A Night At The Taj

How seven South African security consultants saved the lives of fellow guests when terrorists struck

PRELUDE

It was near sunset on November 26, 2008. Somewhere off the west coast of Mumbai, a group of young men were waiting for darkness, in a boat without lights, waiting so they could land, unobserved, at a fishing village near the southern tip of the elongated island city.

Captain Ravi Dharnidharka gazed out over the fishermen’s huts lining the Arabian Sea coast. A US Marine of Indian descent, he had family in Mumbai. In India after 13 years, he was on holiday, staying with cousins near Badhwar Park, close to tony Cuffe Parade. His extended family — uncles and more cousins — decided to meet for dinner at Souk, the Lebanese restaurant on the 20th floor of the Taj Mahal Palace.

Dhanesh Mehta, businessman, was in the Taj lobby with his wife, Shruti, and their daughter Shivani, deciding on which restaurant to go to. It was Shivani’s birthday the next day, so she got to pick. She wanted Lebanese food. So, Souk it was.

Anand Parekh and his family — wife Jamini, son Anirrudh, and mother, Rama — were meeting Anand’s brother, Apurva, his wife Kalpana, and their children around 10 pm for dinner. They voted for Wasabi but Apurva’s daughter nixed it, because she’d lunched there that afternoon. They decided on Souk instead.

Robert Nicholls and Faisul had had a long day. Several long days, actually. They worked for Nicholls-Steyn and Associates, a South African security firm hired by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) for the Champions League T20 tournament. After meetings at the BCCI office, they were back at the Taj, where they were staying.

Shortly, Zane Wilmans, Reagan Walters, Reuben Neikerk, Charles Shiffier and Zunaid Wadee trooped in. Rugged, tough ex-commandos all, their 90-minute ride from the airport had taken as much of a toll on them as the 10-hour flight from Johannesburg, South Africa.

After the new arrivals had checked in and freshened up, they met for dinner. They were in the mood for Chinese food, but the Golden Dragon was full. The only restaurant with enough space for them was Souk.

DINNER

Around 9 p.m., the Mehtas sat down to order. Their hummus and pita took some time to arrive. As they began eating, their driver called to ask if they were alright. They said they were fine. But why was he asking? He said he had heard gunfire. Dhanesh told him not to worry. He told Shruti, “I think there’s some sort of gang war going on downstairs. By the time we are done, hopefully it should be over.”

Dharnidharka and his family were a few tables away from the Mehtas. The Marine was on edge; his instincts told him something wasn’t right. The number of phones, for instance, that were ringing. And the staff seemed on tenterhooks. Then his cousins got calls from friends; something about shootouts in Colaba. He heard gunshots, but didn’t know what to make of it. Then an aunt called, saying she’d heard there was a crazy man outside the Taj waving a gun in the air.

Most of the Parekhs had assembled inside Souk, from where they heard muffled sounds but dismissed them as one of the usual city disturbances. At around 10 p.m., they got a call from Apurva’s daughter, who said the hotel’s security men weren’t letting them come up because there was some shooting inside the hotel. When the Parekhs asked the Souk staff, they were told that there was a gang war going on downstairs. They assumed it would soon be sorted out.

The South Africans (we’ll call them the Seven, for short) had settled at a table, ordered kebabs, some starters and beer, and were discussing their assignment.

Around 9.30 p.m., they heard an explosion. They assumed it was just another noisy celebration. But, five minutes later, they heard a louder one and it felt like it came from inside the hotel. One of them went to the window and looked down: Everything seemed normal.

A little later, Wilmans got up to use the restroom outside the restaurant, but the staff wouldn’t let him out. One of the staff members said, “I’m sorry sir, but you can’t go right now. We have been given instructions that no one can leave the restaurant.” When Wilmans asked why, he was told there were two men in the lobby shooting at each other, but it should be sorted out pretty soon. Being from South Africa, where violent crime isn’t unusual, he accepted the explanation. Back at the table, his mates were similarly philosophical when he told them what had happened.

Then there was a much bigger and louder explosion. Now, they knew it was inside the hotel. The Seven got on their phones and began calling their Mumbai contacts, the police, the media and other team members. They talked to the staff and other guests at the restaurant, piecing the situation together. The conclusion was grim: Men with guns were inside the hotel, shooting. Sources in the police told them gunmen had attacked and killed people in other parts of the city.

DEFENSIVE MANOEUVERS

The Seven decided to take charge. They realised they were in the middle of something big and were dealing with terrorists and that they were probably the only ones in the room equipped to deal with the situation. Tall, combat-hardened, built like battle-tanks, they were a formidable force. They called a council of war.

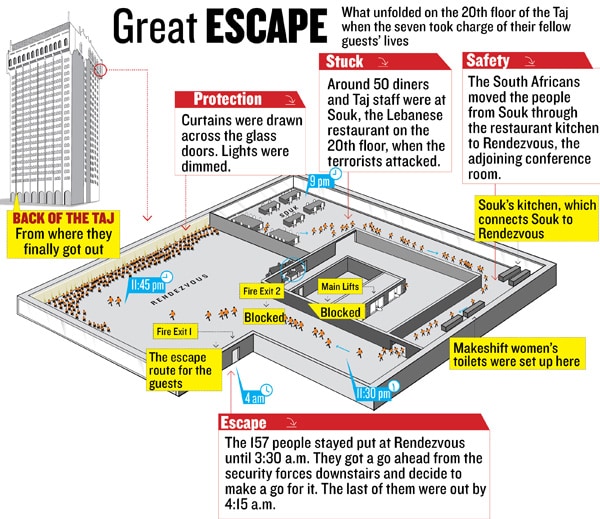

First, information, which they were getting from the outside world and the hotel staff. Next, risk assessment and defense resources: The immediate danger was Souk’s glass doors. Terrorists coming up wouldn’t even have to get in; a single grenade and the shattering glass would cause carnage.

Wilmans and Nicholls explained the situation to the people at Souk, told them who they were, and that they would make sure everyone got out safely. Their first order was for everyone to move to the back of the restaurant, as far away from the glass doors as possible.

Wilmans remembered there was another door next to the restaurant. The Souk staff said it was a conference room, Rendezvous. He went through the kitchen and looked in, to find 100 very confused and worried Koreans. The room was large and it could take in the extra 50-odd people from Souk. And, reassuringly, it had huge, thick, wooden double-doors.

Wilmans went back to his colleagues and they decided it would be safest to move everyone there. Dharnidharka, understanding that the Seven seemed to know what they were doing, went over to Wilmans and introduced himself. Wilmans got him to Nicholls and introduced the two.

Dharnidharka and Nicholls did a recce: There were two fire stairways they could use, one outside and the other inside the conference hall. They blocked the outside one with tables, chairs and anything else they could find, to make it as difficult as possible for the terrorists to come up.

Meanwhile, the Taj staff went to work, calming the guests and making sure no one panicked. They put stoppers between the lift doors, ensuring the terrorists couldn’t use them to come up.

One woman’s husband was part of Taj’s security system. She was constantly on the phone with him, relaying information to the Seven.

Most of the diners were very calm; some hadn’t grasped what was going on.

The Seven quickly moved everyone through the kitchen into Rendezvous. En route, they stopped to arm themselves with whatever they could — knives, meat cleavers, rods, anything that could be used as a weapon — and tucked them into their waistbands, pulling their shirts over them to conceal them. Kitchen tools could hardly stop AK-47-wielding terrorists, they knew, but they were counting on the terrorists not expecting resistance.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Next step: Reassure the Koreans. Wilmans turned to Nicholls and said, “We got to tell these guys who we are and what we are planning to do. We were 50 before and now we’ve added 100.” Nicholls agreed and walked up to the microphone set up for the speakers, from where he briefed everyone. The quiet confidence of the Seven calmed everyone. Except for one ex-armyman, who wanted to take charge. Wilmans asked him to be quiet. Wilmans is 6’1” and weighs 110 kg. The armyman subsided.

Then, the Seven began to secure the place: Curtains to the many windows facing outside were drawn, lights were dimmed, the doors were wrapped shut with wire and barricaded with every available heavy object.

Instructions were given: “Don’t talk loudly on the phone. Don’t tell people where we are. Keep close to the floor. Don’t move around. Don’t sit under the chandeliers.”

Any word that got out could mean the terrorists would know; they would be 157 sitting ducks. That was probably one of their wisest decisions: The media outside were in a frenzy, reporting every little detail they could get their hands on.

Wilmans and Dharnidharka barricaded the fire escape inside Rendezvous and posted a couple of the Taj staff there so that, at a signal, they could start unblocking the stairs if they had to make a quick exit.

THE WAIT

Time passed. The Taj staff made sure service was still on. Water, food, tea, coffee were available to anyone who asked.

Shivani Mehta’s phone refused to stop ringing, with friends calling to wish her a happy birthday. Her elder sister, Shaili, a student in the USA, was one of the first to call. When she heard that her family was trapped in the Taj, Shaili broke down. Shivani passed the phone to her mother Shruti, who broke down as well. Dhanesh walked over to the food counter and broke off half a pastry and came back to his wife and daughter. “Happy birthday,” he told Shivani.

“Papa, at this time?”

He smiled and fed her some pastry.

Then there were two huge explosions. The terrorists had set off RDX in the heritage towers of the Taj. The impact was felt all the way up on the 20th floor.

People huddled together on the floor. A few sobbed silently. Most were too shocked to react. The Seven kept watch. Whenever they felt that someone was losing their nerve, one of them would go and talk to them. Hysteria in a situation like this would be contagious. If the Seven were worried themselves, they took care not to show it. Their air of confidence rubbed off on the others. The worst that happened was a woman fainting.

Some time later, a few of the women told Nicholls they really needed to use the restroom. Nicholls asked his men to unblock the door and recce the outside area. He told the women that his men would escort them to and fro. But, as they stepped out, another huge explosion from far below sent tremors through the floor. The women decided that restrooms weren’t a priority after all.

The Souk staff and the Seven soon found a solution to the problem. They improvised bathrooms for the women in the washing area of Souk by removing the drain covers and putting overturned crates over them. For the men, they set up huge pails of ice at the far end of Rendezvous, behind a screen.

Tension continued to build. A couple of blasts that shook the room were particularly bad. Nicholls calmly lied: “That’s the police making their entry into the hotel.”

He gave everyone paper, asked them to write their names and addresses, saying this was to follow up later and make sure everyone was safe. Again, not quite the truth. They had no way of following up with everyone. But they had to give them something to do.

ESCAPE

Around 2 a.m., the terrorists set off 10 kg of RDX below the central dome of the Taj; they also set fire to the sixth floor of the hotel. Nicholls could see the flames raging.

Rumours kept coming in about police and other forces mounting rescue missions for the people at Rendezvous. But they knew that the fighting was too intense for any operation to start. They were told it would be best if they stayed put.

But the fire changed everything.

If it spread from the hotel’s old wing, they would have a whole new set of problems to deal with. The fire would spread upwards, blocking exits. Even if the fire did not spread, there were chances of short-circuiting and the power going off.

Best to get out now, they told Taj security. In a little while, they heard noises coming up from the fire exit. Men from the security force were coming to escort them out. Nicholls sent a couple of his men down to make sure the path was clear. Wilmans, Dharnidharka and a couple of the hotel staff cleared the barricades from the escape route.

The recce party came back and said the way was clear. Instructions were issued: Phones off, shoes off; the exodus would have to be as noiseless as possible. As they prepared to leave, they realised that the Parekhs had a crisis: 84-year-old Rama would not be able to manage 20 flights of stairs. She insisted on being left behind, which, obviously, was not an option.

Dharnidharka volunteered to carry her downstairs. The stairwell was too narrow for her to be carried down in a chair. Dharnidharka and a waiter carried her in their arms, a third person supported her back. It wasn’t easy on the woman either, but she never complained.

The group moved slowly. First went a couple of the South Africans and Taj security men, then the women and children, then more security men, and lastly the men.

The tricky part was at each landing. Every floor has a fire exit with a glass panel from where one could see the floor’s lobby. Every landing had to be crossed really carefully.

When all of them got to the lobby level, they found that the way out to the street was still under fire. They had to move to the next exit. There, no one wanted to be the first to run out. What if the terrorists saw them? Shruti Mehta had had enough. She grabbed her daughter’s hand and ran out. They kept running till they reached the safe area near the Gateway of India, where the media and police were.

A few minutes later, they were all out of the hotel. The ordeal was over.

Zane Wilmans noticed something that made him smile: All the Koreans were still immaculate — not even their ties were loosened — and they were still holding on to their convention gift bags.

(This narrative was put together from conversations with Zane Wilmans, Robert Nicholls, Ravi Dharnidharka, Anand Parekh and Danesh Mehta. The staff of Taj Mahal Hotel did not participate in this story; the hotel’s management has decided to put the event behind them. The Korean embassy did not comment)

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

Zane Wilmans: Left Nicholls-Steyn and Associates (NSA) to start Protexx Security in India. He’s married to an Indian and loves the country. He goes back to the Taj and Souk as often as he can.

Bob Nicholls: Still runs NSA in South Africa.

Ravi Dharnidharka: Works in the aftermath business development department for Goodrich Industries in California. He is a reserve officer in the US Marine Corps.

The Parekhs: Anand and Anirrudh run their business out of Maker Chambers, in Nariman Point. They were at the re-opening ceremony of the Taj and the Souk.

The Mehtas: Shruti suffered post traumatic stress and didn’t get out of bed for three days after the attacks. Later, the family went to the Taj as a show of faith. Shivani is studying psychology at Sarah Lawrence University, New York.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)