Walking with Giant Anteaters

Despite their size, these large creatures live camouflaged in the Brazilian grasslands

There is a distinct separation between the routine of everyday existence and the transformative excitement of travel, exemplified by the sense of release as a plane ascends into the sky, signalling the start of a journey.

As the Boeing 747 climbs out of Sydney, setting course for its long trip across the Southern Ocean to South America, I ask Jade, my partner of nearly 30 years, what she is looking forward to most. Several minutes of considered reflection later, she replies: “Giant anteaters. I am looking forward to seeing them again. They are truly weird.”

Native to the grasslands and rainforests of Central and South America, the giant anteater is a large insectivorous mammal, around two metres in length and one metre in height. The elongated snout, extended bushy tail, long claws and distinctive colouration make it instantly recognisable.

We had seen a giant anteater earlier, briefly. It was asleep in some bushes on a cattle property in Venezuela’s Llanos. When they sleep on hot days, these anteaters curl their large tails over their bodies to shade themselves from the sun (known as parasol-ing). Disturbed by the sound of our vehicle, the anteater had run off, offering us only a tantalising glimpse. This time we are hopeful of a closer encounter.

Despite its large size and claws, which are capable of ripping apart rock-hard termite nests, giant anteaters are typically placid, posing little threat if unmolested. They have poor eyesight and hearing, reflected in their small eyes and ears. But their sense of smell is acute, some 40 times more sensitive than that of humans. It is possible to get very close to them, by remaining quiet and downwind.

Image: Corbis

The black-tufted marmosets have hair around their ears, making them look like members of a religious sect

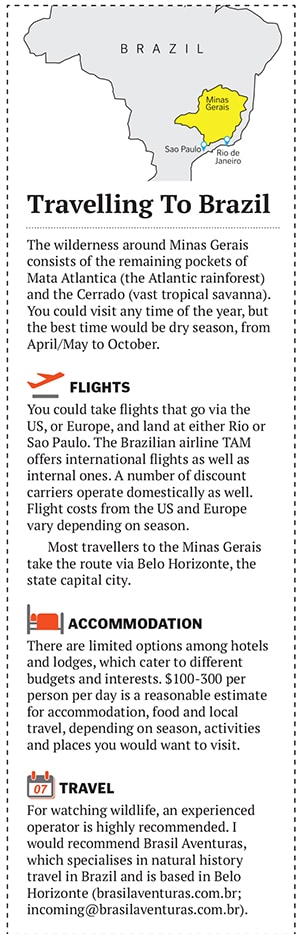

General Mines

Our destination is the unpromisingly named Minas Gerais (meaning General Mines), one of the largest states in Brazil by size and population. The state’s economy, around 10 percent of Brazil’s economic output, is powered by agriculture (milk and coffee), minerals (iron ore) and automakers (the factories of Fiat and Mercedes-Benz). The state also enjoys a curious distinction: Having contributed the largest number of Brazilian presidents, including current incumbent Dilma Rousseff.

Our destinations are the Caratinga, Caraça and Canastra national parks, pockets of remaining wilderness that survive precariously amid Brazil’s rapid economic development.

After a few days spent in enjoying the sybaritic pleasures of Rio de Janeiro, we travel to Belo Horizonte, the capital of Minas Gerais. At the new airport, located a long way and several lengthy traffic jams from Belo, we meet Frederico Costa Taveres, our guide for our 10-day exploration of Minas Gerais’ natural history. He greets us with a jovial: “Call me Fred.”

Fred’s interest in mammals and birdlife began accidentally when he was hired by an artist painting birds for field guides. Years later, his sharp eye and deep knowledge of the creatures of Brazil make him an excellent guide. Fred is relieved that we are not “hard core” birders, interested only in ticking off a lengthy list to the exclusion of everything else. That we don’t take photos is also positive, reducing the pressure to conjure up perfect views and light for demanding shutter-happy tourists. His infectious enthusiasm (the word “fantastico” being integral to his vocabulary) and good humour make him pleasant company.

Supping With Wolves

Caraça is an unusual destination, even for the ardent traveller. Partly converted into a tourism destination, it is a monastery, whose extensive acreage provides a refuge for wildlife amid surrounding farming communities.

The Spartan accommodation targets the ascetic traveller. Service, when we ask for soap and towels, is heavily reliant on divine intervention and prayer.

The forest surrounding the monastery is rich in wildlife. But on our first day there, we see no signs of the black-fronted titi monkeys or the black tufted-eared marmosets that we are looking for.

On the second day, at breakfast, we hear the distinct vocalisations of the titis, endemic to Brazil. Quiet yesterday, the Tanque Grande forest trail brims with life today. Groups of both monkeys are on the edge of the trail, providing good views as they cross the path above our heads.

The titis have orange-brown bodies and a striking black forehead and crown. The smaller marmosets have characteristic black tufts of hair around their ears, making them look like members of a religious sect.

For an hour or so, we enjoy their company as they forage, eat and play near us. But the real attraction at Caraça is a unique opportunity to see maned wolves, the largest canid in South America. We are told that a small local population of the wolves regularly visits the monastery to feed on meat left for them by the monks.

The viewing conditions, however, are not ideal. On one night, we are surrounded by hundreds of primary school children, all seemingly afflicted with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Although wary of staged wildlife events, we know this may be our only opportunity to see the maned wolves, with less than 2,000 left in the wild.

On the two successive nights we are in Caraça, we get very close views of the wolves on the patio of the monastery. The description of “a fox on stilts” does not do them justice. Their elegant gait resembles the cat-walk sashay of a fashion model. The long legs (up to a metre high) are an adaptation for the long grass of South America’s Cerrado (grasslands), enabling them to see, stalk and kill small mammals, usually with a spectacular pounce. As night falls on Caraça, we hear their curious roar-bark.

Our second evening at Caraça brings an unexpected bonus: A hognose skunk, its prominent white stripe setting off the black body. Our excitement contrasts the reaction of other tourists, who fear the skunk’s odorous reputation and the fact that it may keep the wolves away.

Image: Corbis

The muriqui, a woolly spider monkey and the largest New World primate

Monkey Business

Four hours west of Caraça lies the Caratinga Biological Station, part of the Feliciano Miguel Abdala Private Reserve. It is named after the land owner who fought to protect this patch of Atlantic forest, preserving the species unique to this habitat. The Reserve is famed for four species of New World monkeys.

Within minutes of arriving, Roberto, a local guide attached to the Biological Station, takes us to a location where the researchers have seen a group of muriqui, or woolly spider monkey, the largest New World primate. Once widespread, less than 1,000 of them are now left, a result of hunting and habitat destruction.

High in the trees, we spot a large group numbering over 40 individuals, with a number of infants. The monkeys have a greyish brown coat, with long limbs and a long prehensile tail.

As they wake up and begin to move and forage, we follow them through the forest. They move through the treetops, jumping from branch to branch, tree to tree. We witness a mother helping her infant move through the canopy, 30 metres above the ground. She holds two branches, using her body to create a bridge, allowing her young to cross from one tree to another.

We are accompanied by local schoolkids; unlike the group at Caraça, they are quiet and respectful. We share our binoculars and telescopes with them, giving them closer views of the muriqui. We see capuchin and brown howler monkeys as well, enjoying one of our favourite sounds of the forest—that gives howlers their name. The unearthly sound resembles an approaching tsunami and can travel up to five kilometres through dense forest.

But to catch a glimpse of the rare buffy-headed marmoset, we know we will need luck on our side. Roberto tells us that a few days ago their calls were heard briefly in one part of the forest. We make our way there in the late afternoon and wait, listening and scanning the forest. Jade suddenly spots them. A group of five or six individuals are in the trees about 500 metres from us, and we are able to get excellent views through the telescope.

The tiny species resemble gremlins. Their appearance is dominated by the eponymous orange-yellow fur on their heads, cheeks and hair tufts around their ears that contrast sharply with their black and grey body. Like all marmosets, they have claws instead of nails on all digits, enabling them to cling to trees with ease. We watch them gouge holes in the trees to encourage the flow of sap, which they return to drink a day or so later.

Then they are gone. And the next day, there is no sign of them.

Digital Birding

South America is for birds what Africa is for mammals. In 10 days, we see well over 160 species—ostrich-like rheas, different species of tinamous, rails, ibis, antbirds, manakins, toucans, hummingbirds, trogons, puffbirds, woodcreepers, ovenbirds, tanagers and an extraordinary variety of tyrants, New World flycatchers.

We have fantastic views of blue-winged macaws, Toco toucans and black-necked aracaris (a smaller species of toucan); we have a glimpse of a red-ruffed fruitcrow as it flies low over our heads; we watch a large lineated woodpecker excavating a nest; we watch several Blue Manakin males ‘dancing’ for a female.

Our favourite birds of prey—vultures, hawks, falcons—are everywhere. Fred tells us his young daughter Cecilia wants to know what Roadside Hawks were called before there were roads. We don’t have an answer.

To augment our sight and hearing, Fred deploys technology: A digital MP3 player with over 600 different bird calls. If the bird is in the vicinity then the call may make it investigate, bringing it into view. There are ethical issues involved here. It is cheating. It may stress the bird. Fred tries to minimise the impact by restricting the use of the taped calls.

But its effect can be remarkable. A Brasília Tapaculo, a tiny insectivore that generally stays in dense vegetation and is therefore difficult to see, responds to the taped calls and is drawn out of the thick undergrowth, to the point where it literally hops past my boots.

Trailing the Giants

Canastra is a 2,000-sq-km national park, with two distinct sections. Lower Canastra consists of rivers, streams and gallery forests, with excellent birdlife. We are fortunate to see several critically endangered Brazilian mergansers through the telescope on the Sao Francisco River. There are now only 400 mergansers left in the world, mainly due to the deteriorating quality of water in the rivers and streams.

Upper Canastra is a box-like plateau rising several hundred metres above the surrounding countryside, accessible only by a steep, twisting unsurfaced road. The plateau itself is covered in rolling grasslands, with a fine, red, pervasive dust during the dry season. The landscape of the Cerrado, the Brazilian savanna, contrasts the verdant forests usually associated with Brazil.

We spend long days scanning the grasslands from any vantage point for giant anteaters, a difficult task given the flat landscape. Fred assures us that when we see an anteater very close we will see why they are so hard to spot.

On our first afternoon there, Fred “thinks” he might have spotted one. We get in the car and drive about a kilometre to where he thinks he saw it. We make our way on foot through tall grass. After a frustrating half hour, we find nothing. We make our way back to the car, drive back to the vantage point and look again. Fred thinks we went to the wrong spot, easy in a landscape without distinctive markers. We double back and start searching through the grass, taking care to be as quiet as possible and staying downwind of where the anteater might be.

Suddenly, they materialised mysteriously. To our surprise, there are two giant anteaters only metres from us.

Up close, it is obvious why they are so difficult to spot. The grey-and-white body and the brown tail blend almost perfectly into the grasslands. The coat hair and stiff mane have the texture of dried grass, completing the camouflage and making them near invisible. We now understand what Fred was searching for—a slow-moving vague dark line, the blackish stripe along the anteater’s back, occasionally visible in the tall dry grass. Despite the fact that we are now within a metre of them, they appear unconcerned. The proximity allows us to see every detail vividly.

Image: Corbis

A hognose skunk, with its prominent white stripe setting off the black body, bears an odorous reputation

Their necks are extremely thick, larger than the animal’s head. The anteaters walk slowly on their knuckles, keeping their elongated claws out of the way. They are feeding, using their 60 centimetre tongues—that moves in and out of the tube-like mouth—to lap up termites and insects. The insects, trapped in the thick, sticky saliva are swallowed and crushed against the palate. In a unique adaptation, anteaters do not produce their own stomach acid, but use the formic acid of their prey for digestion.

We walk with the two for around an hour until they disappear into the grass.

Over the next few days, we see several more anteaters. We are lucky enough to see a mother with a baby, characteristically being carried on her back.

The strange languid hour, walking with the giant anteaters leave Jade and me speechless. Fred has experienced this many times before, but his pleasure in sharing the wonder and joy of the occasion with us is clearly evident. The moment is, as he would say, “Fantastico!”

© 2014 Satyajit Das. All rights reserved. Das is a former banker and author of Traders, Guns & Money and Extreme Money. He is also the co-author with Jade Novakovic of In Search of the Pangolin: The Accidental Eco-Tourist.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)