Gandhi Out of Africa

It is in the details that the spirit of the Mahatma lives on in Johannesburg

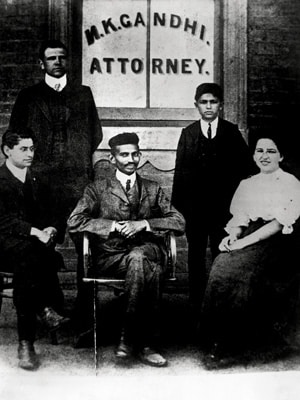

The name rang a faint but distinct bell. Familiar, but why? The photograph shows a dapper young man wearing a buttoned-down jacket with angled lapels, hair parted neatly on the left, head tilted ever-so-slightly to the right. This was Nagappen Padayachee, from 1909.

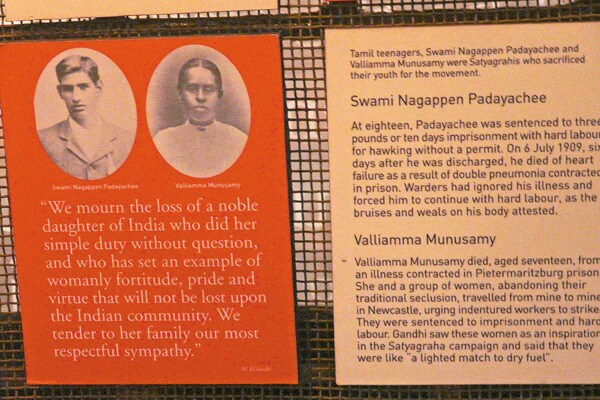

An immigrant to South Africa from Tamil Nadu, Padayachee was arrested in June that year for hawking without a permit. His sentence: 10 days in prison with hard labour. With the conditions, and then being forced to walk to a camp 26 km away, Padayachee fell ill. Six days after he was released, he was dead. “Warders had ignored his illness,” said the few lines beside the photograph, “and forced him to continue with hard labour, as the bruises and weals on his body attested.”

Five years later, a man called Mohandas Gandhi unveiled memorial tablets to Padayachee and a woman called Valliamma Munusamy at Johannesburg’s Braamfontein Cemetery. The tablets remembered both as martyrs to the struggle for equal rights in South Africa. For Gandhi, they were inspirations, “like a lighted match to dry fuel”.

Dead at 18, remembered by his home country’s most famous son: This dapper youth must have been quite a figure among Indians in South Africa in the early 20th century. But I had never heard of him. So why did “Padayachee” ring a bell?

It came to me several minutes later, and I actually ran back to look closely at the photograph. Usually spelled “Padayachi”, it’s my Tamil grandfather’s caste name. Here it was, in a museum in Johannesburg. Given how these things work, it’s even possible that I am related to this young martyr. Was he a cousin once-removed, something like that? No way to answer that, of course. Nevertheless, I stood there a long time, transfixed. What a thought. A possible personal connection, going back a century, to the battle against apartheid: What a thought.

Image: Roger de la Harpe / Corbis

The Old Fort on Johannesburg’s Constitution Hill was formerly a prison. Today, it is a museum and a landmark. Both Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela were held here

The museum is in the cell where Gandhi was once incarcerated, on what is now known as Constitution Hill. There was a notorious jail here through the apartheid years, always called ‘The Fort’. After a new South Africa was born in 1994, most of the Fort was demolished to build the country’s highest court, the Constitutional Court. As an Indian used to layers of security, even secrecy, that blanket our public institutions, it was startling to simply walk into this place. I mean, I strolled right into the cavernous yet cozy chamber where the senior-most judges of South Africa listen to arguments. I could have sat in their chairs.

Outside the chamber is a panel with fetchingly informal portraits of the judges who have sat, more legitimately, here. For me, the lone familiar name was Albie Sachs. Being something of a compulsive reader about apartheid, I still remember the 1988 bomb placed by his own country’s police that ripped off his arm and destroyed his eye. What a place South Africa once was. But also being something of a compulsive follower of cricket, I know of his recent role on the tribunal that inquired into match-fixing. Something discordant about juxtaposing a bomb and cricket? But that’s South Africa.

South Africa, where a prison morphs into a supreme court.

Also outside that chamber is a wall with photographs and quotes from several landmark judgements that this court has delivered. The idea of the wall — indeed of the airy building itself — is many-faceted, said Kalim Rajab, our South African-Indian friend who drove us here. For one, spell out the thinking behind a new Constitution for everyone to see and understand, so they can appreciate their stake in the country. For another, make justice more transparent than it had been for years, than it otherwise might come to be. In general, encourage clarity and candour about the working of the judiciary, so it doesn’t turn remote, abstract.

Out of the rubble of oppression and brutality, rebuild with openness and foresight: What a place South Africa once was, but what a place it is striving to be.

On the wall, it’s spelled out in red letters: “The first of the founding provisions in the Constitution defines South Africa as a state founded on the values of human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms.”

The words stopped me in my tracks just as surely as “Padayachee” did. In particular, there’s “the achievement of equality”. How easy it is to assume, and airily pronounce, that we are all equal. And yet this country was once a living testament to the ease, instead, of institutionalised inequality. A testament to the brutality that consumes those who assume superiority by virtue of something as trivial, as foolish, as skin colour. In some elemental way, these words drove home just how foolish. Imagine an entire edifice of law and governance built on, let’s say, thumb length: The longer, the more exalted. Or earlobe fleshiness: The more succulent, the less privileged. You smile indulgently, but how is either a worse determinant than skin colour — or caste, or faith — of your place in society?

Yet this wall was about so much more than skin colour and apartheid, while drawing nevertheless from the lessons of that dark past. It’s not just racism that South Africa is trying to awake from. Take for example the board titled “Landmark Case: Hoffman v South African Airways, 2000”.

Jacques Hoffman was HIV-positive, and SAA refused him employment for that reason. After hearing arguments, the Constitutional Court directed SAA to hire him, with these remarks:

“Prejudice can never justify unfair discrimination. This country has recently emerged from institutional prejudice… Our constitutional democracy has ushered in a new era… characterised by respect for human dignity for all human beings. In this era, prejudice and stereotyping have no place. Indeed, if as a nation we are to achieve the goal of equality that we have fashioned in our Constitution, we must never tolerate prejudice, either directly or indirectly.”

That word “achieve”, again. No, you don’t assume equality, whether it’s to do with skin shades or with a virus infection. Via constant struggle, and with occasional reminders like on this wall, you work to achieve it. Maybe you’ll never quite get there — which society has? — but the battle for equality is itself worth cherishing.

So it was appropriate that they remember Gandhi on Constitution Hill. To go with thoughts of achieving equality swirling through my head, his famous words made the rounds too: “Mera jeevan hi mera sandesh hai [My life is itself my message].” We may never reach that utopia where all those nice phrases from all our Constitutions hold true in full measure. But the road we take is the point. The life we lead is the point. There’s the message.

For me, from a country wracked with corruption and widening faultlines, there are lessons here. I’ve met, heard and read plenty of Indians who are impatient with Gandhi, contemptuous of him. Yet I suspect that he would say even to them, “My life is my message”. Whether we pay attention is up to us. Whether it’s all good is an open question, also up to us. But it’s there all right, lived all right, that message.

Image: Dilip D'Souza

#11 Albemarle, Johannesburg: The house where Gandhi lived between 1904 and 1906

But back in Johannesburg, why was Gandhi jailed here in the first place? There lies a small lesson in the minutiae of apartheid, and a glimpse at the roots of future struggles against oppressive rule.

In 1906, the government of Transvaal — the apartheid-era province that included Johannesburg — published the Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance. If it became law, all “Asians” — which in South Africa meant Indians and Chinese — would have to carry a pass with their fingerprints; they would be segregated at home and work; and there would be no further Asian immigration into the Transvaal. In September that year, Gandhi addressed over three thousand people at a meeting about the Ordinance. Unanimously, they vowed non-cooperation, if and when it became law. They would refuse to “register” for these passes. Their term for this campaign later resonated across the land of Gandhi’s birth too: “Satyagraha”, which they felt better captured the spirit of their struggle than mere “passive resistance”. When the Asians would not register, the Transvaal government arrested several leaders of the movement. It deported some out of the country, and jailed others in the Fort. Gandhi was one.

The secretary of the Transvaal, the future Prime Minister Jan Smuts, entered into famously respectful negotiations with Gandhi. So respectful, that on display in his once-cell are the sandals Gandhi personally made for Smuts, that Smuts returned to Gandhi in 1939 with these words: “I have worn these sandals for many a summer [though] I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man.” Yet for all his feeling of respectful unworthiness, Smuts was also a shrewd politician. He made this offer: If Asians registered voluntarily, he would repeal the law. Naively, Gandhi agreed.

The story goes that this deal with Smuts was so unpopular with Gandhi’s fellow satyagrahis that they beat him up for agreeing to it.

It would not be the only time Gandhi became unpopular for deals made with authority. Arguably, one of those cost him his life. But the episode with Smuts must have taught him a thing or two about shrewdness in political negotiation.

Travelling through South Africa, thoughts of an apartheid past were never distant. Strangely, that meant Gandhi was a fellow traveller too, at least in my thoughts. From his influence on Nelson Mandela, to the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to the astonishing openness of the Constitutional Court: This is a country that tries to keep alive the memory, the ideals, the heritage, of an unusual man. That his preserved cell stands at the nerve centre of South African justice underlines what the struggle against apartheid meant to his life.

It also underlines what Gandhi meant to this country.

“It’s not entirely far-fetched for the new South Africa to claim Gandhi as its own,” writes Joseph Lelyveld in Great Soul: “In finding his feet there, he formed the persona he would inhabit in India in the final thirty-three years of his life, when he set an example that colonized peoples across the globe, including South Africans, would find inspiring.”

What Gandhi meant to this country, indeed.

For some more evidence of that, Kalim took us to Albemarle Street in the Troyeville neighbourhood of Johannesburg. At the corner of Hillier and Albemarle Streets, we stopped to stare at a handsome white house with floor-to-ceiling windows and curves in all the right places. “This is the place,” said Kalim, a small smile playing on his lips. In 1991, an architect bought this property and carefully restored it, believing it was where Gandhi had lived between 1904 and 1906. For that reason, it was declared a national monument in 1994.

So we stared.

Until Kalim — still smiling — told us a charming story of how Gopalkrishna Gandhi, India’s High Commissioner to South Africa in 1996, came to this corner. The City of Johannesburg had invited him to unveil a plaque here, remembering his grandfather’s stay, unwittingly echoing his grandfather’s own unveiling of plaques to Padayachee and Munusamy 80 years before. Except that when the grandson arrived, he looked mildly puzzled and then turned to look up the road. “I think it’s that one,” he said, pointing to #11 Albemarle, a few dozen yards south of the corner. He was right, and the formal plaque ceremony had to be unceremoniously shut down. Pity, that.

Handsome too, though more angular, #11 was indeed where Gandhi had lived in those years, sharing the house with his lawyer colleague Henry Polak. In 2009, the city did the right thing and unveiled a smart blue plaque there: “Johannesburg City Heritage: Gandhi Family Home” it says.

Gandhi: This city’s heritage. This country’s heritage. Our heritage. My heritage. After visiting a once-prison cell, a country’s highest court, a house where Gandhi did not live and now another where he did, I have a good idea why the cell where he was imprisoned has been saved from demolition and filled with Gandhi arcana. (And even his voice, from a 1947 BBC interview.)

Above the passage leading to the cell are Nelson Mandela’s words: “A nation should not be judged by how it treats is highest citizens, but its lowest ones — and South Africa treated its imprisoned African citizens like animals.” Mandela would know, of course, from years imprisoned in the windswept severity of Robben Island. But here on Constitution Hill, in this renovated and sanitised cell that Gandhi once occupied, it’s hard to get a real sense of that treatment.

Though there is that photograph of Padayachee, taken before his body turned into a mass of bruises.

At some point during the apartheid years, somebody vandalised the Braamfontein cemetery tablets remembering Padayachee and Munusamy. Only in the mid-1990s, after apartheid had become the stuff of museums, were the sites where Gandhi had unveiled them rediscovered and restored. It makes you wonder, speaking of heritage: How much did apartheid destroy that needs restoration? How much will never be restored, can never be restored?

He might have been a relative, this Nagappen Padayachee. He also might be no more than a footnote in a long history of apartheid and satyagraha and two different countries’ struggles for freedom. Either way, I think I now know the real reason I was so strangely drawn to his photograph.

Truth, questioning, rights, courage, integrity: These were values my generation of Indians grew up to think were important. These were the values we believed Mohandas Gandhi stood for. They may belittle him today, but it is what we believed. And yet Gandhi was such an unusual man in every respect that he makes a difficult example for anyone to follow.

On Constitution Hill, Nagappen Padayachee seems easier to emulate. And so as he stands there, head tilted just so, I like to think: He stands for me.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)