Indians have gotten used to buying art online: Saffronart CEO

Co-founder Dinesh Vazirani talks about running India's first online art auction house in the age of internet and smartphones

Dinesh Vazirani, the co-founder and CEO of Saffronart

Image: Courtesy Saffronart

Image: Courtesy Saffronart

Saffronart, India’s first online art auction house that started in 2000, will host its 200th auction on June 13 and 14, with 150 works of modern and contemporary Indian art. Founded by the husband-wife duo of Dinesh and Minal Vazirani, it has galleries in Delhi, Mumbai, New York and London, and now conducts physical live auctions, along with their online events. Apart from a smartphone app that it launched in 2009, Saffronart started StoryLTD in 2013 for collectibles at a lower price point.

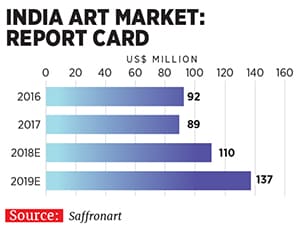

In an international art market, where technology plays an ever-increasing role in acquiring new customers, Saffronart finds itself in an industry where the global traditional heavyweights such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s are adapting to online auctions. In February 2017, Christie’s reported an 84 percent rise in online sales to £49.8 million, even as its overall sales fell by 16 percent to £4 billion. According to the 2018 Hiscox Online Art Trade Report, online art market sales reached an estimated $4.22 billion in 2017, up 12 percent from the year before; this was, however, lower than the 15 percent year-on-year growth rate in 2016, and 24 percent growth rate experienced in 2015. Texas-based Heritage Auctions—one of the largest online sales platforms for art and collectibles—saw sales grow by 25.8 percent, from $348.5 million in 2016 to $438.3 million in 2017.

The Hiscox report adds that despite the online art market growing around 20 to 25 percent between 2013 and 2015, the last 24 months have shown signs of a slowdown, perhaps because the industry is struggling to broaden and grow its online client base. The transition between offline and online is proving to be a challenge, and while parts of the industry (auction houses in particular) have been rapidly adapting to a new digital era, other players such as galleries and dealers are still getting to grips with the digital market.

In an interview to Forbes India, Dinesh Vazirani, the 51-year-old co-founder and CEO of Saffronart, talks about the auction house’s journey and the way forward. Edited excerpts:

An untitled painting by Subodh Gupta that will go under the hammer in the June auction

An untitled painting by Subodh Gupta that will go under the hammer in the June auction Image: Courtesy Saffronart

Q. How have the online art auction markets in India and abroad evolved?

The Indian online market for art has been around for a long time. We started it in 2000, and we were purely an online place at that time. People in India have gotten used to buying art online. This is different from other countries, where there are physical auction houses first; online auctions came later.

Today, people don’t make any distinction between buying art online, or in a gallery, or at a physical auction. The market has matured enough, and people are confident in the transparency, openness, ease of use and access that an online platform provides. Buyers now transact online even for amounts like $2-3 million dollars, or more, on a single painting. The positive experiences that people have had online have also helped build the market.

Q. Have traditional art buyers taken more time to adapt to online in terms of monetary transactions?

In auctions, there is no cash involved; it’s purely an electronic or cheque payment. Over time, people have become more comfortable with that mechanism; with these transactions, there is full recourse, in the event of authenticity [issues], or if something goes wrong with the painting. There is a comfort level for a product where provenance is so important.

Q. Sotheby’s and Christie’s have started online auctions whereas Saffronart now has physical auctions as well. Is there one medium or method that is set to dominate the others?

It is actually a convergence between all the different media. And everything is converging on our mobile phones. Even a physical auction today has live video streaming. So buyers have the option of being in the room, on the phone or online. The model has truly become a hybrid one.

In the online model, the pool of people who participate is bigger. Earlier, when there were physical auctions with no online plug, it limited the number of participants because people would have to come to the venue. The internet gives free access to people who we approve, and they can be from anywhere. Traditionally, the online platforms would see more participation, but because of the hybrid model, they are now on a par. But the online model is definitely cheaper.

Q. What are the differences in bidding patterns between online and physical auctions?

Online auctions run for something like two days, while physical auctions go on for two hours. So, in online auctions, people have more time to think about what they want to bid for, and evaluate their decision, which is less in physical auctions. The time available itself changes things… it gives buyers the space to think about additional costs, or look for something in the next lot. In an online auction, you get more educated bidders who have the time to think about what they want to do.

In live auctions, things move really fast. You have to make a decision in a second or the hammer’s down. In an online auction too, on the last day, you can see the excitement on screen.

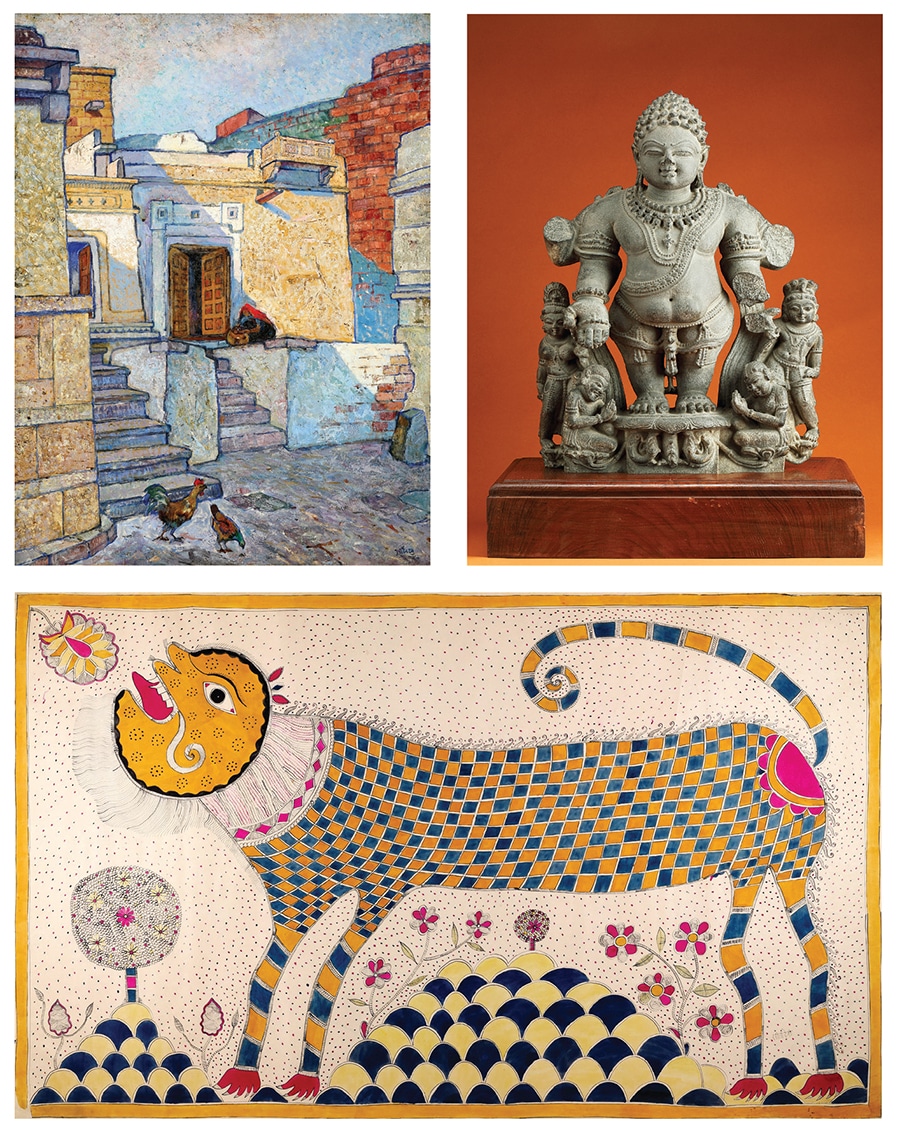

Clockwise from top left: A painting by Madhav Satwalekar, a statue of the Vamana Vishnu and a Sita Devi Mithila work had sold for record values at previous Saffronart auctions

Clockwise from top left: A painting by Madhav Satwalekar, a statue of the Vamana Vishnu and a Sita Devi Mithila work had sold for record values at previous Saffronart auctions Image: Courtesy Saffronart

Q. In a live auction, there is a rationale behind sequencing lots from the same collection, or from the same artist. How do these dynamics change online?

For our June auction, there are 150 lots, and we have five different closings. So lots are bunched together in groups of 30, and they close at a certain time. Unlike a live auction, where you have one lot at a time, online you have 20 or 25 lots closing at the same time. There is a different energy level. And you distribute your lots according to that; you don’t put all your good lots in one closing. You will place some low-value and some high-value lots in the same closing.

You obviously would like lots to sell in the beginning, so the first few lots may be of lower value, and they pick up momentum later.

Q. Are there specific regions from where you see your highest bids and purchases?

The two major regions would be India and the US; there is Europe and the Far East as well, but they lag behind the first two. The Middle East has picked up a lot; it is a place where Indians are getting active, and where they reside after buying homes.

In the US, the concentration is more on the East Coast. People in private equity and hedge funds have always been big buyers of art, not just Indian art, but also Western art. So it’s a combination of a concentration of wealth, and a concentration of Indians. For the Indian art market, in general, about 20 percent or less of the buyers would be non-Indians.

Young buyers are coming into the market at lower price points, of course, because they are starting off. But the predominant buyers of the big Indian painters, the pricier ones, would be between 45 and 65 years old.

Q. What is your opinion about Christie’s exit from India, and the entry of Sotheby’s?

Christie’s exit from India was a global decision; it decided it did not want to focus on its non-core markets. Sotheby’s, sensing Christie’s exit, has latched on to the opportunity. From a market perspective, it is great that Sotheby’s is coming to India. It is one of the largest auction houses, and has been around for 200 years. Sotheby’s coming to India is almost like a stamp of approval and endorsement for this market.

The first has been to deal with both success and failure; there have been ups and downs in the last 18 years. The market itself has gone through different cycles. In good times [one learns] to understand how to expand the market, and in bad times, how to operate [within] certain boundaries.

The second and the biggest learning has come from the opportunities to interact with many different artistes and creative people. These interactions offer so much to learn about their art, and their inspirations.

The third learning has been how to grow a global organisation, with galleries in New York, London, Delhi and Mumbai. And build a team that achieves the goals that you have set out.

Q. What have been the highest and lowest points of running Saffronart?

The lowest point was in 2003, when we almost shut Saffronart down. There was no market; it was not developing, and we had spent too much money, our expenses were very high. Although it was the lowest point for us, Minal and I had the courage to say, “Okay, let’s give it one more shot. Let’s borrow money and put in our resources.” So the decision we made at our lowest point was actually the best one we made. Because everything turned around; the market came back.

The high point was 2006 and 2007 when for every painting there were 10 people wanting to buy it. There was such a frenzy that everyone wanted to buy art. And people thought if they were not buying art, they were missing out on something. That manic phase was the most exhilarating part of running Saffronart.

Q. What’s next for Saffronart?

It has to be technology and innovation given the way the world is moving. It would be about greater access, integration, convergence; the experience that we would like to give users, whether they are bidding from their mobiles, computers or other devices. Innovation within technology will bring in new buyers because access becomes a lot easier.

We will also look to develop markets through events such as seminars and discussions. It would be about giving enough knowledge to buyers so that they can make educated decisions. We have been eyeing two or three markets over the last few years: One is the antiquities market, second is folk and tribal art, which is our own indigenous art that is overlooked, and of course there are smaller categories such as books.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X