Rich Frank's Champagne Tastes

A Hollywood insider puts American ‘grower Champagnes’ in the spotlight

“If you want to make sparkling wine good you’ve really got to put your mind to it,” says Rich Frank, owner of Napa Valley’s Frank Family Vineyards and a man who has tackled a few complex productions in his career. His résumé as one of Hollywood’s long-running inside players, still unscrolling at age 70, includes nearly a decade as president of Walt Disney Studios, president of Paramount Television, and leading roles as a mover behind familiar titles, from Cheers, Home Improvement and Entertainment Tonight to Pretty Woman, Good Morning, Vietnam, and The Lion King.

But Frank Family Vineyards, the winery he bought—almost by accident—in 1991, is Frank’s auteur piece, his brainchild from beginning to end.

Though primarily known for its cabernet sauvignon, Frank Family is playing a key part in an under-the-radar development in American wine: The green shoots, here and there, of a movement to make artisan sparkling wines similar to the French farmer-made Champagnes that have become the darlings of international connoisseurs.

Exactly how similar these homegrown sparklers might be is a matter for debate. Frank Family winemaker Todd Graff puts it this way: “The grower-producers have gotten hot in Champagne, but we aren’t trying to copy them. I’d say we are trying to be equal with them.” But the French inspiration, right down to the maverick sense of being a surprising one-off, is evident in the idea.

Until a few years ago, the notion of a small Champagne grower bottling his own wine carried the iconoclastic shock of the runner heaving the sledgehammer at Big Brother in the famous Macintosh ad. In France, nearly all the Champagne is bottled by big houses—the Möet et Chandons, the Veuve Clicquots—that buy their grapes from thousands of independent growers. The Enshrined Idea is that the best Champagne is created by blending, blending, blending all those grapes, to evolve a house style that will be consistent across vintages. This is not a bad idea, as far as it goes: After all, Roederer Cristal tastes pretty darn good, bottle after bottle, with its own identifiable weight and complexity.

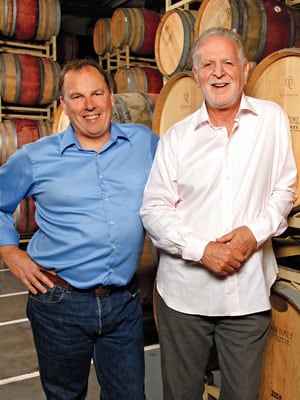

Image: David Arky for Forbes

But what if you, a grape farmer, felt that your own 4 hectares yielded strikingly particular wines, and it pained you to have their personality submerged in some grande marque’s blending tub? You might launch yourself onto the uncertain waters of the market under your own brand, like such ‘farmer fizz’ labels as Jacques Selosse, Egly-Ouriet and René Geoffroy. You might say, vive la difference! Let a thousand flavours bloom! Let the consumers figure this out if they can!

This was not exactly what Rich Frank had in mind in 1991 when Koerner Rombauer called him at home at midnight and said, “Let’s buy a winery!” Rombauer, a Napa vintner, was a good friend, so Frank was listening. The property in question was the well-known sparkling wine producer Kornell Champagne Cellars, which had fallen on hard times and was now in the hands of its bankers. Then things got urgent.

“It was a strange story,” Frank remembers. “A local bank had the foreclosure documents but was being bought by a national bank, and the national bank was not allowed to own a liquor licence. And, of course, they don’t tell the local bank what’s going on. So suddenly they have to sell this winery in 24 hours.” To appease Rombauer—and possibly to get back to sleep—Frank said, “Offer them half.”

“I figured I had kept a friend, and that would be the end of it. But Rombauer called me the next day at noon and said, ‘We own a winery’. And I said ‘That’s great. Now can I see the books?’ It turns out they were selling 100,000 cases a year in supermarkets, and for each bottle they were losing like $3.”

In that first year, 1992, the newly-minted Frank Family Winery scaled production back to 200 cases, charged an appropriate price and was off to the races. “We actually made money the first year,” says Frank, “and we’ve been making money ever since. We’ve just let it grow, with the customers pulling us through; we’ve always been happy to run out of wine in 10 or 11 months.” This year, Frank expects to bottle—and run out of—100,000 cases.

Though only about 5,000 cases will be sparkling wine, the successor winery to Kornell’s old ‘California Champagne’ facility still has bubbles on the brain. The sparklers are a signature offering in Frank Family’s tasting room, a facility that is the subject of much of the winery’s sales focus. And then there is Graff, who spent 10 years crafting sparkling wine at Schramsberg and Cordoníu Napa. “If you talk to Todd,” acknowledges Frank, “the first thing that comes out of his mouth is ‘the bubbles’; he loves them.”

Unlike his old employers who adhere to the grande marque model, sourcing base wines from 90 vineyards in northern California, Graff is consciously following the French grower model, utilising grapes only from Frank Family’s vineyard in the cool Napa Carneros. “It gives us very bright, beautiful fruit,” he says. But in his view, the terroir argument—that the locality of the grapes should speak—is only part of the upside of being a small-scale grower-producer. “Our sparkling wines have a character that builds over the length of ageing,” he explains. “Because we’re not competing to rush it to the shelves, we can give it extra time.” Frank Family allows its Blanc de Noirs and Blanc de Blancs (each $45) three years (versus the mandatory one) to mature, and its Reserve bottling ($95) five years. In other words: “It’s by our rules only.”

Frank Family is among the most visible of the small group of American ‘grower Champagne’ producers, boosted by the firm advantages of a sparkling wine facility and heritage (with built-in customer base), an expert sparkling winemaker and Rich Frank’s deep wallet. Fine sparkling wine is expensive to make. Explains Frank, “You make the wine once, then you make the wine a second time”—by refermenting it in the bottle—“and by law you have to let it lay for a year, and we let it lay longer. You have a lot of money tied up.” As a rough estimate, Frank says the $100 you might spend making a case of still table wine climbs to $120 to $130 for sparkling (and that doesn’t include the excise tax—four times that for table wine—which adds another $9). And the potential market is not exactly gigantic. All the bubbling wine sold in the US in 2011, from Dom Pérignon to cold duck to prosecco, amounted to less than 6 percent of the volume of table wine.

Despite significant discourage-ments to entry, there are dedicated small-scale American producers whose wines readily deserve a seat at the same table as fine French grower Champagnes. In Oregon, that includes Argyle and Soter, both bottling estate-grown wines, and cool-climate producers in California like Merry Edwards, Kalin, Richard Grant, Thomas George and Sea Smoke. “There are only a few of us,” says Kathleen Inman, a former corporate finance executive who makes elegant sparkling wine at her Inman Family winery in Sonoma. “But just over this past harvest, I’ve heard about more people getting the idea that it would be fun to make single-vineyard sparkling wines. Why not? Sparklers with ‘a sense of place’, you know?”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)