The secret lives of young achievers

The young have always been successful. But has it become easier or more difficult for them over the years?

Priyanka Raja and Prateek quit their jobs to start Experimenter in Kolkata

Priyanka Raja and Prateek quit their jobs to start Experimenter in KolkataYouth is not always wasted upon the young. More so now, in contemporary times, when the number of youngsters achieving greatness—and not merely being born into it, or having it thrust upon them—seems to be higher than before. It would give the appearance that it has never been easier to have access to opportunity and the means to change ambitions into reality.

As our 30 Under 30 lists, now in the fifth year, have amply shown, youngsters are no longer held back by factors that shackled youngsters in previous generations. They no longer have to be born into a rich family to get capital for their fledgling enterprise, they don’t need to ask relatives and friends coming in from foreign countries to bring them a covetable guitar or amplifier, and they don’t need to live in big cities to get noticed. They don’t even need to go through the motions of qualifying as a doctor, or engineer, or a lawyer for their parents to not be disappointed in them. And, of course, there’s the internet.

Times, truly, have changed. But is it all for the better? The jury, it seems, is out on that. For increased access, capital and opportunity mean the same advantages are available to a large number of people. This ever-burgeoning talent pool means it is that much more difficult to outshine everyone else and make a mark for yourself.

Priyanka Raja, 37, who, along with husband Prateek, 38, started Experimenter, an art gallery, in Kolkata in 2009, says youngsters today feel they can find success wherever they are. “Thirty or 40 years ago, people thought they could find success in certain places; either the big cities, or in other countries,” she says. “Today, the 20-to-40-year-olds feel ‘location-free’. In our case, when we decided to become gallerists, we had to think of where we would be able to find the audience, not the market.” This led to both of them giving up their corporate jobs and heading to Kolkata—where they both are from—to open Experimenter.

This is a sentiment echoed by Ayaz Memon, 66, sports writer and author. “The national footprint of every sport has increased. Earlier, cricketers, for example, would come only from the metros,” he says. “Today, good cricketers are coming from tier 2 and tier 3 cities.” Former India captain MS Dhoni, a native of Ranchi in Jharkhand, is perhaps the best example of this trend.

The base of the pyramid, Memon adds, has grown enormously for certain sports, such as cricket. While it has also grown for lawn tennis, football and hockey, the lack of adequate training infrastructure—such as artificial turfs—means they are still not as big as they can be.

Memon feels that the bigger the base of the pyramid, the better the quality of those who make it to the top. “It’s a filtration process,” he explains.

Aneeth Arora (overleaf), founder, Péro, says one must believe in their abilities

Aneeth Arora (overleaf), founder, Péro, says one must believe in their abilitiesImage: Madhu Kapparth

But climbing up that pyramid is hardly an enviable task. Aneeth Arora, founder of design label Péro, says there are two sides to the coin. “There is a lot more opportunity today,” says the 36-year-old fashion designer, whose clothes are sold in 250 shops across 30 countries. “Today there are far more design categories for clothes. Earlier, there were just a few, such as bridal and casual. But today there are also too many fashion graduates being added to the market every year. Very few chose to become fashion designers earlier.”

To give an idea of the number of players in just one sector—technology—it would be apt to highlight a November 2017 Nasscom report that says India added 1,000 startups in the last year, taking the total number of technology startups in the country to 5,200. Twenty percent of them emerged from tier 2 and tier 3 cities.

But the argument of a growing national footprint may not be true for all pursuits. Sunil Shanbag, 61, theatre director, screenwriter and documentary maker, says, “The movement of talent and resources to the urban centres has increased, so large parts of the country are becoming hard to work in. Theatre festivals in smaller cities feature work from Mumbai and Delhi, and there is hardly any representation of local talent. All this should be a matter of concern.”

But Shanbag agrees that there are more opportunities, and consequently greater competition, today than before. “There are many more opportunities for a talented person today, and perhaps because of this it’s that much harder to stand out, unless you are in the mainstream which is backed by a huge media machine which is constantly looking for new material.”

And talent alone may not be enough anymore to excel. Shanbag says the external factors that play a role in achieving success “have remained more or less the same. People who understand how to play the system always seem to get ahead quicker than those who don’t. The difference may be that while playing the system was frowned upon [earlier], now it’s an enviable virtue”.

Anjan Chatterjee and Yash Bhanage say the difficulty in setting up a restaurant is still the same

Anjan Chatterjee and Yash Bhanage say the difficulty in setting up a restaurant is still the same Images: Anjan Chatterjee: Joshua Navalkar; Yash Bhanage: Tejal Pandey

Yash Bhanage, 31, co-founder of Bombay Canteen and O Pedro restaurants, feels that a lot of youngsters today are ambitious, but ignorant to the realities of starting an enterprise. “Everyone wants to start the next Facebook or Instagram, without being aware of the difficulties and the hard work,” he says.

“There are those who want to open a chain of restaurants because some startup has got a large amount of venture capital funding, and they believe they too can get something similar,” adds Bhanage. “But what they don’t know, and don’t understand, is that funding does not mean the founder is getting the money in is his pocket. There are lots of strings that come attached with the funds, because the venture capitalists want a certain kind of growth path. Youngsters get distracted by the valuations of companies, and fail to see reality.”

When asked what he feels about food entrepreneurs who have succeeded years before him, he says, “I have spoken to people like Anjan Chatterjee [founder, Speciality Restaurants], and we discuss that gone are the days when you could just serve good food, and expect people to come in. Today’s diners expect so much more than just food.”

Chatterjee himself says changing customer behavior means that the environment of restaurants needs to be refreshed because diners come in for the experience. “It’s a business of happiness,” he says. “ You can’t have grumpy employees. And something like music adds so much energy.”

Comparing his own experience of starting out to that of young restaurateurs today, Chatterjee, who began his career in hospitality with an outlet of Only Fish in Mumbai, remembers, “When we started in 1991-92, I had gone to a bank to get a loan of ₹2 lakh. But they didn’t take me seriously,

because they did not believe this to be a viable industry. Today, everybody [investors] is backing food, and it is much easier to get funding. There is also a technological advantage, with platforms such as Swiggy and Zomato, and so many avenues to maximise revenue streams.”

What seems to have remained the same is the difficulty of setting up a restaurant business. “Despite the fact that we employ a large number of people, the government has not made things easier. There is a single-window clearance in other countries, which is very strict, but efficient. Even where GST is concerned, restaurants have to pay a high input credit,” says Chatterjee. Bhanage agrees that despite the talk about digital revolution, rules and regulations continue to hobble new restaurateurs.

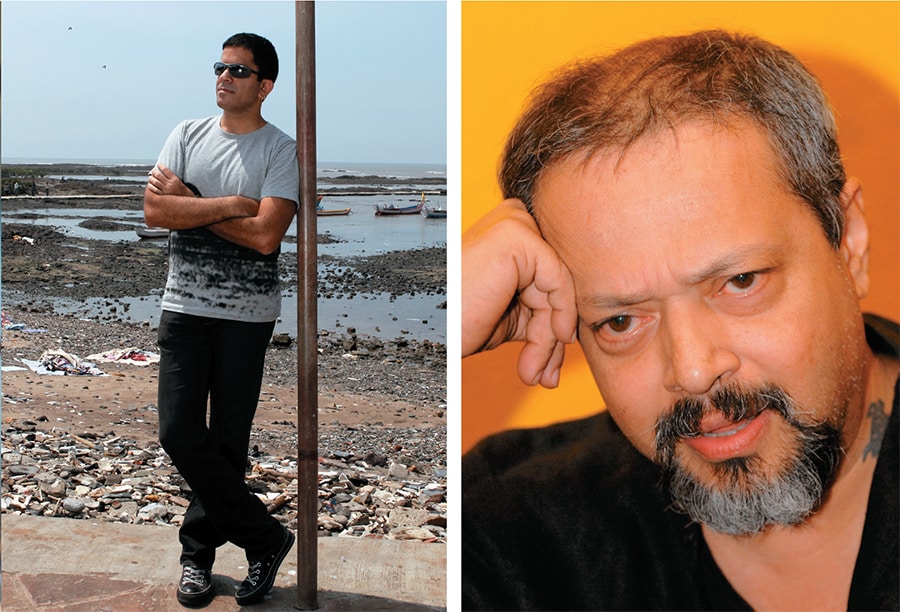

Uday Benegal (left) and Sunil Shanbag are of the opinion that there are multiple opportunities to succeed today

Uday Benegal (left) and Sunil Shanbag are of the opinion that there are multiple opportunities to succeed todayImage: Sunil Shanbag, Uday Benegal: Getty Images

And while the strings and pitfalls of opening a new business are often not talked or written about, access to information, in itself, is something that should be handled with care, says Bhanage. “While addressing our team, we always say that it is up to us to read what is there [on the internet] and use it to our advantage,” he says.

Arora, too, handles the internet with care: Neither does Péro have an online store, nor does she put up her designs on an online platform. “There is no foolproof way in which you can guard against your designs getting copied,” she says. She does concede, though, that social media and the digital medium have played an important role in her success: “It has its advantages. Like you can quickly gauge audience reaction.”

Singer, songwriter Uday Benegal, 50, feels that youngsters today are an immensely talented lot, who have more opportunities and access than those in the past did. Making a comparison between ‘then and now’, Benegal talks about how difficult and expensive it was for them to procure the musical instruments and equipment they needed for their performances, and the “innovative” ways in which they would source them. “Today, you can easily get the best guitars in India,” he says.

“We were headstrong and lucky,” he says about the 1980s, when he started out as lead singer and principal songwriter of Indus Creed, one of India’s pioneering rock bands. “Thirty years ago, there was no process, no marketing, and no promotions. We were simply playing gigs at college festivals. Then came satellite television, and MTV, which pumped things up, and we got more exposure.” What has also changed, he adds, is how people listen to music. “There was just one [music] channel [MTV], and everyone tuned into it. Today, there’s no one channel, and no one medium. People are searching for what they want to listen to.”

While he agrees that both the talent pool and competition has increased, what he thinks has changed for the better is the mindset of parents. “There is far more open-mindedness among parents today. Consequently, people are in professions that we could not have imagined earlier,” he says.

The music industry has a plethora of career options in areas such as production and management, which means enthusiasts have a greater chance of getting out of the rut of conventional careers.

Echoing his thoughts, Raja says that in the Indian context, “family name” has been very important. This meant that youngsters wasted a lot of time in building one career (one that their parents wanted them to), and then building a second (one that they themselves wanted to). “The current generation of youngsters does not feel the necessity to have a conventional career. Children don’t waste time doing what they are told to do; they do what they want to do,” she says.

Highlighting this approach, Bhanage says of the 140 employees that his restaurants have, about 40 percent have made a career change to work in the hospitality sector. “Food is the new music,” he says. “It is also true that the entry barriers to this industry can be relatively low. So, we do have home cooks who have joined us in the kitchen. We take them because they already have a basic understanding of taste and flavours”

Memon adds that the openness to these opportunities is because it is now possible to make a livelihood out of them. “This awareness has come about in the last 10 years or so. A sport like cricket can bring you phenomenal rewards and international fame. But people have also realised that you don’t always have to be a winner [in sport], because there is a huge industry around it now that can provide opportunities of various kinds, in training, sports medicine, writing and commenting.”

Shanbag acknowledges the increased opportunity for theatre actors to earn a living through their trade. “The easy movement between different media such as film, television, and theatre makes it possible for younger people to survive and work,” he says.

But despite all the difference in opinions, everyone agrees that there is no alternative to hard work. “Genuine achievement always needs the same amount of commitment, hard work, and supreme focus. That hasn’t changed,” says Shanbag. Arora agrees: “There are a lot of people who will tell you that it won’t work… But you just have to believe in yourself.”

Some things never change with time. No matter how much time itself changes.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X