Workscape 2.0

With economics sorted out (somewhat), Indians are now turning to fix their ergonomics

Ceiling fan languidly rearranging the stuffy air, tiffin box in a corner, large, shiny, black rotary dial telephone, call bell to summon an orderly to dust the photograph of Mahatma Gandhi. This pretty much sums up the office room of the top Indian executives of about half a century ago. Today’s CEOs work in far swankier surrounds, with state-of-the-art communication facilities, expensive art on the walls, plush carpets and flat panel television screens.

Even so, by international standards, the Indian workplace still has a long way to go. Moving down from the chairman’s suite, you’re far likelier to find uncomfortable, poorly designed, unergonomic office spaces, where movement is severely inhibited, where air-conditioning struggles to keep up or overdoes it, where modern technology is force-fitted to architecture from a different era. And then feudal mind-sets find themselves reflecting in things like office furniture — the lower ranks making do with spondylitis-inducing chairs while the brass recline in spine-supporting splendour — and parking spaces, where the convenience of a few, usually the decision-makers, is more important than the productivity of many.

As the Indian economy grows and opens out to the world, our offices have been evolving. A handful of modern workplaces — the ICICI Bank headquarters in Mumbai or the SAP Labs office in Bangalore — incorporate ground-breaking techniques to make the work environment pleasant and invigorating for the average executive. But they remain exceptions rather than the norm; futuristic offices as a trend are yet to go mainstream.

Here’s the thing. People are used to their offices being better than their homes. And we’re now living in increasing comfort. “People are getting used to plush homes,” says Surendra Hiranandani, co-founder of the Hiranandani group, known for its upscale residential townships. “Naturally, their expectation from workplaces will only get more demanding.”

Indications are that India is about to see a wave of property innovations that will bring workplace architecture to global standards. In some ways, we are where the United States was in the early 20th Century (when the Empire State Building came up) or the United Kingdom in the late 1980s (when the unfashionable old docklands were transformed into today’s swank Canary Wharf business district).

In the commercial capital of Mumbai, where five out of every ten truly rich indians live, and where 40 percent of the country’s tax revenues come from, land is getting increasingly scarce.

Over the last decade-and-a-bit, a marshy piece of land on the banks of the smelly Mithi river was developed and is now the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC). Lined with more glass frontage than any other part of the country, it is well on its way to become the city’s — and therefore the country’s — financial nerve centre.

In the middle of BKC, a building is coming up. It’s not particularly impressive (a mere 12 storeys) on the surface, but it is a preview of what India’s offices are going to look like in the future. When completed, The Capital — that is its modest name — will have five floors of automated unerground parking for 1,000 cars, a three-level “sky lobby,” a 200 sq.ft. video screen on the facade, climate sensitive glass and many other features that promise a completely new experience.

All at a price tag of over Rs 1,610 crore, the highest for any single building so far in the country.

The Capital is not a bolt from the blue. Over the last two years, real estate firms have announced high tech projects in the heart of the city, its former mills area, which promise to change the business landscape. And in unfashionable Wadala, a 100-storey building is being conceived, in what is the first indication that vast docklands on the East of the island city may soon join the mela.

Eleven years ago, when ICICI built its blue-glass tower in BKC, real estate consultants called the building extravagant and outlandish. It was inefficient, they said, because it did not make good use of the available space to cram more people in. Today, its look has been replicated in a number of buildings in the area and ICICI Towers is lost among them.

Times are different today. Corporate groups like the Tata, Birla, Jindal, Essar, airline companies like Jet Airways, have grown several times their size in the last six years. The Jindals have already bought a large piece of land in BKC to construct their future headquarters. Jet Airways too had booked a place but gave it up after his business hit too many bumps. India’s largest company, Reliance Industries, has bought a large swathe of BKC to construct a convention centre; it also owns the garden in front of The Capital. It plans to build an underground parking lot there.

Seen againts this background, The Capital’s timing is important.

The structure is being developed by Mumbai builder Vijay Wadhwa, who has been recently focussing his attention on creating classic buildings with expensive European technology and design elements. It will go on stream in 2012 and house eight to ten large companies. If rules allow, more floors could be added. Wadhwa has already sold 250,000 sq.ft out of seven lakh sq.ft. of planned space and is close to tying up another 300,000 sq.ft. with two banks.

At first look, the building hardly looks impressive. A giant transistor radio-like appearance hides the cool possibilities within. But inside are some key features: Separate entrance for the staff of each large company to ensure privacy, data protection. A German lift-parking system will stack up vehicles over five levels, and there will be a swipecard-controlled retrieval system for cars and a recreation and showering area for drivers. Photochromatic exterior glass will automatically adjust to sunlight just like modern eye glasses.

While high on utility, The Capital just missed out on also becoming iconic. Wadhwa had bought the piece of land in a government auction, at a very high price when the real estate market was at its peak. He started with a more evocative design in mind. He wanted the building to be in the shape of an egg made of steel and glass and he had the designs and final plans done by the famous Hong Kong-based architect James Law. Known for buildings he terms ‘cybertectures,’ Law uses a combination of high technologies, architecture and multimedia experience to create new generation buildings. He has several iconic residential and commercial buildings to his credit in West Asia, Hong Kong, Singapore and China.

But the egg shape suddenly looked unviable with the onset of the financial crisis and the real estate price correction. It wasn’t the most optimal use of space. Wadhwa had to change his plans. Fortunately for him, the government came to his rescue. As a one-time concession, it allowed builders who had bought land at very high prices to build more usage area per unit of land. As the egg-shaped design had still not got approval from authorities, Wadhwa shelved the plan and settled for a more ‘commercially viable’ option.

“I had two options: To create a me-too and fight with the rest of the market or create a premium building that will move on its own strength,” Wadhwa asserts.

Make no mistake, The Capital is not about height. It is dwarfed by existing structures in Mumbai, let alone iconic buildings in America, Europe and South East Asia. It is about how it is going to change the experience for the executive who spends much of his waking hours in the office, for the business visitor often put off by the unhelpful corporate lounges or the thousands of support staff who run such facilities but hardly find a corner to relax. The Capital’s design seems to be sensitive to all such needs. And the time may have come for India to have more such buildings.

Urban Landmarks

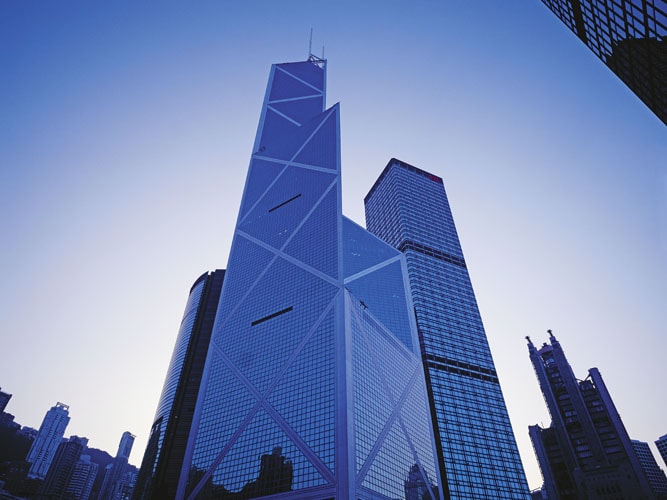

Inaugural year: 1990

Architects: I.M. Pei

Controversy marked the building from the start as the then government of Hong Kong was charged with selling the piece of land on which the tower was built at a cheap price. Bank of China paid $1 billion for the plot, half the price that was paid for a similar sized plot just days ago. The 72 storied building was the tallest in Asia until 1992 and the first building outside the US to break the 1000 feet market. The building also created controversy as it bypassed the convention of consulting with feng shui masters on matters of design prior to construction (they objected to the many edges in the building). When created, the architect wanted to create a structure that would represent the aspirations of the Chinese people yet also symbolise goodwill toward the British Colony.

Inaugural year: April 2004

Architects: Lord Foster and his partner Ken Shuttleworth

The Swiss Re building (popularly known as The Gherkin for its unique design) is located in the heart of London’s financial district. Several constraints from the city building authorities and conservationists saw several architectural plans for the building being modified before the city council passed the radical shape.

The building hosts a bar for tenants and their guests, featuring a 360-degree view of London, on the 40th floor and sports marble stairways.

The building has won several awards, including the Royal Institute of British Architects Stirling Prize in 2005. In early 2007, IVG Immobilien AG and UK investment firm Evans Randall bought the building together for £630 million (approx. $1.26 billion c. 2007).

All images, except the Bank of China building and The Gherkin are an artist’s rendition of The Capital building.

All images, except the Bank of China building and The Gherkin are an artist’s rendition of The Capital building

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)