Freedom from Ageism: Age no Bar is a Myth in India

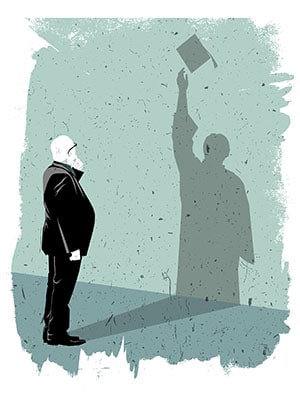

If the image of youth has changed rapidly in the recent past, then why hasn’t the image of our seniors?

Some years ago, I found myself scrambling for scholarships to pursue a master’s degree. At the age of 26, I realised that I was not eligible for most of them. I was too old. I also learnt that 26 was also too old to take up studying for a bachelor’s degree in engineering, law or medicine in our country. But when I did start a master’s course in the UK, I found in my class a man in his late 30s. “I am a mature student,” he had said. “I was not in a position to study when most youngsters do.”

The words ‘mature’ and ‘student’ do not go together in India: If you are one, you cannot possibly be the other.

I had not asked my classmate what his circumstances were. But it reminded me of the innumerable people in India who are in similar situations—or perhaps not, but simply want to study at an older age—and have no opportunity to do so. It brought back to mind my search for scholarships, and my growing indignation at being turned away because of my age. Exactly why should someone’s age have anything to do with the desire to gain knowledge?

If a person, of any age, wants to become, say, a doctor and begin a career much later than most others do, why should anyone thwart that desire? Especially the government?

By most measures, I am part of India’s famed ‘demographic dividend’: I fall between the 18 to 35 (or 20 to 45, or similar variations) age group that is the darling of marketers and advertisers, researchers and economists, employers and recruiters. The government is touting the likes of me as the future of the nation, while the rest of the world is looking on with a mix of growing concern and envy.

But must my life begin and end while I am in that age group?

Speaking to people who are in the business of hiring employees for client companies brings forth some more realities.

According to one HR manager, Indians are not comfortable being served food at restaurants, especially posh ones, by someone who is grey-haired. “It is alright if the chef is grey haired, the customer can’t see that,” he said. We also find it uncomfortable to have subordinates older than us: “An MD who is 45 would not want a manager who is 50. He feels uncomfortable,” the HR manager added.

Those who are older—and have families and responsibilities apart from the job—are reluctant to relocate, travel for ‘20 days a month’, and have ‘higher expectations’ from the company (read salary, leave). In short, said another HR manager, young employees are better suited for roles that require interaction with clients, and erratic and hectic work schedules, while older employees are better for consulting and training positions.

The manager also insisted that the age of an applicant for any job position is a critical factor: “Even if it is not mentioned in the CV, I will calculate it from the other details. And if not, then I will directly ask the person’s age.” That asking a job applicant’s age is illegal in the US and the UK holds little significance in India.

The average age of employees in a company is also determined, to some extent, by the age of the industry itself. So, IT (Infosys an exception) and telecom have younger people at the helm, while manufacturing, banking and FMCG have older CEOs. But younger industries have younger employees and CEOs largely because there is no older, more experienced talent available, not necessarily because they prefer younger people. This is corroborated by the fact that the average age of people on Business India’s 2011 survey of India’s Highest Paid Executives was 51. The survey (of executives earning more than Rs 50 lakh a year) also found the largest number of people in the 46-55 age group, and with work experience of 26 to 30 years. Definitely no brat pack.

We like to say we are a young country; we like to play the ‘demographic dividend’ card when everything else fails. Statistics do hold up the claim: 50 percent of our population is less than 25 years old; 65 percent is less than 35; we are younger than China, Brazil, Russia and the US. But we are also a country with severely entrenched notions of what one must do at a certain age. Perhaps the ancient Vedic philosophy of dividing life into four stages—Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha and Sanyas—has something to do with it, or perhaps the more recently entrenched practice of mandatory retirement.

Mandatory retirement is taken to be as much a fact of life as earning a livelihood. But, given the improving health and circumstances of our seniors, must it remain so? Mandatory retirement is unlawful in several countries—the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and Brazil—and employees are free to work for as long as they wish to. (There are exceptions for industries in which strict physical fitness levels are necessary.)

In India, however, retirement has been a government tool to ensure employment for the young. So, government employees must retire at 60, while private ones largely do so. This also ensures that while judges must retire, lawyers need not, and while bureaucrats retire, lawmakers—unsuprisingly—do not: 40- and 50-year-olds are considered young in politics, and parliamentarians in their 70s and 80s are more the norm than the exception.

In 2011, the department of personnel and training decided to keep the retirement age of government officials to 60, and not increase it to 62. A member of the Central government association had told the media: “The government is justified in not increasing the age as it will affect youngsters.”

But what of the fact that retirement from an active working life affects the mental and financial health of seniors? Gallup’s annual Economy and Personal Finance Survey of 2013 has found that Americans between 60 and 69 years of age who work have better emotional health than those who do not, and that financial concerns are a prime reason for the rise in the average retirement age. The survey found that the average non-retired American expects to retire at age 66, up from 60 in 1995 (37 percent said they expect to retire after 66; the number was 22 percent a decade ago, and 15 percent in 1995). The percentage of non-retirees who expect to retire before the age of 65 has declined from 49 in 1995 to 26 in 2013. Gallup attributes this to “changing norms about the value of work, the composition of the workforce, the decrease in jobs with mandatory retirement ages and other factors”.

Until the early 2000s—around the time the hype around young India’s growth began to rise—youth were considered energetic and enthusiastic, but also inexperienced and impulsive, while greying hair was associated with experience and wisdom, and also frailty. Now, older people are associated with redundancy. The image of youth has evolved rapidly in the recent past. But why hasn’t the image of seniors evolved as well? (This is at least one sphere in which our politicians are worthy examples.)

Maybe they could start with letting me become a doctor after I retire from being a journalist.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)