Sanjeev Kapoor: The culinary czar

Chef Sanjeev Kapoor's foray into the US, with three new restaurants, is yet another ingredient on his platter of success

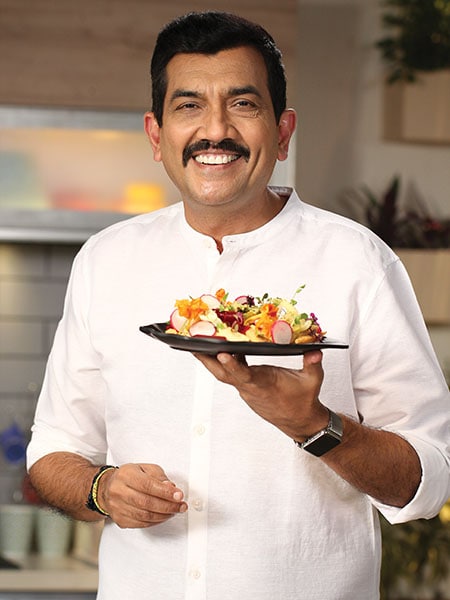

Sometime in the early 1990s, women across urban Indian households began to find themselves glued to their newly liberated television screens, waiting for the smiling face of a man they were beginning to trust. Once a week, he would appear on screen at the designated time, without fail, grabbing attention like no other before him.

But instead of serenading heroines and fighting goons, he would be imparting invaluable insights into the making of creamy swirls atop chocolate icings of soft sponge cakes, or spilling the secrets of making the perfect malai kofta. His star-struck audience, pen and paper in hand, rapidly scribbled and hung on to every word he uttered during the hour-long programme.

Sanjeev Kapoor was India’s new matinee idol.

That Kapoor, now 54, quit his job as a chef in 1992, and opted instead for the uncharted territory of cookery shows on television—this was long before food became the sexiest thing on TV, with international names such as Gordon Ramsay and Nigella Lawson, and MasterChef still more than a decade away—was a sign of things to come. For him, and for the empire that he has gone on to establish.

But instead of serenading heroines and fighting goons, he would be imparting invaluable insights into the making of creamy swirls atop chocolate icings of soft sponge cakes, or spilling the secrets of making the perfect malai kofta. His star-struck audience, pen and paper in hand, rapidly scribbled and hung on to every word he uttered during the hour-long programme.

Sanjeev Kapoor was India’s new matinee idol.

That Kapoor, now 54, quit his job as a chef in 1992, and opted instead for the uncharted territory of cookery shows on television—this was long before food became the sexiest thing on TV, with international names such as Gordon Ramsay and Nigella Lawson, and MasterChef still more than a decade away—was a sign of things to come. For him, and for the empire that he has gone on to establish.

Now, he is expanding his empire yet again, and to new foreign shores—the United States (US). Long considered to be in the realm of neighbourhood restaurants, takeaways and budget buffets, Indian food in the US began to get a posh patina with the arrival of restaurants such as Junoon, Indian Accent and Tulsi in New York, Rasika in Washington DC, and Rasa in San Francisco. Entering this arena is Kapoor, who has established 59 restaurants in India and the Middle East so far (with seven more in the pipeline). “In the Middle East, we are almost everywhere where we thought that restaurants with Indian food would be justified. One of the last places of significance was Saudi Arabia, so we are opening a restaurant there are as well,” Kapoor says. “In terms of growth, we realised that we would want to open in places where the Indian diaspora is significant. So those markets are defined: Europe, primarily the UK, and North America. Other places are there—Australia, New Zealand, Africa—but they are smaller markets.”

The North American market is bigger, in terms of size and opportunity. And although the UK, especially London, presents another big opportunity, “we did not have a product among our existing brands that I want to do there. So we chose North America, where we first tested with three restaurants in Canada and then, another three in the US, in California—Buena Park and Santa Clara—and Atlanta.”

The North American market is bigger, in terms of size and opportunity. And although the UK, especially London, presents another big opportunity, “we did not have a product among our existing brands that I want to do there. So we chose North America, where we first tested with three restaurants in Canada and then, another three in the US, in California—Buena Park and Santa Clara—and Atlanta.”

As part of his strategy, he is eyeing the East Coast of the country as well. While the California and Atlanta restaurants are The Yellow Chilli brand, the ones in Canada are the Khazana brand. “For California, we looked at casual dining, something with good food but not expensive, with a price point of $25-30 per person. That is why we thought of The Yellow Chilli,” he explains, adding “we are looking at other brands also.”

Although he will not put a number to it, Kapoor is clear about his next step in the US. “We have defined the market, what the opportunity is. But in terms of actual numbers, we want to look at the first year, we would like to evaluate the performance,” he says. And London definitely remains on his mind: “We are keen on the UK market, and I am working on a new concept for it. As soon as I get something exciting, we will go for it.”

Although he will not put a number to it, Kapoor is clear about his next step in the US. “We have defined the market, what the opportunity is. But in terms of actual numbers, we want to look at the first year, we would like to evaluate the performance,” he says. And London definitely remains on his mind: “We are keen on the UK market, and I am working on a new concept for it. As soon as I get something exciting, we will go for it.”

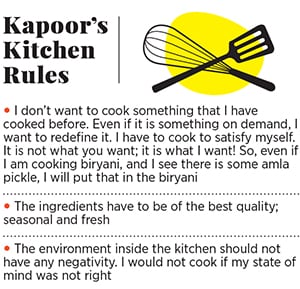

Since starting the cookery show, Khana Khazana, on Zee in 1992 (it ran for the next 18 years), Kapoor has set up businesses that include a chain of restaurants in India and the Middle East, TV channel FoodFood, a range of premium cookware under the brand WonderChef, a range of pickles, blended spices, gourmet chutneys and ready-to-eat mixes under the brand name Khana Khazana, along with publishing innumerable cookbooks. He has, quite literally, a finger in every pie.

But every pie, he says, is ultimately about food. “[My businesses] are not really diverse because everything has food at its core. Only the media of reach are different,” he explains. “In terms of managing [all the different verticals], I realised that the best way to manage is to not manage them at all, and find people or partners who would do that for you. I create joint ventures. I come with the limited knowledge that I have, and keep focusing on that. That’s what I bring to the table.”

As a businessman, Kapoor has taken steps, first measured and then rapid strides, in the right directions at the right times. So, if he quit his job as the executive chef of Mumbai’s Centaur Hotel in the early 1990s to host a television cookery show, it was at a time when India was waking up to the possibilities of a liberalised economy and satellite television. Riding on the phenomenal viewership of Khana Khazana—it would become the longest-running television show in Asia, with more than 500 million viewers—he launched his first restaurant, Khazana, in Dubai in 1998. In the following 10 years, he opened 18 restaurants—in India and the Middle East, regions with a strong market for his brand of Indian cuisine—but in the next nine years, that number bounded to 70.

While Khana Khazana drew to a close after its phenomenal run, Kapoor continued his association with the world of television by launching his 24-hour food channel FoodFood in 2011, as a joint venture between Malaysia-based Astro Overseas Limited and Mogae Consultants. (In 2016, Kapoor sold a majority stake in the channel to Discovery Communications, while remaining its brand ambassador.)

But every pie, he says, is ultimately about food. “[My businesses] are not really diverse because everything has food at its core. Only the media of reach are different,” he explains. “In terms of managing [all the different verticals], I realised that the best way to manage is to not manage them at all, and find people or partners who would do that for you. I create joint ventures. I come with the limited knowledge that I have, and keep focusing on that. That’s what I bring to the table.”

As a businessman, Kapoor has taken steps, first measured and then rapid strides, in the right directions at the right times. So, if he quit his job as the executive chef of Mumbai’s Centaur Hotel in the early 1990s to host a television cookery show, it was at a time when India was waking up to the possibilities of a liberalised economy and satellite television. Riding on the phenomenal viewership of Khana Khazana—it would become the longest-running television show in Asia, with more than 500 million viewers—he launched his first restaurant, Khazana, in Dubai in 1998. In the following 10 years, he opened 18 restaurants—in India and the Middle East, regions with a strong market for his brand of Indian cuisine—but in the next nine years, that number bounded to 70.

While Khana Khazana drew to a close after its phenomenal run, Kapoor continued his association with the world of television by launching his 24-hour food channel FoodFood in 2011, as a joint venture between Malaysia-based Astro Overseas Limited and Mogae Consultants. (In 2016, Kapoor sold a majority stake in the channel to Discovery Communications, while remaining its brand ambassador.)

.jpg) The Yellow Chilli outlet at California’s Buena Park

The Yellow Chilli outlet at California’s Buena ParkPhoto Courtesy: Sanjeev Kapoor Restaurants Pvt Ltd

But television was no longer the only screen audiences were hooked to; social media had happened to India. In 2009—in a world where Facebook, YouTube and blogs were changing how people searched for and shared information—he launched Sanjeev Kapoor Khazana, his YouTube channel, which, to date, has more than 2.5 million subscribers and 617 million views; his website, sanjeevkapoor.com, claims to have 10 million page views per month, while his Facebook page, started in 2009, has 5.3 million followers.

As his popularity continued to spread, in 2009, along with Ravi Saxena, co-founder and former CEO of Sodexo India, Kapoor started Wonderchef, a range of non-stick cooking pans imported from Italy. And if all these businesses were not enough to keep him occupied, he has written more than 200 cookbooks, mostly in association with Popular Prakashan, which have sold more than 10 million copies.

All of this has been powered significantly by the cult of his personality. Perpetually seen with a congenial smile, Kapoor is a celebrity—he ranked 34th on the 2017 Forbes India Celebrity List—unlike many others. “I think I don’t make people feel threatened in any way,” he says. “And I have never erected any barriers between myself and people; I have never had bodyguards. Between the people who appreciate and like my work, and me, there has always been a feeling of apnaapan [oneness].”

“Sanjeev is an extremely good chef, but being a good chef is not enough to reach the heights that he has,” says Anjan Chatterjee, founder and managing director of Speciality Restaurants. “His competency lies in his communication skills; he makes everything sounds simple, he is always smiling, and is very likeable.” Chatterjee narrates an incident from a decade ago when he and Kapoor were travelling to Kolkata for a promotional event. “At the airport, he was met by a throng of women who were so excited to see him! I had to somehow take him to the car, amid fans chanting ‘Sanjeev, Sanjeev’. Even at my restaurant Oh! Calcutta, he was slipping out of the lobby when waiting guests saw him and they all wanted to click a photo with him or greet him.”

As his popularity continued to spread, in 2009, along with Ravi Saxena, co-founder and former CEO of Sodexo India, Kapoor started Wonderchef, a range of non-stick cooking pans imported from Italy. And if all these businesses were not enough to keep him occupied, he has written more than 200 cookbooks, mostly in association with Popular Prakashan, which have sold more than 10 million copies.

All of this has been powered significantly by the cult of his personality. Perpetually seen with a congenial smile, Kapoor is a celebrity—he ranked 34th on the 2017 Forbes India Celebrity List—unlike many others. “I think I don’t make people feel threatened in any way,” he says. “And I have never erected any barriers between myself and people; I have never had bodyguards. Between the people who appreciate and like my work, and me, there has always been a feeling of apnaapan [oneness].”

“Sanjeev is an extremely good chef, but being a good chef is not enough to reach the heights that he has,” says Anjan Chatterjee, founder and managing director of Speciality Restaurants. “His competency lies in his communication skills; he makes everything sounds simple, he is always smiling, and is very likeable.” Chatterjee narrates an incident from a decade ago when he and Kapoor were travelling to Kolkata for a promotional event. “At the airport, he was met by a throng of women who were so excited to see him! I had to somehow take him to the car, amid fans chanting ‘Sanjeev, Sanjeev’. Even at my restaurant Oh! Calcutta, he was slipping out of the lobby when waiting guests saw him and they all wanted to click a photo with him or greet him.”

Image: Joshua Navalkar

But is this what he always wanted to do? The son of a banker, born in Ambala, who had considered studying architecture in college, had been fond of cooking right from the beginning. But the only reason he opted for the kitchen and not the front desk after completing his hotel management degree was because he wanted to do something his friends weren’t doing.

Not doing what others did was also the reason he began to give cooking lessons while working as a chef in a Varanasi hotel in the mid-1980s, and later when he worked in New Zealand and at Mumbai’s Centaur Hotel. Sharing their knowledge and skills went against the grain of most chefs who jealously guarded their secrets and tricks of the trade.

Being a chef and a businessman may not be much of a novelty today, when a new crop of chef-entrepreneurs are gaining prominence. But in the India of the 1990s, this wasn’t the case. “In my mind, I was always an entrepreneur; that was the spirit with which I worked, even when I was in hotels,” explains Kapoor. “There was no transition of thought. It is not something that has changed over the years. Earlier I would work for hotels and restaurants, now I work for my company.”

How is it, though, to manage the creative aspects of being a chef, and the hard-nosed commercial aspect of being a businessman? “Being a businessman and being a chef coexist,” he says. “If you are cooking something, and not as a hobby, then it is a business. If you are a chef, you cook to sell. You may not be selling it yourself, somebody else might be doing that for you.”

But managing the left and right hemispheres of his brains has not been an easy task. “Being a chef, a creative person, is individualistic in nature; you shine because of your individuality. But in business, it is not about an individual, it is about the collective team effort,” he says. While for a creative person, the vision is fluid and not cast in iron, for a businessman, he is supposed to know exactly what he is doing. “That understanding and respect, and its importance, have taken some time for me to put together and get right.”

Some recipes do take a while to perfect.

Not doing what others did was also the reason he began to give cooking lessons while working as a chef in a Varanasi hotel in the mid-1980s, and later when he worked in New Zealand and at Mumbai’s Centaur Hotel. Sharing their knowledge and skills went against the grain of most chefs who jealously guarded their secrets and tricks of the trade.

Being a chef and a businessman may not be much of a novelty today, when a new crop of chef-entrepreneurs are gaining prominence. But in the India of the 1990s, this wasn’t the case. “In my mind, I was always an entrepreneur; that was the spirit with which I worked, even when I was in hotels,” explains Kapoor. “There was no transition of thought. It is not something that has changed over the years. Earlier I would work for hotels and restaurants, now I work for my company.”

How is it, though, to manage the creative aspects of being a chef, and the hard-nosed commercial aspect of being a businessman? “Being a businessman and being a chef coexist,” he says. “If you are cooking something, and not as a hobby, then it is a business. If you are a chef, you cook to sell. You may not be selling it yourself, somebody else might be doing that for you.”

But managing the left and right hemispheres of his brains has not been an easy task. “Being a chef, a creative person, is individualistic in nature; you shine because of your individuality. But in business, it is not about an individual, it is about the collective team effort,” he says. While for a creative person, the vision is fluid and not cast in iron, for a businessman, he is supposed to know exactly what he is doing. “That understanding and respect, and its importance, have taken some time for me to put together and get right.”

Some recipes do take a while to perfect.

X