South Africa: Between Two Worlds

South Africa is slowly shaking off its Western leanings. It’s finding new reference points in emerging markets that share similar issues

Amid swarming tourists and global media attention, for South Africa right now there seems to be just one goal — the Soccer World Cup. Last minute preparations are in full swing. The government is anxious. South Africans are ecstatic. And businesses are hopeful.

However, euphoric moments don’t change ground realities. Underneath there are many issues that this young democracy is grappling with. To get a flavour, go no further than Sandton, an upmarket suburb in Johannesburg. BMWs, Mercedes and Audis race on its layered smooth expressways. Glitzy digital hoardings and swanky hotel towers dot its skyline. One envies its expansive office complexes, beautiful residential complexes and well manicured greens. In the middle of Sandton, the sprawling Nelson Mandela Square is buzzing. Tourists pose in front of the giant bronze Mandela statue. Its European style open bars are crowded. With two big malls, huge multi-storeyed parking area, the square hosts some of the top notch global retailers and designer labels.

Sandton feels both sophisticated and modern. Except, it isn’t.

At road crossings, blacks beg for money, food or even garbage from your car. Houses look like

fortresses with high walls and electric fences. Car jacking is common and drivers secure their locks before starting. At the bustling Mandela Square poor youths trail tourists asking for money. In a country with one of the highest crime rates, you often cringe, feeling insecure and anxious.

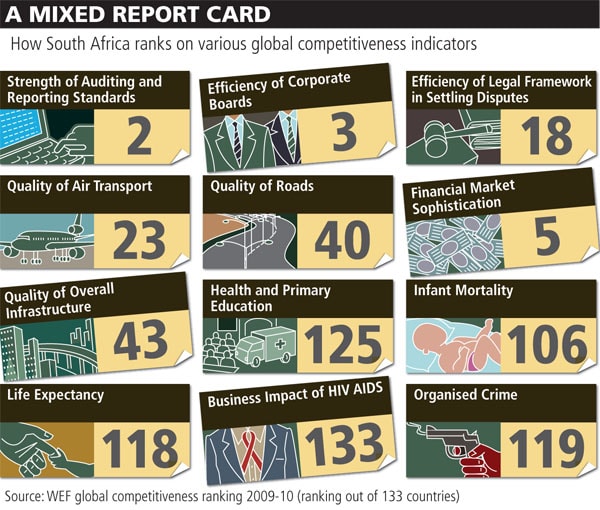

South Africa looks like a First World country with Third World challenges. For very long, ruled by the whites, the country looked for inspiration to the classic West. And the impact is visible everywhere. South Africa has one of the most sophisticated financial services. Its aviation industry is fairly evolved. Its expressways aren’t far behind the German autobahns. The aesthetics of historical Europe show up in its buildings and structures.

But in the post apartheid era, South Africa is in search of a new reference point. Bogged by socio-economic challenges and nudged by a desire to play a bigger role in the world today, the country’s Third World underpinnings are significantly influencing the way it thinks, plans and positions itself on the global map. This subtle yet significant shift has some serious political, economic and social implications in the long run. “The gaze of policy makers has moved to the East. They are looking at the future and asking what should be our agenda,” says Adam Habib, deputy vice chancellor, University of Johannesburg.

The Shift

The evidence is clear. Take trade data as an indicator. Exports to and imports from its dominant trade partners like Germany, the UK and the US have been consistently shrinking (relatively) over the last decade even as that from China and India have been rising, says Gunajit Kalita, researcher, Regional Impact, ICREAR. India is among the top 10 trading partners today — there was zero trade in 1994. More importantly, investments from Asia have been rising. In the biggest deal, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China acquired 20 percent stake in the South African Standard Bank for $5.6-billion, making it the largest FDI into South Africa. Over 100 Indian companies have so far invested around $3.5 billion into the country. Kirloskars and Godrej have been making acquisitions here.

But one can discern more nuanced shifts to the East as one talks to experts on South Africa. Earlier, B-Schools in South Africa would focus on case studies in the West; now they are bringing in case studies and business models of the East. Earlier, executive education programmes would typically take them to London and New York for immersion sessions; today it’s often to Mumbai and Shanghai. On the investment councils typically executives from Western MNCs like Oracle would be appointed; today it is companies like the Tatas who are being considered.

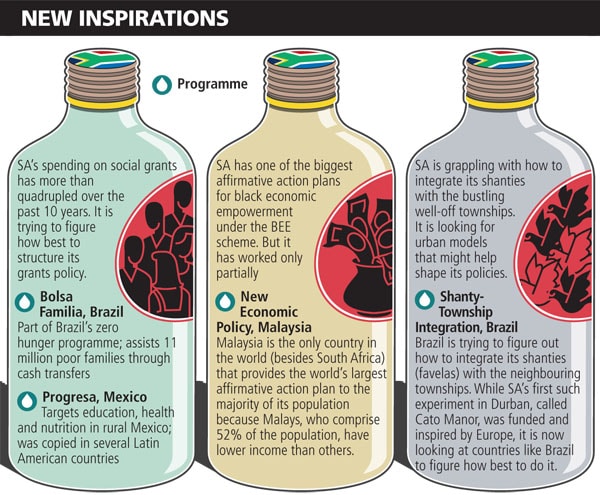

Even for some of the big policy issues like affirmative action, low-cost housing and social grants scheme, South Africa is increasingly looking at the emerging markets of Brazil, India, Mexico, China for ideas and learnings. More and more bilateral ties are being stitched up with these countries. Global platforms for banding together are being worked upon. The South-South dialogue under IBSA (India-Brazil-South Africa) is progressing well. During the Copenhagen climate talks last December, Brazil, South Africa, India and China jointly led the emerging markets agenda to critically influence the outcomes. “We are beginning to see conversations across a different set of boundaries,” says Habib.

Infographic by Malay Karmakar

The Challenges

This shift has a lot to do with how South Africa sees itself today, the challenges it is grappling with and the role it sees for itself in future. It’s a rainbow nation with whites, blacks, Asians all living together. But a vast majority of its 49 million people — about 80 percent — comprise blacks. Nowhere in the world is the contrast between a minority rich and majority poor as stark as in South Africa. Not even in India, the land of inherent contradictions. In India, a vast middle class cushions the inequality effect; here, the middle class is small.

After 1994 with the end of apartheid, the South African government has been working hard to bridge the divide between blacks and whites. It launched a slew of schemes. Its affirmative action plan, called Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), gives black workers and entrepreneurs (the definition includes Africans, mixed-race people and Indians) preferential treatment in government jobs and tenders. To push for wider enterprise ownership, it also gives extra credit to companies on how blacks are represented on their boards, in senior positions, and on employees’ ownership stake. This has helped, but has also created a small band of black elites, called “tender-preneurs”. Widespread black empowerment is still a distant dream. “Policy documents are all very good. Problem is execution, implementation,” says Stephen Gelb, director, Edge Institute, South Africa.

The official unemployment rate in South Africa is among the highest at 25 percent. And this is a conservative estimate, most experts say. Many blacks, out of a job for a long time, no longer show up in official statistics. The flood of refugees — thousands from Zimbabwe alone — only makes things worse. Not surprising that the crime rate is among the highest in the world. The security business in South Africa is said to be its biggest industry; most well off South Africans invest heavily in securing their cars and homes.

Fifteen years after the end of apartheid, extreme poverty persists, shanties dot the landscape, child mortality is high, and so is the number of children out of school. All this, despite the fact that the South African government is putting a lot of resources behind fixing these issues.

Amid economic crisis, the government has let the fiscal deficit expand to 7.6 percent of the GDP to continue funding its social and infrastructure programmes. Spending on social grants has more than quadrupled over the past 10 years, now reaching almost 4 percent of its national income — more than nearly any other developing country, says Michael Samson, research director, Economic Policy Research Institute. Over 12 million children, for example, receive grants that support their nutrition, education, health and well-being. Ten years ago this was less than a million.

South Africa’s substantive welfare agenda makes it lean naturally towards other emerging markets. In policy and spending, it might feel closer to countries like India and Brazil. It realises that the answers will come from other nations with similar issues.

Infographic by Malay Karmakar

For example, its ambitious social grants policy is working but is not as effective. “It leans on “means testing” (to vet eligible citizens) which is a Western idea,” says Julian May, professor, School of development studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal. One has to first get his or her income tested before he/she becomes eligible for any grant. “Often it costs so much more to do the testing,” says May. The country is looking to learn from the experiences of Brazil and Mexico on this.

Economic Realities

The shift in reference point is also driven by serious economic considerations. While in absolute numbers the US and Europe dominate Africa as trading partners, trade with Asia is rising exponentially. Asia’s exports to Africa have been rising annually by 18 percent; African imports have roughly doubled since 2000. “Asia is set to become the dominant economic presence in Africa,” says Habib. The future national footprints with the most lasting legacy in Africa are likely to be those of the United States, China and India, he says. South Africa, the de facto leader in the African continent, is keenly aware of this big shift in global economic sweepstakes and wants deeper relationships with the emerging markets.

The structure of the South African economy too is making things difficult for the government. According to the 2008 data available, the primary sector (agriculture, fishing and mining) contributes just around 8 percent to the GDP. The secondary sector (manufacturing, construction and electricity) contributes around 21 percent. And tertiary sector (trade, transport, finance and real estate) contributes around 62 percent to the GDP. The economy is largely driven by private consumption, which in turn is credit driven.

“There are two sectors I see having the capacity to absorb the South African labour — manufacturing and mining,” says Tony Twine, economist at Econometrix. The country will have to figure ways to fix two things: How to exploit its primary resources like minerals and agriculture to move up the value chain. And two, explore better ways to create jobs at the low end of skills chain. “With high unemployment, most of our workforce is unemployable in a 21st century economy,” adds Twine. It doesn’t help that primary, secondary and tertiary education in South Africa is facing significant challenges and needs enormous fixing to be able to train and equip its people for the workplace. “Large parts of our population are not geared to cater to a modern economy,” says Derick Boshard, managing partner, Heidrick & Struggles.

Perhaps in all these cases, South Africa will need to look at other emerging countries for learning and inspirations.

The Geopolitical Spin

In relative terms, the South African economy is small, ranked 31 at $277 billion. Even among emerging markets (GDP on purchasing power party — ppp — terms), China, India, Brazil, Russia, Mexico and Turkey rank much higher in their economic heft. Yet South Africa plays an important role in the global arena. Often people call it the S in the BRICS. If South Africa today wields disproportionate weight in international diplomacy, it is because of its geopolitical significance. It is the largest, most industrialised and developed country in Africa and in some ways is the instinctive leader for the African countries. While they understand Africa well, “they also have friends in the right place. South Africa’s good links with the West helps it to organise finances, make connections,” says Dana D. Smith, MD, Marker Global.

For global powers, Africa is the new battleground. The need to diversify their oil source away from the Gulf and hunger for commodities and minerals is pushing countries like the US and China to get deeply entrenched there. South Africa too has its economic interests. It has continuously had trade surplus with the African continent and also sells a significant proportion of its industrial output here. Amid this scramble, Africa needs to leverage its collective might to avoid exploitative tendencies of the past. Clearly, while South Africa is the best entry point for companies looking for a toe-hold into the African continent, it is also the best country to represent/lobby for the African countries.

South Africa increasingly realises that it will need to band with other emerging countries to add some grist to its global might. African concerns on most issues will align better with the developing world. This was visible during the recent Copenhagen climate talks. All African countries united under Africa Union to represent their collective voice. As part of the BASIC group (Brazil, SA, India and China — representing the concerns of the developing world) they emerged as an important bloc dictating the agenda. Already, pacts like IBSA focus on South-South co-operation among India, Brazil, SA at multiple levels like health, anti-corruption, human development and climate change.

“Issues of poverty, building infrastructure, competing with world class companies along with dealing with people who are poor — Brazil, India and China today are more plausible reference points,” says Ann Bernstein, founding director, centre for development and enterprise.

India’s Role

While the Chinese engagement in Africa and South Africa is largely on the back of the country’s money power in buying/building assets, India has a different strategy, says Vikram Doraiswamy, the Indian counsel general in Johannesburg. India is assisting South Africa in transforming its educational system. It is setting up vocational training colleges and is is helping SA beef up science and math education.

India is also involved in capacity building in dealing with inequality. Under the $2-billion International Technical Co-operation Programme (ITEC), India has been training South African scientists in various areas. Academic linkages are being strengthened. The Indian government has facilitated the process by hosting the vice chancellors of several prominent South African universities. A Centre of Indian Studies in Africa (CISA) was launched in September 2008 at the University of the Witwatersrand, the first ‘India focus’ centre in Africa.

Unlike the Chinese, a lot of India involvement in South Africa is led by the private sector. Over 100 Indian companies are present here. It’s a natural fit given Indian firms’ low-cost models and expertise in delivering to the bottom of the pyramid. It helps that many of them have worked with the Indian government on a large number of e-governance projects and have the ambition, expertise and capacity to cater to South African needs.

Companies like TCS, NIIT, Sankhya are already involved in the education space; so are low-cost generic drug manufacturers like Ranbaxy and Dr Reddy’s. Dealing with some of the developing world diseases like malaria and AIDS, tech tie-ups are on the cards among pharma companies. Aspen Pharmacare, a South African generic drug manufacturer recently tied up with Hetero Drugs Ltd, a Hyderabad-based company, for technology transfer. The promising areas of co-operation are software products for banking, insurance, telecom, healthcare and e-governance projects.

South Africa’s past was coloured white with First World aspirations. Its trade, ties and thinking aligned well with it. Today, as the country strives for a prosperous black future, it will increasingly lean on emerging countries as reference points.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)