Feat of clay

Ceramics, long relegated to a lower status in the world of art, are gaining hard-earned ground at India's first ceramics triennale

Reyaz Badaruddin’s A Cup of Tea draws on memories of tea with friends

Reyaz Badaruddin’s A Cup of Tea draws on memories of tea with friendsPhotographs: Shine Bhola and Jawahar Kala Kendra

Earthenware, in the Indian subcontinent, dates back many thousand years to the Indus Valley civilisation. So abundant, ubiquitous and disposable has been the clay pot that rarely has it been considered to be anything special. And yet, when freed from the restraints of functionality, the humble earthenware can rise to the elevated heights of fine art.

Focusing a spotlight on this position that ceramics have achieved in India—thanks to artistes who have broken the mould that has defined their practice for centuries—is Breaking Ground, the first Indian Ceramics Triennale, on till November 18 at the Jawahar Kala Kendra (JKK) in Jaipur, in collaboration with the Contemporary Clay Foundation.

“Globally, there is a great understanding of Indian terracotta, but not of contemporary ceramics art,” says Anjani Khanna, director, Contemporary Clay Foundation. “The idea behind the triennale was to present ceramics in a different context; to show the achievements that have been made, and to push the boundaries of the practice.”

Rakhee Kane’s Shifting Identities draws inspiration from jaalis or screens

A recurring event of this scale—the first chapter of the triennale has 35 Indian and 12 international artiste projects, 10 collaborations, 12 speakers, a symposium, film screenings and workshops for adults and children—“is also the kind of platform that has the scope to engage and carry a lot of people with it,” she adds.

Pooja Sood, director general of JKK, says the venue is perfect for the country’s first triennale on ceramics. “Jaipur has always been associated with design and pottery, especially blue pottery,” she says, “while JKK has become a state-of-the-art gallery after undergoing a three-year renovation.”

The venue has made it possible for ceramic artistes, often restricted by space, to create works of art that would be difficult to display in regular galleries. “Ceramics are a medium, and the triennale has made it possible to showcase what all can be done with it, including performance arts and installations. Regular galleries are scared to show ceramics on a large scale for the simple reason that they might break. Some artistes have even created their artworks on-site.”

The limited scale, restrictions and display requirements are things Reyaz Badaruddin, a ceramic artiste and part of the six-member team that conceived the triennale, has experienced. “In other exhibitions and galleries, there have been restrictions such as excluding works that contain even a small portion of material that is strictly not ceramics,” he says. “There would be display requirements such as placing the artworks on pedestals.”

Ingrid Murphy’s dog has a QR code instead of a face

Ingrid Murphy’s dog has a QR code instead of a faceLimitations such as these would restrict artistes from pushing the boundaries of their creativity, which in turn meant ceramics would stay confined to the realm of making functional objects such as tableware, and variations thereof. Education, too, restricted ceramics to functional forms. “It was only after I studied for my masters degree at Cardiff School of Art & Design that my work changed a lot. Earlier, it was entirely functional; there was no story that I was telling, or comment that I was making. I never questioned myself, and asked why I was making what I was making,” says Badaruddin.

Badaruddin’s work at the triennale A Cup of Tea was created to celebrate the 70th birthday of Ray Meeker, the celebrated co-founder of Golden Bridge Pottery, who moved from the US to Puducherry in 1970. “We would always meet over tea, and the artwork brings together memories and friendships,” says Badaruddin. In addition to his own collection, he asked 14 other ceramicists to make a cup for him. Each cup is unique, and together they tell stories of shared moments, past, present and future.

Moving into layers that don’t always immediately meet the eye is ceramicist Vineet Kacker, also a member of the team behind conceiving the triennale. Most of his works, inspired by the landscapes and iconography of the Himalayas and Eastern spirituality, can be viewed at various levels, with the deeper layers raising questions within the viewer. While his abstract works draw inspiration from a sense of self, he also invests the clay—“a material that has an immediacy that is very seductive,” he says—with acts of writing and stamping, all of which help communicate with the viewer.

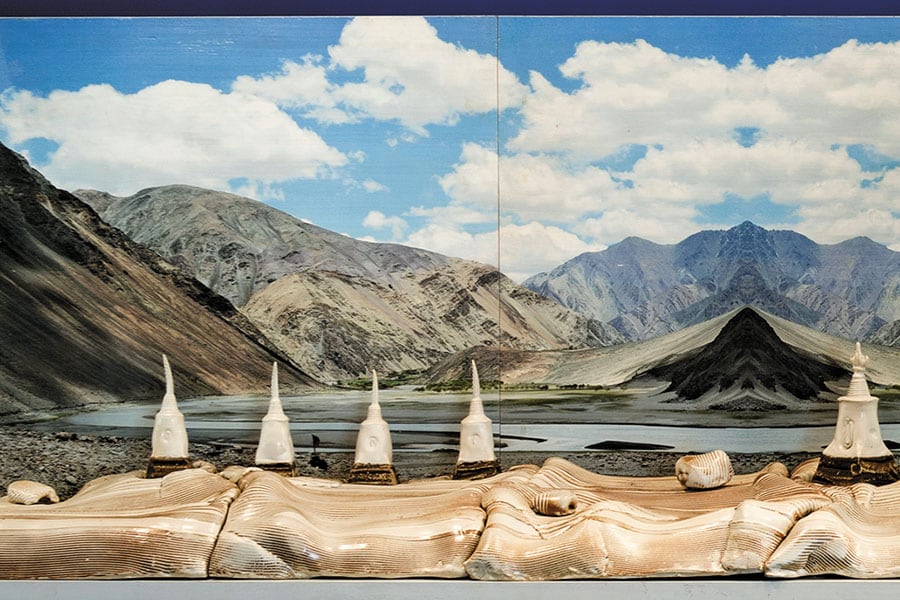

Vineet Kacker’s work Endless Landscapes includes ceramics and photographs

Vineet Kacker’s work Endless Landscapes includes ceramics and photographs“In our culture, we fall to believing in certain iconography very directly,” says Kacker. “Rarely do we engage with what it really stands for. We don’t ask why these things are being treated as a sacred object. My works are more about leading the viewer into deeper questions.” For instance, his ‘vish/amrit’ teapot has two spouts, indicating that both energies—negative and positive—are possible, and can manifest into opposites.

Kacker’s work at the triennale, called Endless Landscapes, includes ceramics and photographs, and uses mirrors to reflect the tableaux in an infinite way. “It echoes the endlessness of the Himalayas, and draws the viewer into becoming a part of the landscape.”

Kacker believes that the very fact that the triennale has taken shape is indication of the fact that ceramic art has reached a certain level of maturity in the country, with a diversity in the way artistes are using the medium. “It throws open doors to what is possible with the medium,” he says. “With technology, today, the most basic of materials can lend itself to challenge the notions we have of it.” He highlights the use of technology with the example of an artwork by Ingrid Murphy from the UK. A dog by Murphy, a replica of decorative porcelain dogs once popular in the UK, has a QR code instead of a face. Viewers can scan the code on their smartphones and access an online archive of photographs of porcelain dogs sitting on mantles across various geographies.

Badaruddin says that although pottery is very old in India, ceramics as an art form is very new. “There are very few art schools that teach ceramics, and there aren’t many artistes practising seriously. However, in the recent past, people have been going abroad, and there is a lot of exposure to what is happening in other places,” he says.

The triennale is also a reflection of the fact that globally ceramics are witnessing a resurgence. Highlighting this was the presence of British ceramicist Kate Malone, who was one of the judges of BBC television programme The Great Pottery Throwdown. Malone, along with three of her assistants, recreated her studio at the triennale for 10 days to replicating its ethos and atmosphere.

Khanna, of the Contemporary Clay Foundation, says that while in countries such as Japan and China, ceramics and porcelain were elevated to a position of fine art, thanks to their Zen traditions and tea drinking ceremonies, in India the potter has had an ambiguous position in society. While he is a creator, what he creates is considered to be rather cheap and abundant, and, therefore, less prized. Materials like metals, because of their relative rarity, difficulty of excavation and purification, and consequent cost, have been more valued.

Within the world of art, too, ceramics and ceramicists have been pretty much left to themselves, with very few curators seeking them out for shows and exhibitions. However, she points to rather practical reasons why ceramics have seen a surge in the recent past. “Artistes have been able to establish their studios much more easily than in the past, often because it is simply much easier to have a kiln,” she says. “It took me 10 years to set up my studio in Alibaug after I bought land there in 1999.” Today, artistes have the options of buying kilns, importing them or getting someone to make one for them. Even factors such as improved packaging and transporting infrastructure and support means artistes are able to showcase their works in different places more easily now than in the past.

“As artistes we were never really encouraged,” says Badaruddin. “We had only always dreamt of doing something on this scale.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X