James Patterson: A mastermind of thrillers, and marketing

James Patterson, one of America's largest selling thriller authors, aims to purloin some Indian readers. And Ashwin Sanghi is his able accomplice

Somewhere in Palm Beach, Florida, in a $20-million mansion, a 66-year-old man paces restlessly. The room is lined with overflowing bookshelves. Stacks of papers, meticulously categorised, front pages labelled in large lettering, fill the lower shelves. A fax machine sits in a corner, for detailed communications with strategically-picked accomplices across the world. Outside, in the pre-dawn darkness, across the perfectly manicured lawns, you can hear the rustling of palm fronds and the gurgling sea.

In his hands he has a sheaf of type-written paper, picked up from a middle stack on a lower shelf. He reads, he scribbles along the margins. He sips on his coffee. His mind conjures up a twist; one that he knows—he has done this so often—will hook his victims.

Meanwhile, in tony South Mumbai, in a bungalow behind high walls and guarded gate, a 45-year-old man sits in his den, adjacent to, and several highly-polished wooden steps below, the family living room; the rest of the house has settled in for the night. The wall behind him is covered with books and movies he has cherished since childhood. The blue light of the computer screen reflects off his glasses. He slips into his alter ego, and his mind whirrs into action. His fingers fly across the keyboard: The twist the mastermind had dreamt up must be worked into the plan.

It’s a modus operandi that has worked before. Very well. No reasons why it shouldln’t work this time.

James Patterson, one of the largest-selling thriller writers in the US, has his name on the front of more titles than would fit into a neighbourhood library: At last count it was close to 130. By the time you read this, there will probably be a few more. Apart from being immensely popular in the US—one in 17 hardcover thrillers read in the country is a Patterson—he is also a regular bestseller in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, with strong sales across Europe.

Some more staggering statistics: $700 million (his earnings over the past decade), $90 million (his earnings between June 2013 and June 2014), 300 million (the total number of copies he has sold worldwide), 10 million (the number of ebooks he has sold), and 76 (the number of No. 1 New York Times hard-cover bestsellers he has written, the most by any author). In an interview with The World Over, a show on US TV channel EWTN, he said that one of the “crazy statistics” his publishers came up with is that he sells more books than John Grisham, Steven King and Tom Clancy combined.

Success didn’t come overnight. Although he began writing fiction in 1976—his first novel The Thomas Berryman Number won the 1977 Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best First Novel—it was only in 1993, after six more novels, that he found fame and commercial success with Along Came a Spider, the first in his Alex Cross detective series. He was merely prolific until 2003, during which time he published between one and three titles a year. From 2004 onwards, ‘frenetic’ would perhaps be more accurate, with more than five titles a year. From 2010 onwards—with as many as 13 titles in a year—it has been, simply put, off the charts.

Patterson’s talent and untiringly fertile mind aren’t the only factor at play; what makes this speed possible is the collaborative model he has mastered. Starting with one co-authored book in 1996, he has written up to 11 co-authored titles a year since 2011, all building the highly successful Brand Patterson. Taking pages out of textbook lessons on brand building, he has expanded his ‘product range’ and ‘product line depth’.

That range now occupies quite a few market niches. It includes the dozen series he has built since the first Alex Cross in 1976, each one targeting a slightly different category of readers, or dealing with a different theme. The Alex Cross series, for instance, is rooted in America (it is also the only series that Patterson does not co-author with anyone else), while the Private books, also crime thrillers, are international in character (with co-authors from different countries collaborating on country-specific plots), and Women’s Murder Club has a group of women taking up crime-solving. And it’s not just crime; he’s got something for everybody: The I, Funny series for children, the Middle School series for adolescents, the Maximum Ride series for young adults, and even some romance.

And his product line runs deep: Alex Cross has 22 titles, Women’s Murder Club 13, Middle School 6, and so on.

It may sound heretical to use terms like this when referring to books—and, to be sure, Patterson does not—but it’s insructive to note that he cut his teeth on these concepts. He was CEO of JWT, North America (JWT is one of the largest advertising agencies in the world) until 1996, spending close to 25 years in the ad business. He also made the uncommon transition from the creative side of advertising—he started out in 1971 as a copywriter—to the corner suite.

Patterson, however, speaks of that phase like it was a bad habit he has kicked; he claims he’s “been clean for a long time”, something he has said in earlier interviews as well. “I was very good at [advertising], but I didn’t have much interest in it. My background was more literature and English [he was a PhD candidate at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee] than ad. I just happened to pass through there, and it paid the bills. It’s kind of bizarre when you land up being the CEO of J Walter Thompson of North America, but it was always something that I did… One of the reasons I never had a stress on my writing is because I always had a paycheque coming in.”

He did like some parts of his job, though. “I didn’t love the craft of advertising. Once I got to hire people, I hired only one kind of person: Talented and nice to be around. So, it was a very nice staff. They were bright, and very nice people. And we would go and make these little movies, 30 seconds, 60 seconds. And it was fun.”

Those fun ‘little movies’ were one of the first things he brought to the quiet world of books. Long before any publisher had heard of video ‘trailers’ for books, Patterson made one to market Along Came a Spider in 1993. “It was something that his publisher had refused to do, so he did it himself,” says Caroline Newbury, vice president, marketing and corporate communications, Random House India.

Seventeen years later, the same tool was employed by Amish Tripathi for his Immortals of Meluha, in 2010. “When I did video promos of my first book, based on a suggestion from my friend Abhijeet Powdwal—and it had seemed to work quite well—I did not know that Patterson had done the same for his books,” says Tripathi, adding, “I did not know Patterson was an ad man, but now that I know, no wonder then.”

Authors devising marketing plans—or, for that matter, actually getting involved in the marketing at all—is a relatively new phenomenon in India. Tripathi’s marketing acumen and path-breaking ideas have made quite a few reconsider their aversion to promotion.

“Initially I belonged to the school of thought that a good book should sell itself. But now I have changed my mind, and I feel that even a good book needs to be marketed well,” says Mita Kapur, founder and CEO of Siyahi, a literary consultancy. “Now there’s a beginning. But everybody is not as smart as Amish was. He was spot on.” Kapur highlights the instances of comedian and author Sorabh Pant, who is promoting his book through his stand-up act, and adman Pratik Kamat, who is making promotional videos for his books.

In the constant and evolving fight to hold on to shelf space, “it’s very useful to join forces as it were, to tap into the author’s resources and network—to make the most of every opportunity so that the book is visible, talked about and sold as best as it can possibly be,” says Diya Kar Hazra, Publisher (Trade) at Bloomsbury India. “One has to constantly come up with new, exciting ways of publishing. Authors are very savvy now—technologically; in terms of media and publicity—and many of them like being involved in marketing their own books.”

Authors becoming brands unto themselves is useful not just for the author but also readers, says R Sriram, co-founder of Crossword and founder of Next Practice Retail, a business consultancy. “And authors like Patterson are constantly trying to expand to new geographies. Partnering with Ashwin Sanghi is a smart move.”

But marketing his books is just one aspect of Patterson’s work. First he needs to write them. And for this he has evolved a method that has stood the test of time: Writing with co-authors.

His first co-authored book was in 1996, Miracle on 17th Green. “While I was [at JWT] a friend of mine wrote a lot, he used to write for the New York Times. I said, I have an idea for a novel about golf—we used to play golf together—and I told him the story. And he said, why don’t we try to write it together? So that was the first one. And I enjoyed it.”

Judging by the speed of his output, he has mastered the art of collaboration, often writing with co-authors in different countries.

How does he choose his partners? “You want to see that the writer is in tune with what [you] do. My style is very colloquial, verbal; there’s not an excessive amount of detail, because that is not how we tell stories to each other. [It’s] how you involve your reader and how important it is that you keep putting out questions that the reader must have answers to. If readers figure out the mystery two-thirds of the way through the book, you might as well throw the book away. So it’s important that the writers I work with have the sense of suspense. And character. I think that is probably one of the strongest things when I read some of Ashwin’s [Sanghi] stuff. And I feel readers around the world would want to read another book with that character.”

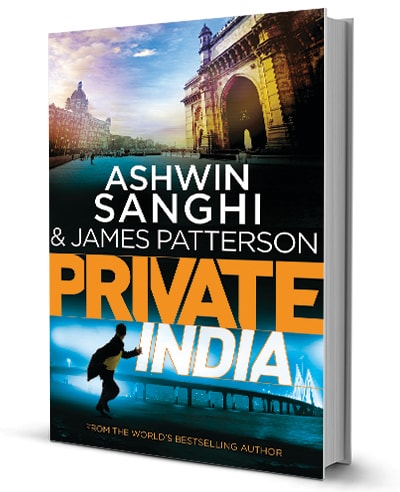

The Sanghi partnership belongs to Patterson’s Private series of books, which revolves around an international crime-solving agency with offices in different countries. So, there’s a Private London, Private Berlin, Private Down Under, Private Paris. And now—in a first for an emerging economy—Private India. (Private Rio is in the works. And Private China, Patterson says, could, some day be a possibility.)

Patterson and Sanghi have yet to meet in the flesh. Serendipity, says Random House’s Newbury, was the key. “Patterson’s group of editors sits very close to where Sanghi’s editor sits in our London office, and they were discussing which Indian author could co-write Private India. Sanghi’s editor suggested his name, and that is how it all began.”

“[Sanghi] plots very well,” Patterson says, “He is very organised before he starts to write the book, in terms of the outline, very involved and logical. He does a nice job of characters,” says Patterson. “The only stylistic difference is he is more inclined to do 700-page books, I am more inclined to do 400-page books.”

A detail not lost on Sanghi: “On my previous novels, I have written about 130,000 to 140,000 words and typically the plot outline had been 2,000 words. This is a novel running into about 75,000 or 80,000 words, but the plot outline ran into about 13,000 or 14,000 words.”

Sanghi brings to Private India far more than what a co-author usually contributes to Patterson’s novels. (Which might be the reason why his name appears in a larger font than Patterson’s on the cover, a deviation from the usual format.) In a typical co-written work, Patterson does the plots. Plot—as anyone who has read him will know—is key to the story; it is the subject of vast amounts of correspondence with his co-authors and many iterations. For Private India, in another deviation from the usual model, Sanghi has provided both plot and research. “That’s him. He’s the star. I’m the helper in this case,” concedes Patterson.

Sanghi says, “I think [Patterson] was aware of the fact that I have already done several books here in India, and he was very focussed on having the Indian sensibility come through. He said, ‘You give me the idea.’ Once I had that idea, then he said, ‘Okay, why don’t you send me the plot outline?’ That ended up taking up almost six months.”

Co-authorship is, however, not everyone’s forte. Tripathi, for instance, says, “I don’t think I would be able to work with the co-writer model. I am a control freak, and I cannot imagine working with someone else. I want to tell the story my way. There is nothing better or worse about this model, it is just a different path.”

Sanghi seems to have enjoyed it, and is glad to have broken form after three mythology-based bestsellers. “Patterson and I came together because both of us are fond of thrillers. And pace and plot are key elements. That common DNA is very much there. But what is different for me this time, is that history and mythology do not form the core of the material. Mythology tends to be incidental to the plot.”

“He has done this a million times. He has got it down pat as a formula, this will work and this won’t work,” says Sanghi. “There is a reason why he has been so successful. There is that old proverb which says easy reading is damn hard writing. That ability to make it a very easy read, and the formula that ensures that the page turns itself, that is the critical element of a Patterson book. But, I knew at the end of the day, this is not going to be an Ashwin Sanghi book, it will be a James Patterson and Ashwin Sanghi book.”

And it is a James Patterson and Ashwin Sanghi book. Starting in Mumbai, with a dead body hung up behind the door of a bathroom in a posh hotel, the story is fast, littered with twists and bends in plots and ploys, Patterson’s trademark single-paragraph chapters, with ample dangling hooks to snare the reader. The protagonist is Santosh Wagh, a private investigator who has Johnny Walker for his best friend. Sanghi’s familiarity with the Indian context shows through in the research, the characterisation, and the minute detail.

The mastermind sits back, surrounded in his lair by intricately crafted plots that will soon be the spines of new bestsellers. It’s been a long journey from that first book, from writing on time stolen from the day job. So many words, so many books.

Most would be glad to have one decent career; his second innings was even more successful than the first. A man could sit back, content…

He looks, past his private lawns and pool, on to the breaking day.

It’s time, he thinks. Time to plan the next caper.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)