Rediscovery of India

The time is right for India to make dramatic and continuous improvements in health, education and public services to keep pace with the high GDP growth rate

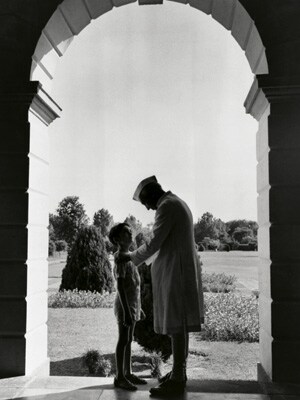

In the late 1950s, Ved Mehta, a blind writer from Oxford, spent a summer in India, a good part of it going around the country with the poet Dom Moraes. One of the high points of his trip was a meeting with the then prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. He had lunch with Nehru and his family (his daughter Indira Gandhi and his ‘two quiet grandsons in their teens’) and a long chat later on. His account of that conversation—published in a book Walking the Indian Streets—is marked by youthful optimism. “I am left feeling that the problems we are facing are of epic proportions, and that men who wish to do their duty must measure up to the heroic possibilities. While heroism seems to be playing out in the West, it is just beginning in the East.”

Mehta was not the only one to see the heroic possibilities those days. India seemed to be a huge canvas and a giant laboratory—coaxing people to think big. It was in this spirit that Milton Friedman, in 1955, wrote a memo at the invitation of the Indian government. “The great untapped resource of technical and scientific knowledge available to India for the taking is the economic equivalent of the untapped continent available to the United States 150 years ago,” he wrote and went on to prescribe policies that would yield a higher growth rate, and to criticise the path India seemed to be taking.

One of the objects of his criticism, Prashant Mahalanobis, whose capital goods investment-led model that India was set to pursue, was no less fired by the same spirit of heroism. A friend of mathematical genius S. Ramanujan at Cambridge, Mahalanobis came back to India in the 1930s to set up the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) and eventually influenced the second five-year plan. J.B.S. Haldane, a British biologist who joined Mahalanobis at ISI, pointing to India’s diversity, called it a model for a possible world organisation. “It may of course break up, but it is a wonderful experiment.” Nehru’s midnight speech—the past is over and it is the future that beckons us now—still echoed then.

It’s tempting to think India today is a different country and the fundamentals are in place. Democracy has taken strong roots. Economic reforms have placed it in a growth path. All you need now is to fine-tune the system, make incremental improvements, and all will be well.

But to do so would be to close our eyes to the problems of epic proportions hiding behind the GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate. The latest Global Hunger Index places India at a lowly 67 out of the 88 worst countries. The Prime Minister recently called abysmal levels of malnutrition and health a national shame. India still has almost 60 percent of its population stuck in an un-remunerative agriculture sector. No surprises then that even by the minimum standards of Rs. 25 a day, we have over 40 percent of the rural population living below the poverty line. Among those living in urban areas and lucky enough to be educated, there is a growing problem of employability.

Worse, the idea of being an Indian is lost on a good number of citizens. The case of Kashmir is well known, thanks to Pakistani involvement. In over a third of districts, armed Naxals are making sure that the country’s attention is turned towards them.

One cannot blame this government for not attempting to solve some of the issues. In the last few years, it passed a right to information act, right to education act, a rural employment guarantee act and more recently it introduced a food security bill.

In this series, perhaps the most debated was the anti-corruption bill. An interesting strand in this debate was whether we need such a far-reaching legislation at all. Wouldn’t tweaking the existing laws solve the problem?

This dilemma is not unique to policymaking. Businesses face it too: Re-engineering vs. Kaizen. Re-engineering refers to fundamental rethinking of a system resulting in dramatic improvements. Kaizen is about small, but continuous, improvements. History shows the best companies do both. They constantly try to become better every day. But once in a while, businesses are hived off, bought, old systems are thrown out and new ones take their place.

The idea behind this exercise is to apply re-engineering to some of the most important areas—health, education, skill development, public services, Centre-state relationship. The timing is appropriate. It would be sad to let go off this moment.

In the book, Ved Mehta quotes his friend Moraes: “Nehru is doing with India, what poets do with words.” In the following pages, our essayists do with words, what we hope our leaders will do with India.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)