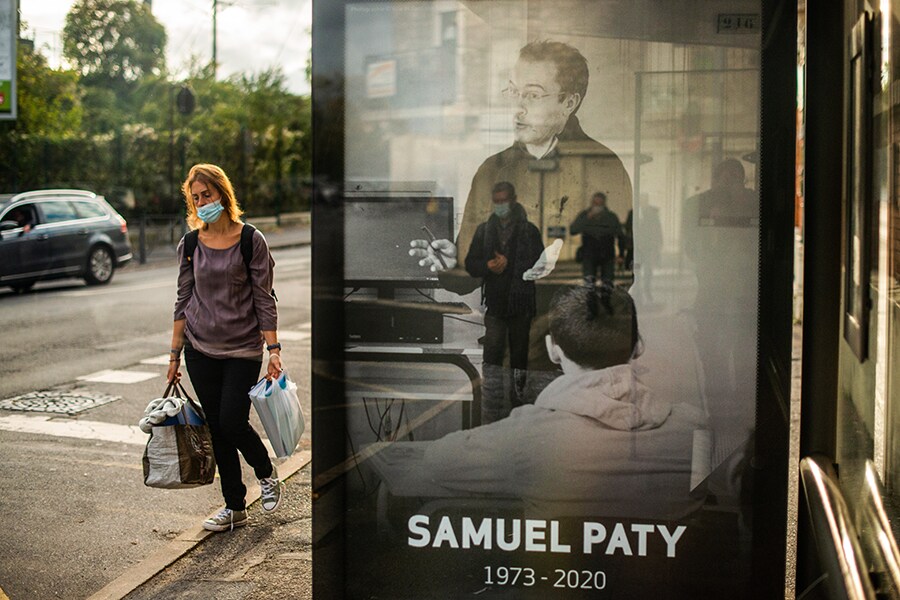

A photo at a bus stop in memory Samuel Paty, who was beheaded after showing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in a class on free speech, in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, France, Oct. 22, 2020. For generations, public schools assimilated immigrant children into French society by instilling the nation’s ideals. The beheading of Paty has raised doubts about whether that model still works. (Dmitry Kostyukov/The New York Times)

A photo at a bus stop in memory Samuel Paty, who was beheaded after showing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in a class on free speech, in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, France, Oct. 22, 2020. For generations, public schools assimilated immigrant children into French society by instilling the nation’s ideals. The beheading of Paty has raised doubts about whether that model still works. (Dmitry Kostyukov/The New York Times)

ÉVREUX, France — They could have easily shared the same classroom — the immigrant teenager and the veteran teacher known for his commitment to instilling the nation’s ideals, in a relationship that had turned waves of newcomers into French citizens.

But Abdoullakh Anzorov, 18, who grew up in France from age 6 and was the product of its public schools, rejected those principles in a horrific crime that shocked and enraged France. Offended by cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad shown in a class on free speech given by the teacher, Samuel Paty, 47, the teenager beheaded him a week ago with a long knife before being gunned down by police.

France has paid national homage to Paty because the killing was seen as an attack on the very foundation — the teacher, the public school — of French citizenship. In the anger sweeping the nation, French leaders have promised to redouble their defense of a public educational system that plays an essential role in shaping national identity.

The killing has underscored the increasing challenges to that system as France grows more racially and ethnically diverse. Two or three generations of newcomers have now struggled to integrate into French society, the political establishment agrees.

But the nation, broadly, has balked at the suggestion from critics, many in the Muslim community, that France’s model of integration, including its schools, needs an update or an overhaul.

©2019 New York Times News Service