Switzerland declares war on the Apple Watch

How TAG Heuer, Breitling and other luxury brands are changing the face of the smartwatch industry

In 1982, after taking a licking from Japanese competitors that had championed quartz batteries, the Swiss watch industry was facing an existential crisis. But rather than seeing the mechanical movement as a weakness, Jean-Claude Biver, 65, who had recently purchased the defunct Blancpain brand, boldly declared that this artful anachronism represented the industry’s future. “Since 1735, there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch,” Biver’s new slogan declared. “And there never will be.” A decade later, he backed up his words with results and sold Blancpain to the Swatch Group for $43 million.

Today, the Swiss watch industry is again robust—in 2013, there were more than $20 billion in exports—but the advent of the smartwatch and the release of the Apple Watch have pessimists once again wondering if time is running out on tradition.

So this March, at Baselworld (the watch industry’s annual Super Bowl), Biver—now president of the LVMH Group’s watch division, which includes TAG Heuer and Hublot—made another bold statement: “We cannot ignore the trend of the smartwatch.” But this was no capitulation; rather, it was a rallying cry for the Swiss watch industry’s counter-offensive against the smartwatch’s incursion into its territory.

The best way to combat that, Biver argued, was to be smarter. On the opening day of Baselworld, he launched the first salvo with a press conference announcing a groundbreaking new partnership between TAG Heuer, Google and Intel. The result will be a Swiss version of the smartwatch, an Android Wear timepiece powered by Intel technology. Although more information on what the watch will actually look like and what its functions may be (and what, of course, it will cost) won’t be revealed until October, Biver believes the relationship has already been productive. “We enjoyed working with both Intel and Google and could also learn from their culture as much as they could learn from our culture,” he tells Forbes, “as they are more technology-oriented. We are, of course, much more high-end or luxury-orientated.”

Interestingly, it was Guy Sémon, TAG Heuer’s general manager and director of R&D, who initiated the brand’s early adoption of wearable technology. While Swiss watchmakers are often perceived to be staid guardians of the industry’s centuries-old traditions, Biver credits Sémon for pushing TAG “to enter this new technology—not with our traditional knowledge but through the best possible partnership with the giants of Silicon Valley.”

And TAG Heuer is not alone in this mission. At Baselworld, Breitling presented a concept piece that puts the smartphone in service of its B55 Connected watch; while the two tools are complementary, each half of the pair performs its intended task. The result is a COSC-certified chronometer pilot’s watch with features—including time setting, time-zone adjustment and alarm setting—that are accessible via the phone. Similarly, the B55 Connected can upload measurements from the chronograph (such as readings from the electronic tachometer) to the phone for simplified storage and data transfer.

For Breitling’s CEO, Jean-Paul Girardin, the phone was a natural boon to improving functionality. The brand will launch a model based on the B55 Connected concept at the end of the year, but Girardin notes that the “next steps will be dictated by the actual needs of our users and the attractiveness of new technologies. We do not aim to produce connected instruments just for the sake of following a trend.”

Two other brands—Frédérique Constant and Alpina—announced the Swiss Horological Smartwatch, which links Switzerland to Silicon Valley. These timepieces track motion activity and sleep and even know which time zone the wearer is in—but the dials are comfortingly analog, not digital.

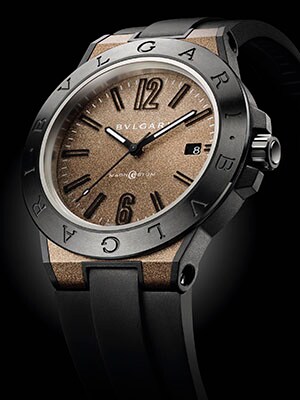

Meanwhile, Jean-Christophe Babin, CEO of Bvlgari, says his brand’s new concept piece is “not to be confused with a smartwatch.” The Diagono Magnesium is “first and foremost a manufactured mechanical luxury Swiss watch”—it just happens to contain an NFC microchip that can connect with a smartphone to lock or unlock an ultrasecure cloud app. Bvlgari developed what it cheekily describes as “an intelligent watch” with Swiss information-security firm WISeKey, so the wearer of the Diagono Magnesium can access and protect personal information, all via a purely mechanical watch that acts as an encrypted key to data storage.

Having learnt the lessons of the Great Quartz Crisis, these Swiss brands have carefully considered how wearable technology can be made to bolster their mechanical know-how rather than to simply create Apple flavoured smartwatches. Some change is inevitable, particularly as younger customers gain buying power—they’re getting used to the idea of a watch featuring some sort of connectivity—but Biver insists that TAG Heuer will never give up its DNA as a luxury brand. Indeed, just as in 1982, the industry’s éminence grise still views the mechanical watch as the future—and for good reason. “Because smartwatches are somehow due to become obsolete—contrary to the traditional mechanical watch of our ranges, which are ‘eternal’,” Biver says with confidence. “Yes, in 100 or in 1,000 years, a traditional mechanical watch will still be repairable and will still work!”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)