Sniffing Out Fake, Expensive Wines

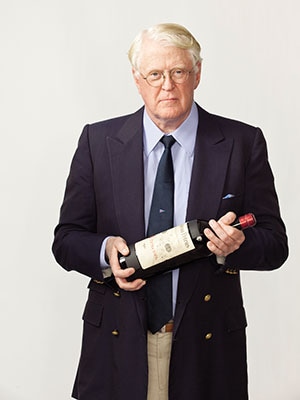

Michael Egan helped solve a multimillion-dollar wine fraud mystery last winter involving billionaire Bill Koch. Now the Wine Detective is sniffing out new counterfeit cases

Crime Scene: A warehouse in Boston. Investigator: Michael Egan, investing fraud in Bordeaux. Temperature: Carefully climate-controlled to a comfortable 55 degrees Farenheit.

The Boston affair was the first high-profle assignment for Michael Egan—dubbed ‘The Wine Detective’ by the New York tabloids when, last December, he helped the FBI break the US’ biggest wine counterfeiting case—and it was a doozy. Tech entrepreneur Russell Frye of Frye Computer Systems had put a portion of his collection up for sale through Sotheby’s in New York in 2006. Billed as ‘The Magnificent Cellar of Russell H Frye’, it rang up $7.8 million, at that time the second-highest total ever for a Sotheby’s wine auction. From Frye’s point of view there was just one massive, bloated fly in the decanter: The estimated $3 million of his other wines Sotheby’s had shied away from.

The bottles that greeted Egan in Frye’s Boston storage facility were beyond trophies. The assemblage included, among other extreme rarities, an 1811 Château Lafte, three bottles of 1847 Château d’Yquem and two magnums of 1921 Château Pétrus. Though he wasn’t told which wines Sotheby’s had refused, Egan rather quickly realised that Frye had a big problem: All of those bottles, and many others purchased from the same source, were fakes.

“They just didn’t look right,” Egan remembers now. And he would know. By the time he launched Bordeaux-based Michael Egan Fine Wine Expert in 2005, the British-born Egan had already put in 24 years at Sotheby’s in London, rising to become a director of the wine department and responsible for rounding up bottles for sale from the Continent. “I was travelling around France, Belgium, Germany and Holland looking at these magnificent family cellars that hadn’t been moved since the 1920s or even earlier,” he says. “It was a great way to see how the patina of age would affect a label over time and what real bottles would feel like and look like.”

Not so much like Frye’s bottles, unfortunately. One immediate red flag: Those magnums of 1921 Pétrus. Egan had come across similar bottles before—and refused them—at Sotheby’s; they had become something of a calling card for the notorious German bon vivant and alleged wine counterfeiter Hardy Rodenstock, who was then being sued in New York. One of Rodenstock’s famous 1921 Pétrus magnums had scored a perfect 100 from the world’s leading wine critic, Robert Parker. But for Egan the wines presented a wee problem: Pétrus didn’t bottle any magnums in 1921. And even if some of its winemerchant customers who bought the wine in barrel had actually filled magnums—and there was no record of that, either—where were all these bottles suddenly coming from?

Egan soon began pulling suspect wines from Frye’s collection and breaking them down by component parts. Some of the labels, he realised, were photocopies that had been distressed—as he puts it, “scuffed in a weird way you wouldn’t see in normal cellaring”. Though the photocopies were expertly done, under his jeweller’s loupe the letters were revealed as pixilated, as from a laser printer. By the time he was done, Egan had identified 30 very expensive fake wines in Frye’s collection.

There are no even vaguely reliable numbers compiled on the value of bogus fine and rare wines that change hands every year (as opposed to the industrial-scale counterfeit bottling of more commonplace wines said to take place in the Far East). Egan’s ballpark estimate is around $100 million. But most of them go undetected, or unprosecuted, partly because, as Russell Frye discovered, “it takes very deep pockets to pursue someone who is selling fake products”. (For that reason Frye ended up settling out of court with the vendor who sold him the ersatz bottles.)

Unfortunately for several big-time wine counterfeiters and the auction houses and retailers that sold their bottles, that deep-pocketed someone arrived on the wine scene: Billionaire William Koch. Koch’s estimate of the size of the counterfeiting market tops Egan’s (“My out-of-the-air estimate,” he says, “is that several hundred million dollars’ worth of fake wine is being sold every year”), which is bad enough in the abstract, but it came home to him personally.

“I bought a lot of fake wine at auction—that’s where I got most of it—but I’ve even bought fake wine at charity auctions! I’ve been given fake wine as a present.”

This rubbed Koch the wrong way. Very wrong: He has now spent, by his estimate, more than $30 million pursuing wine fraudsters. As he says, “It just bugged me that there was this code of silence. The auction houses and the resellers don’t want to know it’s fake because they are making a gross margin, and then when the collectors get it they don’t want anyone to know they have fake wine because it devalues their cellar—they want to dump it, get rid of it.”

When he began to have doubts about a large consignment of dazzling rare wines bought through Zachy’s in New York, Koch turned to Egan to break “the code”. And the Wine Detective went to work: “I told him, sorry, but all the wines you’ve shown me are fake.”

There were bottles with wrong corks—a château name printed in the wrong direction—and doctored labels (a glue expert would later determine that some had been attached with Elmer’s). Remembers Koch, “Michael used his superb access to the châteaux to get harvest records, which were very useful. [For example] I had bought seven or eight magnums of Château LaFleur 1947 , and it turned out there were only five ever bottled!”

Looking on in the Cape Cod courtroom were spectators watching Egan’s testimony with uncommon interest: Agents from the FBI and lawyers from the Southern District of New York’s US Attorney’s office. They soon contacted Egan and put him to work on a made-for-the-tabloids counterfeiting case.

In what appears in retrospect an impossible-to-miss echo of the Hardy Rodenstock scandal in Germany, a man with a hazy, unverifiable past—in this case an Asian expat named Rudy Kurniawan—burst onto the scene with a bottomless trove of wines no one even knew still existed. A charmer with an authentically impressive palate, Kurniawan, like Rodenstock, established himself by throwing astounding, bacchanalian tastings at his own expense. And once again the wine establishment—Robert Parker, Burghound’s Allen Meadows and many others—joined in the chorus of praise.

Kurniawan had pulled off some very public coups—including a $25 million auction sale—and perhaps untraceable numbers of private sales to collectors by the time the FBI raided his Los Angeles home in 2012. The raid netted, among other smoking guns, 20,000 fake wine labels and a cache of empty top-end wine bottles that Kurniawan had bought from sommelier friends, some of them marked right on the glass with the formula he would blend in them to fabricate the original wine.

A counterfeit and a genuine bottle of 1961 Pétrus

As Egan quickly realised, the man was a student of the art: “This was a very sophisticated operation. He had actually scanned the original importer’s back labels from, say, the 1950s and 1960s, and had those printed professionally.” But even the cleverest criminals trip themselves up. Egan’s sleuthing discovered, for example, that the label on a bottle of 1929 Roumier Bonnes-Mares bore an all but imperceptible watermark ‘Concord’) that he traced to an Indonesian printing company established in 1983.

At the trial last December that ultimately convicted Kurniawan of fraud, Egan was able to draw on his years of experience to verify that, on various assignments, he had personally examined and determined to be fake 1,077 bottles of wine attributable to Kurniawan. The 267 bottles the FBI had seized from his home or rounded up from other sources—all of them fakes, Egan testified—were only the tip of an otherwise invisible iceberg. As Egan puts it, in regard to the market in general: “There is a lot of fake wine about, and a lot that has yet to come to light.”

Which means a full caseload for the Wine Detective, who has clients—collectors, wine merchants, law enforcement, auction houses, restaurants, casinos, hotels and law firms—from France to Macau and Singapore. Recently Egan helped confirm a Danish wine magazine’s suspicions that two high-flying wine impresarios were actually refilling the same ultra-expensive bottles for the clients of their exclusive White Club tastings. “The beauty of my job,” he says, “is that I do not know what’s coming next. I can be looking at stocks belonging to merchants or auctioneers, as with all the litigation concerning fake wine they now must do their due diligence. I can be checking a few bottles that people bring to me, or I can be looking at wines on behalf of a potential buyer.”

This summer, as Egan awaits the unfolding of a major US case—and potential trial—involving counterfeit Burgundy and Bordeaux, he will be doing authentication work for a client in Asia, checking bottles in Europe and wrapping up his inspection of an American cellar.

Meanwhile Russell Frye has done his part to combat wine fraud, too, establishing a web-based clearinghouse for information about fraud called WineAuthentication.com.

But as he says, “We are happy to answer questions and give opinions. But if someone really needs an evaluation, I will send them to Michael Egan and tell them to pay his fees.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)